The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (38 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

In these wretched conditions, both Muhammad’s wife Khadija and his uncle Abu Talib grew ill and died. And it was in these wretched conditions that Muhammad was given a new revelation: God permitted those who were wronged and driven from their homes to fight back.

14

Outside of Mecca, it was slightly easier to be known as a follower of Muhammad. The tribes of Medina were looking for a solution to the unrest and intertribal warfare in their own city; having heard Muhammad’s message from refugees who had fled Mecca for the more welcoming streets of Medina, a delegation came to visit the prophet and listen to what he had to say. Some were converted; Muhammad called these converts

Ansar

, “Helpers,” a name that was often given afterwards to the followers of Allah who were not from the city of Mecca and not part of Muhammad’s own tribe.

Muhammad, who believed that he had not yet been given divine permission to leave the city of his birth, remained in Mecca long after almost all of his followers had fled. Their departure put him in a much more dangerous position; he had little support left in the city, and the revelation allowing his followers to fight back against their oppressors had made the clan leaders of the Quraysh more suspicious of him than before. “When the Quraysh saw that the prophet had a party and companions not of their tribe and outside their territory,” Ishaq writes, “they feared that the prophet might join them, since they knew he had decided to fight them.”

15

So the Quraysh planned that one representative of each clan would join in a group assassination of Muhammad. That way, no single family would bear responsibility for his death. “It was then,” Ishaq concludes, “that God gave permission to his prophet to migrate.”

Only Muhammad’s cousin Ali and his old friend Abu Bakr were left with him in Mecca. Under cover of dark, Abu Bakr and Muhammad climbed out of the back window of Abu Bakr’s house (which was being watched) and made for Medina, while Ali stayed behind to make sure that all the prophet’s debts were settled. The day of his flight, the Hijra, was September 24, 622. Afterwards, all dates for the followers of Muhammad—now known as Muslims—were counted as “after the Hijra.”

*

The Hijra was the first day of the first year of a new way of reckoning. This, not the date of Muhammad’s first vision, was the point at which Muslims reckoned that their identity began. It was only when Muhammad came to Medina that he was able to begin to shape his followers into something new. Like Constantine, he had discovered a bond that could hold together a group of Arabs who did not naturally count themselves as members of one clan, or one city, or one nation. This bond of belief—belief in the one Creator, commitment to a life of justice and purity in His name—had created a new kind of tribe. All those who followed the words of Muhammad were

umma,

“one community to the exclusion of all men.”

16

The

umma

were by far the most powerful group in Medina, and as their leader, Muhammad was the de facto ruler of the city. But not all of the residents of Medina were members of the

umma

; some of the Arabs and all of the Jews held themselves apart. One of Muhammad’s first concerns was to protect their rights. He did not want to re-create the stratified system of his home city, with members of one tribe dominating the interests of others. He began to speak revelations to this problem: all men and women in Medina had equal rights, whether or not they worshipped Allah.

Almost from the point of his arrival in Medina, Muhammad took on the role not just of prophet to the believers, but as civil authority over the unbelievers. Medina, like Mecca, was torn by conflict between clans and tribes; unlike Mecca, it was not controlled by a powerful cabal able to unite itself, when necessary, against a threat to its interests. Muhammad offered the city a path towards peace, and it was accepted. He began to achieve political power, not through conquest, but through his reputation for wisdom.

From its very beginnings, Islam was unlike Christianity in this way. The followers of Jesus, not to mention the disciples of Paul and the early bishops, had no cities of their own; they had no kingdom. Christianity became a religion of empires only when Constantine brought it into Rome with him, across the Milvian Bridge; and between Jesus and Constantine lay several centuries of belief and practice, theology and tradition, war and conquest.

But Muhammad had a city. From the day of the Hijra onward, his revelations governing the purity of worship and the morality of the believer were mixed with his need to make civil legislation for Medina. From the very beginning, his teachings were affected by his need to establish a political order. The man who had lost his father and mother, his family, his wife, and finally his home, had found a new family among the community of his followers. His greatest concern was to keep those followers together in one body, united with each other and with him in loyalty and oneness of purpose—and for that, he needed not just the judge’s balance scale, but also the sword of justice.

