The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language (57 page)

Read The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language Online

Authors: Steven Pinker

To arrive at their vocabulary counts in the hundreds, the investigators would also “translate” the chimps’ pointing as a sign for

you

, their hugging as a sign for

hug

, their picking, tickling, and kissing as signs for

pick, tickle

, and

kiss

. Often the same movement would be credited to the chimps as different “words,” depending on what the observers thought the appropriate word would be in the context. In the experiments in which the chimps interacted with a computer console, the key that the chimp had to press to initialize the computer was translated as the word

please

. Petitto estimates that with more standard criteria the true vocabulary count would be closer to 25 than 125.

Actually, what the chimps were really doing was more interesting than what they were claimed to be doing. Jane Goodall, visiting the project, remarked to Terrace and Petitto that every one of Nim’s so-called signs was familiar to her from her observations of chimps in the wild. The chimps were relying heavily on the gestures in their natural repertoire, rather than learning true arbitrary ASL signs with their combinatorial phonological structure of hand shapes, motions, locations, and orientations. Such backsliding is common when humans train animals. Two enterprising students of B. F. Skinner, Keller and Marian Breland, took his principles for shaping the behavior of rats and pigeons with schedules of reward and turned them into a lucrative career of training circus animals. They recounted their experiences in a famous article called “The Misbehavior of Organisms,” a play on Skinner’s book

The Behavior of Organisms

. In some of their acts the animals were trained to insert poker chips in little juke boxes and vending machines for a food reward. Though the training schedules were the same for the various animals, their species-specific instincts bled through. The chickens spontaneously pecked at the chips, the pigs tossed and rooted them with their snouts, and the raccoons rubbed and washed them.

The chimp’s abilities at anything one would want to call grammar were next to nil. Signs were not coordinated into the well-defined motion contours of ASL and were not inflected for aspect, agreement, and so on—a striking omission, since inflection is the primary means in ASL of conveying who did what to whom and many other kinds of information. The trainers frequently claim that the chimps have syntax, because pairs of signs are sometimes placed in one order more often than chance would predict, and because the brighter chimps can act out sequences like

Would you please carry the cooler to Penny

. But remember from the Loebner Prize competition (for the most convincing computer simulation of a conversational partner) how easy it is to fool people into thinking that their interlocutors have humanlike talents. To understand the request, the chimp could ignore the symbols

would, you, please, carry, the

, and

to;

all the chimp had to notice was the order of the two nouns (and in most of the tests, not even that, because it is more natural to carry a cooler to a person than a person to a cooler). True, some of the chimps can carry out these commands more reliably than a two-year-old child, but this says more about temperament than about grammar: the chimps are highly trained animal acts, and a two-year-old is a two-year-old.

As far as spontaneous output is concerned, there is no comparison. Over several years of intensive training, the average length of the chimps’ “sentences” remains constant. With nothing more than exposure to speakers, the average length of a child’s sentences shoots off like a rocket. Recall that typical sentences from a two-year-old child are

Look at that train Ursula brought

and

We going turn light on so you can’t see

. Typical sentences from a language-trained chimp are:

Nim eat Nim eat.

Drink eat me Nim.

Me gum me gum.

Tickle me Nim play.

Me eat me eat.

Me banana you banana me you give.

You me banana me banana you.

Banana me me me eat.

Give orange me give eat orange me eat orange give me eat orange give me you.

These jumbles bear scant resemblance to children’s sentences. (By watching long enough, of course, one is bound to find random combinations in the chimps’ gesturing that can be given sensible interpretations, like

water bird

). But the strings

do

resemble animal behavior in the wild. The zoologist E. O. Wilson, summing up a survey of animal communication, remarked on its most striking property: animals, he said, are “repetitious to the point of inanity.”

Even putting aside vocabulary, phonology, morphology, and syntax, what impresses one the most about chimpanzee signing is that fundamentally, deep down, chimps just don’t “get it.” They know that the trainers like them to sign and that signing often gets them what they want, but they never seem to feel in their bones what language is and how to use it. They do not take turns in conversation but instead blithely sign simultaneously with their partner, frequently off to the side or under a table rather than in the standardized signing space in front of the body. (Chimps also like to sign with their feet, but no one blames them for taking advantage of this anatomical gift.) The chimps seldom sign spontaneously; they have to be molded, drilled, and coerced. Many of their “sentences,” especially the ones showing systematic ordering, are direct imitations of what the trainer has just signed, or minor variants of a small number of formulas that they have been trained on thousands of times. They do not even clearly get the idea that a particular sign might refer to a kind of object. Most of the chimps’ object signs can refer to any aspect of the situation with which an object is typically associated.

Toothbrush

can mean “toothbrush,” “toothpaste,” “brushing teeth,” “I want my toothbrush,” or “It’s time for bed.”

Juice

can mean “juice,” “where juice is usually kept,” or “Take me to where the juice is kept.” Recall from Ellen Markman’s experiments in Chapter 5 that children use these “thematic” associations when sorting pictures into groups, but they ignore them when learning word meanings: to them, a

dax

is a dog or another dog, not a dog or its bone. Also, the chimps rarely make statements that comment on interesting objects or actions; virtually all their signs are demands for something they want, usually food or tickling. I cannot help but think of a moment with my two-year-old niece Eva that captures how different are the minds of child and chimp. One night the family was driving on an expressway, and when the adult conversation died down, a tiny voice from the back seat said, “Pink.” I followed her gaze, and on the horizon several miles away I could make out a pink neon sign. She was commenting on its color, just for the sake of commenting on its color.'

