The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language (15 page)

Read The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language Online

Authors: Steven Pinker

There is another reason to believe that a sentence is held together by a mental tree. So far I have been talking about stringing words into a grammatical order, ignoring what they mean. But grouping words into phrases is also necessary to connect grammatical sentences with their proper meanings, chunks of mentalese. We know that the sentence shown above is about a girl, not a boy, eating ice cream, and a boy, not a girl, eating hot dogs, and we know that the boy’s snack is contingent on the girl’s, not vice versa. That is because

girl

and

ice cream

are connected inside their own phrase, as are

boy

and

hot dogs

, as are the two sentences involving the girl. With a chaining device it’s just one damn word after another, but with a phrase structure grammar the connectedness of words in the tree reflects the relatedness of ideas in mentalese. Phrase structure, then, is one solution to the engineering problem of taking an interconnected web of thoughts in the mind and encoding them as a string of words that must be uttered, one at a time, by the mouth.

One way to see how invisible phrase structure determines meaning is to recall one of the reasons mentioned in Chapter 3 that language and thought have to be different: a particular stretch of language can correspond to two distinct thoughts. I showed you examples like

Child’s Stool Is Great for Use in Garden

, where the single word

stool

has two meanings, corresponding to two entries in the mental dictionary. But sometimes a whole sentence has two meanings, even if each individual word has only one meaning. In the movie

Animal Crackers

, Groucho Marx says, “I once shot an elephant in my pajamas. How he got into my pajamas I’ll never know.” Here are some similar ambiguities that accidentally appeared in newspapers:

Yoko Ono will talk about her husband John Lennon who was killed in an interview with Barbara Walkers.

Two cars were reported stolen by the Groveton police yesterday.

The license fee for altered dogs with a certificate will be $3 and for pets owned by senior citizens who have not been altered the fee will be $1.50.

Tonight’s program discusses stress, exercise, nutrition, and sex with Celtic forward Scott Wedman, Dr. Ruth Westheimer, and Dick Cavett.

We will sell gasoline to anyone in a glass container.

For sale: Mixing bowl set designed to please a cook with round bottom for efficient beating.

The two meanings in each sentence come from the different ways in which the words can be joined up in a tree. For example, in

discuss sex with Dick Cavett

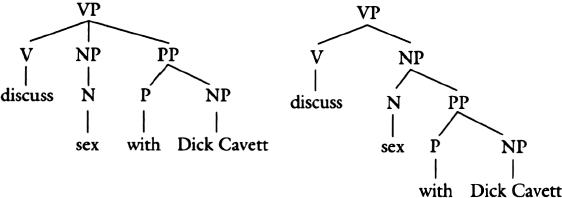

, the writer put the words together according to the tree below (“PP” means prepositional phrase): sex is what is to be discussed, and it is to be discussed with Dick Cavett.

The alternative meaning comes from our analyzing the words according to the tree at the right: the words

sex with Dick Cavett

form a single branch of the tree, and sex with Dick Cavett is what is to be discussed.

Phrase structure, clearly, is the kind of stuff language is made of. But what I have shown you is just a toy. In the rest of this chapter I will try to explain the modern Chomskyan theory of how language works. Chomsky’s writing are “classics” in Mark Twain’s sense: something that everybody wants to have read and nobody wants to read. When I come across one of the countless popular books on mind, language, and human nature that refer to “Chomsky’s deep structure of meaning common to all human languages” (wrong in two ways, we shall see), I know that Chomsky’s books of the last twenty-five years are sitting on a high shelf in the author’s study, their spines uncracked, their folios uncut. Many people want to have a go at speculating about the mind but have the same impatience about mastering the details of how language works that Eliza Doolittle showed to Henry Higgins in

Pygmalion

when she complained, “I don’t want to talk grammar. I want to talk like a lady in a flower shop.”

For nonspecialists the reaction is even more extreme. In Shakespeare’s

The Second Part of King Henry VI

, the rebel Dick the Butcher speaks the well-known line “The first thing we do, let’s kill all the lawyers.” Less well known is the second thing Dick suggests they do: behead Lord Say. Why? Here is the indictment presented by the mob’s leader, Jack Cade:

Thou hast most traitorously corrupted the youth of the realm in erecting a grammar school…. It will be proved to thy face that thou hast men about thee that usually talk of a noun and a verb, and such abominable words as no Christian ear can endure to hear.

And who can blame the grammarphobe, when a typical passage from one of Chomsky’s technical works reads as follows?

To summarize, we have been led to the following conclusions, on the assumption that the trace of a zero-level category must be properly governed. 1. VP is

>-marked by I. 2. Only lexical categories are L-markers, so that VP is not L-marked by I. 3.

-government is restricted to sisterhood without the qualification (35). 4. Only the terminus of an X

0

-chain can-mark or Case-mark. 5. Head-to-head movement forms an A-chain. 6. SPEC-head agreement and chains involve the same indexing. 7. Chain coindexing holds of the links of an extended chain. 8. There is no accidental coindexing of I. 9. I-V coindexing is a form of head-head agreement; if it is restricted to aspectual verbs, then base-generated structures of the form (174) count as adjunction structures. 10. Possibly, a verb does not properly govern its

-marked complement.

All this is unfortunate. People, especially those who hold forth on the nature of mind, should be just plain curious about the code that the human species uses to speak and understand. In return, the scholars who study language for a living should see that such curiosity can be satisfied. Chomsky’s theory need not be treated by either group as a set of cabalistic incantations that only the initiated can mutter. It is a set of discoveries about the design of language that can be appreciated intuitively if one first understands the problems to which the theory provides solutions. In fact, grasping grammatical theory provides an intellectual pleasure that is rare in the social sciences. When I entered high school in the late 1960s and electives were chosen for their “relevance,” Latin underwent a steep decline in popularity (thanks to students like me, I confess). Our Latin teacher Mrs. Rillie, whose merry birthday parties for Rome failed to slow the decline, tried to persuade us that Latin grammar honed the mind with its demands for precision, logic, and consistency. (Nowadays, such arguments are more likely to come from the computer programming teachers.) Mrs. Rillie had a point, but Latin declensional paradigms are not the best way to convey the inherent beauty of grammar. The insights behind Universal Grammar are much more interesting, not only because they are more general and elegant but because they are about living minds rather than dead tongues.

Let’s start with nouns and verbs. Your grammar teacher may have had you memorize some formula that equated parts of speech with kinds of meanings, like

A

NOUN

’s the name of any thing;As school or garden, hoop

or

swing

.V

ERBS

tell of something being done;To

read, count, sing, laugh, jump

, or

run

.

But as in most matters about language, she did not get it quite right. It is true that most names for persons, places, and things arc nouns, but it is not true that most nouns are names for persons, places, or things. There are nouns with all kinds of meanings:

the

destruction

of the city [an action]the

way

to San Jose [a path]whiteness

moves downward [a quality]three

miles

along the path [a measurement in space]It takes three

hours

to solve the problem. [a measurement in time]Tell me the

answer

. [“what the answer is,” a question]She is a

fool

. [a category or kind]a meeting

[an event]the

square root

of minus two [an abstract concept]He finally kicked

the bucket

. [no meaning at all]

Likewise, though words for things being done, such as

count

and

jump

, are usually verbs, verbs can be other things, like mental states (

know, like

), possession (

own, have

), and abstract relations among ideas

(falsify, prove)

.