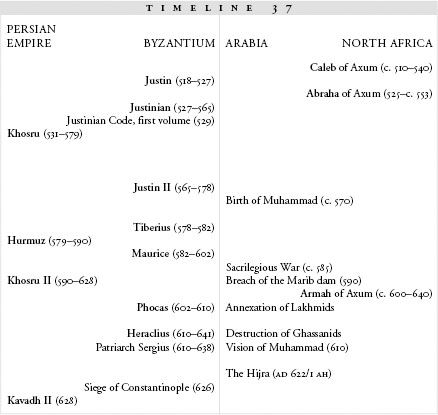

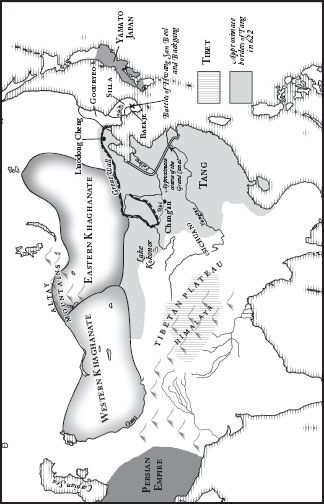

Between 622 and 676, the Tang empire of China battles with Tibet and the Turks and tries to take over the kingdom of Silla, while the Yamato dynasty of Japan joins in the resistance

B

Y

622,

THE NEW EMPEROR

of China, Tang Gaozu, had signed a peace with Goguryeo (bringing an end to the long bloody conflict started by the Sui) and had begun the task of refilling the imperial treasury (emptied by war and canal-building). Despite the frequent outbreaks of minor rebellion in the unsettled country, the Tang dynasty was finding its way carefully forward into stability.

The dynasty’s biggest problem came from the Turks to the north. After the death of the Turkish khan Bumin Khan, founder of the Turkish kingdom, Turkish unity had fractured from the inside and the kingdom had fallen apart into separate realms, the Eastern Khaghanate and the Western Khaghanate.

The Eastern Khaghanate was closest to the Tang border, and for a time Tang Gaozu managed to stay on reasonably good terms with the khagan. Gaozu’s own family was not so very different, in custom and language, from the Turks. He had grown up in the northern reaches of China, where the Turks and Chinese mingled along the border. Gaozu’s mother and grandmother had been of nomadic blood, and Gaozu himself had raised his sons as hunters and warriors, more interested in horses and hunting dogs than in Confucian classics.

1

But then the aggressive khan Hsieh-li took control of the Eastern Khaghanate. In the decades before Hsieh-li, the Eastern Turks had attacked the border, on average, about once every three years; under Hsieh-li’s rule, the Turks began to raid the northern Chinese lands once every two or three

months

. In 624, the army of the Eastern Khaghanate marched all the way down to the Yellow river and then crossed it. The Tang troops panicked; only the intervention of Li Shimin, the emperor’s second son, kept them from bolting. Li Shimin rode out and offered to challenge Hsieh-li to single combat—something no southern Chinese prince would ever have done—which struck the Turkish khan as the act of a man confident of victory. The khan began to suspect that his own men were in league with Li Shimin and that the duel was a trap. He refused to fight and instead accepted another huge payment and withdrew.

2

Tang Gaozu, the dynasty’s patriarch and founder, did not reign for much longer. He had served as the bringer of judgment on the previous dynasty’s excesses, but this role was not naturally compatible with a long and virtuous rule as holder of the Mandate of Heaven. Instead, his son Li Shimin would take on this job, ruling for over twenty years and bringing the Tang dynasty into full legitimacy.

Li Shimin had fought for his father in the wars that brought Tang Gaozu to the throne, and had earned a loyal following of his own through his bravery against the Turks. In 626, he murdered (possibly in self-defense) his older brother, the crown prince of the new dynasty, and asked his father to appoint him heir instead. Tang Gaozu agreed. A few months later he abdicated and gave his son the throne. Li Shimin became Tang Taizong, the second emperor of the dynasty: like his father, he had come to power through violence, but the force was partly veiled by his father’s decision to pass him the crown without struggle.

3

As soon as he was acclaimed emperor, the Eastern Turks invaded again. Again Li Shimin, now Tang Taizong, put his own body on the line. “The Turks think that because we have had internal troubles, we cannot muster an army,” he told his advisors. “If I were to close the city [the capital Chang’an], they would loot our territory. I will go out alone to show them that there is nothing to fear, and make a show of force to make them know I mean fighting.”