Within the field of psychology, most of the ambitious claims about chimpanzee language are a thing of the past. Nim’s trainer Herbert Terrace, as mentioned, turned from enthusiast to whistle-blower. David Premack, Sarah’s trainer, does not claim that what she acquired is comparable to human language; he uses the symbol system as a tool to do chimpanzee cognitive psychology. The Gardners and Patterson have distanced themselves from the community of scientific discourse for over a decade. Only one team is currently making claims about language. Sue Savage-Rumbaugh and Duane Rumbaugh concede that the chimps they trained at the computer console did not learn much. But they are now claiming that a different variety of chimpanzee does much better. Chimpanzees come from some half a dozen mutually isolated “islands” of forest in the west African continent, and the groups have diverged over the past million years to the point where some of the groups are sometimes classified as belonging to different species. Most of the trained chimps were “common chimps”; Kanzi is a “pygmy chimp” or “bonobo,” and he learned to bang on visual symbols on a portable tablet. Kanzi, says Savage-Rumbaugh, does substantially better at learning symbols (and at understanding spoken language) than common chimps. Why he would be expected to do so much better than members of his sibling species is not clear; contrary to some reports in the press, pygmy chimps are no more closely related to humans than common chimps are. Kanzi is said to have learned his graphic symbols without having been laboriously trained on them—but he was at his mother’s side watching while

she

was laboriously trained on them (unsuccessfully). He is said to use the symbols for purposes other than requesting—but at best only four percent of the time. He is said to use three-symbol “sentences”—but they are really fixed formulas with no internal structure and are not even three symbols long. The so-called sentences are all chains like the symbol for chase followed by the symbol for hide followed by a point to the person Kanzi wants to do the chasing and hiding. Kanzi’s language abilities, if one is being charitable, are above those of his common cousins by a just-noticeable difference, but no more.

What an irony it is that the supposed attempt to bring

Homo sapiens

down a few notches in the natural order has taken the form of us humans hectoring another species into emulating our instinctive form of communication, or some artificial form we have invented, as if that were the measure of biological worth. The chimpanzees’ resistance is no shame on them; a human would surely do no better if trained to hoot and shriek like a chimp, a symmetrical project that makes about as much scientific sense. In fact, the idea that some species needs our intervention before its members can display a useful skill, like some bird that could not fly until given a human education, is far from humble!

So human language differs dramatically from natural and artificial animal communication. What of it? Some people, recalling Darwin’s insistence on the gradualness of evolutionary change, seem to believe that a detailed examination of chimps’ behavior is unnecessary: they must have some form of language, as a matter of principle. Elizabeth Bates, a vociferous critic of Chomskyan approaches to language, writes:

If the basic structural principles of language cannot be learned (bottom up) or derived (top down), there are only two possible explanations for their existence: either Universal Grammar was endowed to us directly by the Creator, or else our species has undergone a mutation of unprecedented magnitude, a cognitive equivalent of the Big Bang…. We have to abandon any strong version of the discontinuity claim that has characterized generative grammar for thirty years. We have to find some way to ground symbols and syntax in the mental material that we share with other species.

But, in fact, if human language is unique in the modern animal kingdom, as it appears to be, the implications for a Darwinian account of its evolution would be as follows: none. A language instinct unique to modern humans poses no more of a paradox than a trunk unique to modern elephants. No contradiction, no Creator, no big bang.

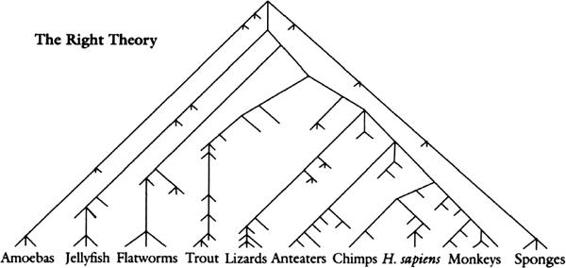

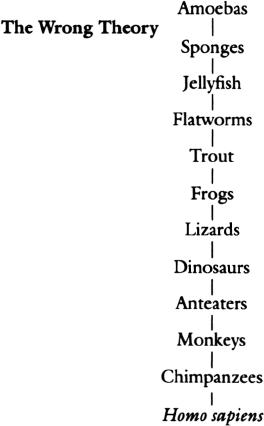

Modern evolutionary biologists are alternately amused and annoyed by a curious fact. Though most educated people profess to believe in Darwin’s theory, what they really believe in is a modified version of the ancient theological notion of the Great Chain of Being: that all species are arrayed in a linear hierarchy with humans at the top. Darwin’s contribution, according to this belief, was showing that each species on the ladder evolved from the species one rang down, instead of being allotted its rang by God. Dimly remembering their high school biology classes that took them on a tour of the phyla from “primitive” to “modern,” people think roughly as follows: amoebas begat sponges which begat jellyfish which begat flatworms which begat trout which begat frogs which begat lizards which begat dinosaurs which begat anteaters which begat monkeys which begat chimpanzees which begat us. (I have skipped a few steps for the sake of brevity.)

Hence the paradox: humans enjoy language while their neighbors on the adjacent rung have nothing of the kind. We expect a fade-in, but we see a big bang.

But evolution did not make a ladder; it made a bush. We did not evolve from chimpanzees. We and chimpanzees evolved from a common ancestor, now extinct. The human-chimp ancestor evolved not from monkeys but from an even older ancestor of the two, also extinct. And so on, back to our single-celled forebears. Paleontologists like to say that to a first approximation, all species are extinct (ninety-nine percent is the usual estimate). The organisms we see around us are distant cousins, not great-grandparents; they are a few scattered twig-tips of an enormous tree whose branches and trunk are no longer with us. Simplifying a lot: