The Grand Alliance (48 page)

Read The Grand Alliance Online

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II

The Grand Alliance

291

we might even feel strong enough to reinforce from

Egypt. I am most reluctant to see us quit, and if the

troops were British only and the matter could be

decided on military grounds alone, I would urge Wilson

to fight if he thought it possible. Anyhow, before we

commit ourselves to evacuation the case must be put

squarely to the Dominions after tomorrow’s Cabinet. Of

course, I do not know the conditions in which our

retreating forces will reach the new key position.

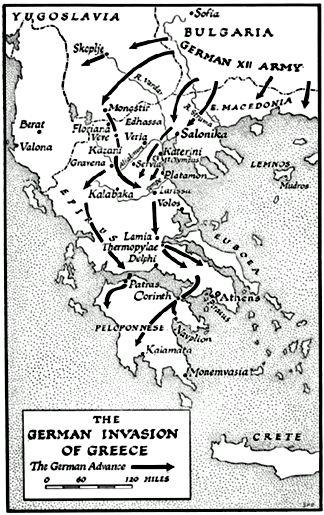

On the twenty-first General Wavell asked the King about the state of the Greek Army and whether it could give immediate and effective aid to the left flank of the Thermopylae position. His Majesty said that time rendered it impossible for any organised Greek force to support the British left flank before the enemy could attack. General Wavell replied that in that case he felt that it was his duty to take immediate steps for re-embarkation of such portion of his army as he could extricate. The King entirely agreed, and seemed to have expected this. He spoke with deep regret of having been the means of placing the British forces in such a position. General Wavell then impressed on His Majesty the need for absolute secrecy and for all measures to be taken that would make the re-embarkation possible – for instance, that order should be preserved in Athens and that the departure of the King and Government for Crete should be delayed as long as possible; also that the Greek army in Epirus should stand firm and prevent any chance of an enemy advance from the west along the north shores of the Gulf of Corinth. The King promised what help he could. But all was vain. The final surrender of Greece to overwhelming German might was made on April 24.

The Grand Alliance

292

We were now confronted with another of those evacuations by sea which we had endured in 1940. The organised withdrawals of over fifty thousand men from Greece under the conditions prevailing might well have seemed an almost hopeless task. It was, however, accomplished by the Royal Navy under the direction of Vice-Admiral Pridham-Wippell afloat and Rear-Admiral Baillie-Grohman with Army Headquarters ashore. At Dunkirk on the whole we had air mastery. In Greece the Germans were in complete and undisputed control of the air and could maintain an almost continuous attack on the ports and on the retreating army. It was obvious that embarkation could only take place by night, and, moreover, that troops must avoid being seen near the beaches in daylight. This was Namsos over again, and on ten times the scale.

Admiral Cunningham threw nearly the whole of his light forces, including six cruisers and nineteen destroyers, into the task. Working from the small ports and beaches in Southern Greece, these ships, together with eleven transports and assault ships and many smaller craft, began the work of rescue on the night of April 24.

For five successive nights the work continued. On the twenty-sixth the enemy captured the vital bridge over the Corinth Canal by parachute attack, and thereafter German troops poured into the Peloponnese, harrying our hard-pressed soldiers as they strove to reach the southern beaches. During the nights of the twenty-fourth and twenty-fifth 17,000 men were brought out, with the loss of two transports. On the following night about 19,500 were got away from five embarkation points. At Nauplion there was disaster. The transport

Slamatf

in a gallant but misguided effort to embark the maximum stayed too long in the anchorage. Soon after dawn, when clearing the land, she The Grand Alliance

293

was attacked and sunk by dive-bombers. The destroyers

Diamond

and

Wryneck,

who rescued most of the seven hundred men on board, were both in turn sunk by air attack a few hours later. There were only fifty survivors from all three ships.

The Grand Alliance

294

The Grand Alliance

295

On the twenty-eighth and twenty-ninth efforts were made by two cruisers and six destroyers to rescue 8000 troops and 1400 Yugoslav refugees from the beaches near Kalamata.

A destroyer sent on ahead to arrange the embarkation found the enemy in possession of the town and large fires burning, and the main operation had to be abandoned.

Although a counter-attack drove the Germans out of the town, only about 450 men were rescued from beaches to the eastward by four destroyers, using their own boats. On the same night the

Ajax

and three destroyers rescued 4300

from Monemvasia.

These events marked the end of the main evacuation.

Small isolated parties were picked up in various islands or in small craft at sea during the next two days, and 1400

officers and men, aided by the Greeks at mortal peril, made their way back to Egypt independently in later months.

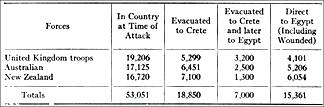

The following table gives the final evacuation figures for the Army:

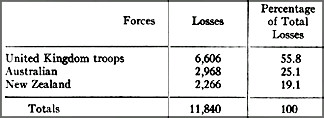

The losses were:

The Grand Alliance

296

In all 50,662 were safely brought out, including men of the Royal Air Force and several thousand Cypriots, Palestinians, Greeks, and Yugoslavs. This figure represented about eighty per cent of the forces originally sent into Greece. These results were only made possible by the determination and skill of the seamen of the Royal and Allied Merchant Navies, who never faltered under the enemy’s most ruthless efforts to halt their work. From April 21 until the end of the evacuation twenty-six ships were lost by air attack. Twenty-one of these were Greek and included five hospital ships. The remainder were British and Dutch.

The Royal Air Force, with a fleet air arm contingent from Crete, did what they could to relieve the situation, but they were overwhelmed by numbers. Nevertheless, from November onward the few squadrons sent to Greece had done fine service. They inflicted on the enemy confirmed losses of 231 planes and had dropped 500 tons of bombs.

Their own losses of 209 machines, of which 72 were in combat, were severe, their record exemplary.

The small but efficient Greek Navy now passed under British control. A cruiser, six modern destroyers, and four submarines escaped to Alexandria, where they arrived on April 25. Thereafter the Greek Navy was represented with distinction in many of our operations in the Mediterranean.

The Grand Alliance

297

If in telling this tale of tragedy the impression is given that the Imperial and British forces received no effective military assistance from their Greek allies, it must be remembered that these three weeks of April fighting at desperate odds were for the Greeks the culmination of the hard five months’

struggle against Italy in which they had expended almost the whole life-strength of their country. Attacked in October without warning by at least twice their numbers, they had first repulsed the invaders and then in counter-attack had beaten them back forty miles into Albania. Throughout the bitter winter in the mountains they had been at close grips with a more numerous and better-equipped foe. The Greek Army of the Northwest had neither the transport nor the roads for a rapid manoeuvre to meet at the last moment the new overpowering German attack cutting in behind its flank and rear. Its strength had already been strained almost to the limit in a long and gallant defence of the homeland.

There were no recriminations. The friendliness and aid which the Greeks had so faithfully shown to our troops endured nobly to the end. The people of Athens and at other points of evacuation seemed more concerned for the safety of their would-be rescuers than with their own fate.

Greek martial honour stands undimmed.

I have now set forth in narrative the outstanding facts of our adventure in Greece. After things are over, it is easy to choose the fine mental and moral positions which one should adopt. In this account I have recorded events as they occurred and action as it was taken. Later on these can be judged in the glare of consequences; and finally, The Grand Alliance

298

when our lives have faded, History will pronounce its cool, detached, and shadowy verdict.

There is no doubt that the Mussolini-Hitler crime of overrunning Greece, and our effort to stand against tyranny and save what we could from its claws, appealed profoundly to the people of the United States, and above all to the great man who led them. I had at this moment a moving interchange of telegrams with the President.