4

In fact, the Tang troops at Chang’an were too few to defeat the Turks, but Tang Taizong rode out with six men to the Wei river (just north of the city) anyway and reproached Hsieh-li for breaking their earlier peace. Meanwhile, his army assembled far enough away to make them difficult to count, but close enough for Hsieh-li to see them. Tang Taizong, exercising his knowledge of northern customs, then offered to go through a brotherhood ceremony with the Turkish khan, and Hsieh-li accepted.

5

The Turks went home, but Tang Taizong exercised his new brotherhood by doing his best to encourage Hsieh-li’s subjects to revolt against him; this was not so different from his relationship to his own brothers, two of whom he had killed on his way to the throne. He also encouraged Hsieh-li’s nephew to lead a coup d’etat. Civil war between uncle and nephew began in 629; the Tang armies marched up to “help,” and by 630, Tang Taizong had driven Hsieh-li into exile, accepted his nephew’s surrender, and named himself “Heavenly Khan of the Eastern Turks” as well as Tang emperor. The Tang empire had suddenly expanded—and Tang Taizong, once again showing his familiarity with northern affairs, managed to make himself popular with his new subjects by making tribal leaders into Tang court officials.

6

38.1: The East in the Seventh Century

For the next two decades, Tang Taizong led his kingdom into internal stability and outward conquest. Rather than making any great new innovations, he turned out to be expert at developing the network of government already traced out by the Sui; and he led his armies in expanding his control over the north, the northwest (where he conquered the eastern reaches of the Western Turkish Khaghanate with the help of his new Eastern Turkish subjects), and the southwest. His trust was placed not in scholars, but in men who, like himself, knew the northern methods of fighting: “Throughout his life,” wrote the poet Li Bai of the Tang soldiers, “the man of the marches never so much as opens a book, but he can hunt, he is skillful, strong, and bold.”

7

In the southwest, the Tang generals encountered another empire-builder; but unlike Tang Taizong, who was building an empire on someone else’s foundation, this king had laid his own groundwork. His name was Songtsen Gampo, and he lived on the high central Asian land known as the Tibetan plateau. The Tibetan tribes had come, thousands of years before, from the same area as the Chinese, but continued in a nomadic lifestyle long after the Chinese had started on the road to farming and town-building. Songtsen Gampo’s father, Namri Songtsen, was the leader of one of the Tibetan tribes. He had taken the first tentative steps towards dominating the neighboring tribes when he died, sometime between 618 and 620, and his son—perhaps fourteen at the time—inherited his title.

Like Clovis of the Franks far to the west or Bumin Khan of the Turks up in the Altay mountains, Songtsen Gampo began to work at the task of turning a collection of tribes into a kingdom. And like most tribal leaders turned king, he chose outward conquest as a way to make his new territory cohere. After 620, he brought the nearby tribes under his authority and then launched campaigns against the Tuyu-hun nomads, around Lake Kokonor to the northeast, possibly as a way to distract the other tribal chiefs from the unpleasant fact that they were now under his domination. He sent armies west toward India and east toward the Tang border, but his mind was not only on conquest: he also worked at making alliances with his neighbors, establishing for the first time a Tibetan foreign policy.

8

In 640, he sent an ambassador to the Tang court with a message: he wanted to make a marriage alliance with the ruling family.

Tang Taizong was unimpressed. In Tibet, Songtsen Gampo was a prodigy, a superstar statesman able to take his people from disorganized tribal structure to empire in less than a generation. In the universe of the Tang, he was merely a barbarian king with pretensions.

The Tang emperor refused to send a princess to the west, and Songtsen Gampo immediately invaded the southwestern territory of the Tang, the area now known as Sichuan. The Tang defensive garrisons managed to drive him back out, but Tang Taizong was surprised by the strength of the attack and decided that it would be prudent to rethink. He sent one of his nieces, Wen-ch’eng, westward to the court of Songtsen Gampo, and in 641 the two were married.

Wen-ch’eng seems to have brought with her Buddhist monks, Buddhist scriptures, and the Chinese habits of eating butter and cheese, drinking tea and wine, and consulting the stars. She was followed westward, in time, by experts she asked the Tang court to send: Chinese craftsmen who could teach the Tibetans how to make wine and paper, how to cultivate silkworms and build mills to grind grain, how to treat patients according to Chinese medical principles. Chinese culture—

northern

Chinese culture—infiltrated Songtsen Gampo’s empire. So did Indian ways; Wen-ch’eng also suggested that her husband send one of his officials into northern India to bring back principles of written Sanskrit. The Tibetans had had no written language, but by the end of Songtsen Gampo’s reign, a Tibetan script based on Sanskrit was in use.

9

Songtsen Gampo died in 650, after building an entire nation in a single lifetime. Like so many empires built on personal charisma, the Tibetan kingdom began to waver. His heir was his infant grandson Mangson Mangtsen, and the real power at the palace was the baby’s regent, the prime minister Gar Tongtsen. For a time, the empire halted its expansion and its foreign embassies, absorbed instead with an internal struggle for power and familiar conflicts between Buddhist worshippers and followers of the old nomadic religions.

Within months of Songtsen Gampo’s death, Tang Taizong also died. His throne went to a grown heir: his favorite son, Gaozong, who had been at his deathbed fasting and weeping and was rewarded with the crown.

In the year he was acclaimed emperor, Tang Gaozong also added a new wife to the consorts he already had. He rescued one of his own father’s concubines, Wu Zetian, from the Buddhist monastery where she had been sent after Taizong’s death. Apparently the two had been sleeping together for some time. In 656, over the protests of his courtiers, the emperor demoted his first wife and made Wu Zetian empress, naming her three-year-old son crown prince.

10

In the first years of his rule, Tang conquests continued. The Western Turkish Khaghanate had suffered a civil war between rival leaders, and in 657 the Tang armies marched through it, surprising the battling khans. The general in charge of the western front, Su Dingfang, rounded up his troops in a blizzard and sent them in for attack through two feet of snow: “The fog sheds darkness everywhere,” he told them. “The wind is icy. The barbarians do not believe that we can campaign at this season. Let us hasten to surprise them!” The unprepared soldiers of the Western Turks were defeated, the land of the Khaghanate reduced to a Tang protectorate.

11

Now the Tang empire stretched all the way to the borders of Persia. But on the cusp of a domination unlike any before, the emperor Tang Gaozong fell ill. Contemporary accounts tell us that he suffered from devastating headaches and dizziness, and lost his eyesight for a time. He had probably suffered a stroke, and in his weakness he relied on the intelligent and well-educated Wu Zetian, asking her to read him his state papers and authorizing her to make decisions in his name.

12

She was in this position of power when ambassadors came to the Tang court from the Korean kingdom of Silla, asking for aid. The king of Silla, Muyeol the Great, still ruled the strongest kingdom on the peninsula, but he had watched his neighbors, Goguryeo and Baekje, forge friendships with the Wa of Japan, and the triple alliance alarmed him.

Wu Zetian agreed to send a Tang army of 130,000 to help Silla fight against Baekje, and in a great battle at Hwang San Beol, on the border between the two kingdoms, the Baekje army was devastated. The Baekje king, Uija, surrendered and was taken off as a prisoner—not to Silla, but to China. Wu Zetian had her eye on the Korean peninsula, and the Tang reinforcements had been a gentle probe into Korean territory.

Muyeol the Great declared himself king of Silla and Baekje, but Baekje rebels were already organizing a resistance. Survivors of the Battle of Hwang San Beol fled to Japan, where one of the captive king’s sons already lived; he had gone to Japan some years before as a hostage and guarantor of the alliance between Japan and Baekje.

There, they appealed to Prince Naka no Oe, the crown prince of the Yamato dynasty, to help them get their country back.

T

HE HEAVENLY SOVEREIGN

of Japan, the empress Saimei, had taken the throne in 642 after her husband’s death. Her son Naka no Oe, sixteen years old, was perhaps a more natural choice—but the powerful Soga clan had thrown its weight behind Saimei, who was less independent-minded than her energetic son. In 593, the Soga had managed to put a dead emperor’s wife on the throne and then control it from behind the dais. Now they repeated the feat, making Saimei the second woman to occupy the throne of Japan and the second to depend on the Soga for her power.

Naka no Oe was both old enough to rule and ambitious enough to resent this. He did not blame his mother; he blamed the Soga, and he began to lay plans to break their power. He found a willing ally in a senior member of the rival Nakatomi clan, Nakatomi no Kamatari. Together with a resentful younger member of the Soga clan itself, they plotted to get rid of the Soga influence by assassinating the most powerful members of its most senior family. Their primary target was Soga no Iruka, who together with his father Soga no Emishi had stood behind the empress’s accession, and who together with his father stood to gain the most power by controlling the heavenly sovereign.