The End of Growth: Adapting to Our New Economic Reality (25 page)

Read The End of Growth: Adapting to Our New Economic Reality Online

Authors: Richard Heinberg

Tags: #BUS072000

That price trend seems to have reversed. During the past decade, production rates for many industrially important non-renewable resources have leveled off or, in some cases, begun to decline, while prices have risen.

78

Several recent articles, reports, and studies highlight the predicament of depleting mines, declining ore quality, and rising prices.

79

Data from the US Geological Survey shows that within the US many mineral resources are well past their peak rates of production.

80

These include bauxite (whose production peaked in 1943), copper (1998), iron ore (1951), magnesium (1966), phosphate rock (1980), potash (1967), rare earth metals (1984), tin (1945), titanium (1964), and zinc (1969).

81

As Tom Graedel at Yale University pointed out in a 2006 paper, “Virgin stocks of several metals appear inadequate to sustain the modern ‘developed world’ quality of life for all of Earth’s people under contemporary technology.”

82

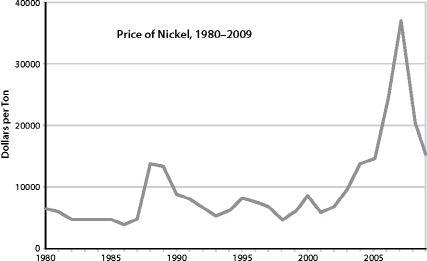

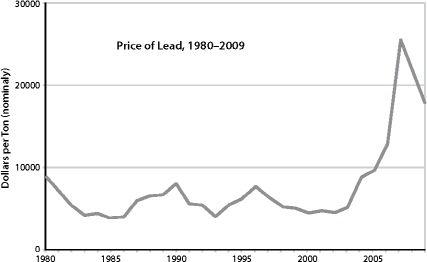

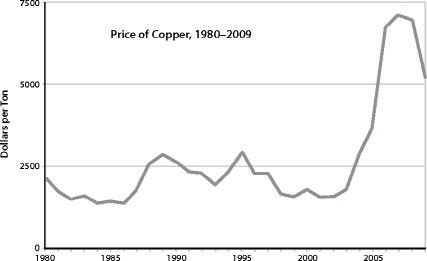

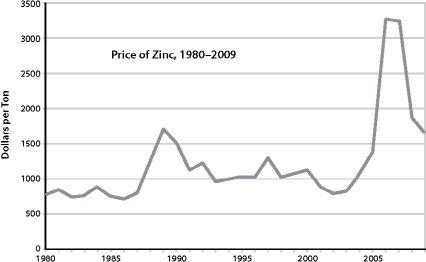

FIGURE 35.

Commodity Prices, 1980–2009.

Source: UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTD).

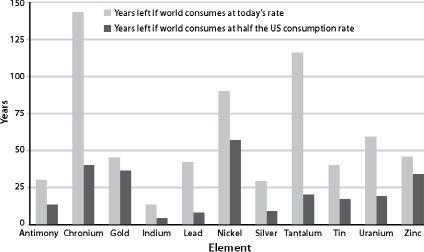

FIGURE 36.

Depleting Elements.

If nothing changed in our consumption patterns for the above elements, their supply would dwindle relatively slowly (represented in light grey). However, as more countries industrialize, consumption is likely to increase. If the world consumes these resources at only half the current US rate, they will all run out within 60 years (represented in dark grey). Source: Armin Reller of University of Augsburg, Tom Graedel of Yale University, Australian Academy of Science.

The following are just a few examples.

For thousands of years, metal smiths made tools from melted-down “bog iron” (which was mainly composed of an iron-rich ore called goethite), using charcoal as a fuel. In the more recent past iron miners began to extract lower-grade ores such as natural hematite, which were then smelted in coke-fed blast furnaces. Today miners must rely more heavily on taconite, a flint-like ore containing less than 30 percent magnetite and hematite.

83

According to Julian Phillips, editor of

Gold Forecaster

newsletter, deposits of gold that can be easily mined will probably be exhausted in about 20 years.

84

There are 17 rare earth elements (REEs) with names like lanthanum, neodymium, europium, and yttrium. They are critical to a variety of high-tech products including catalytic converters, color TV and flat panel displays, permanent magnets, batteries for hybrid and electric vehicles, and medical devices; to manufacturing processes like petroleum refining; and to various defense systems like missiles, jet engines, and satellite components. REEs are even used in making the giant electromagnets in modern wind turbines. But rare earth mines are failing to keep up with demand. China produces 97 percent of the world’s REEs, and has issued a series of contradictory public statements about whether, and in what amounts, it intends to continue exporting these elements. The options for other nations, such as the US, are to find substitutes for REEs or to identify new economically viable REE reserves elsewhere in the world.

85

Indium is used in indium tin oxide, which is a thin-film conductor in flat-panel television screens. Armin Reller, a materials chemist, and his colleagues at the University of Augsburg in Germany, have been investigating the problem of indium depletion. Reller estimates that the world has, at best, 10 years before production begins to decline; known deposits will be exhausted by 2028, so new deposits will have to be found and developed.

86

Some analysts are now suggesting that shortages of energy minerals including indium, REEs, and lithium for electric car batteries could trigger trade wars.

87

Armin Reller and his colleagues have also looked into gallium supplies. Discovered in 1831, gallium is a blue-white metal with certain unusual properties, including a very low melting point and an unwillingness to oxidize. These make it useful as a coating for optical mirrors, a liquid seal in strongly heated apparatus, and a substitute for mercury in ultraviolet lamps. Gallium is also essential to making liquid-crystal displays in cell phones, flat-screen televisions, and computer monitors. With the explosive profusion of LCD displays in the past decade, supplies of gallium have become critical; Reller projects that by about 2017 existing sources will be exhausted.

88

Palladium (along with platinum and rhodium) is a primary component in the autocatalysts used in automobiles to reduce exhaust emissions. Palladium is also employed in the production of multi-layer ceramic capacitors in cellular telephones, personal and notebook computers, fax machines, and auto and home electronics. Russian stockpiles have been a key component in world palladium supply for years, but those stockpiles are nearing exhaustion, and prices for the metal have soared as a result.

89

Uranium is the fuel for nuclear power plants and is also used in nuclear weapons manufacturing; small amounts are employed in the leather and wood industries for stains and dyes, and as mordants of silk or wool. Depleted uranium is used in kinetic energy penetrator weapons and armor plating. In 2006, the Energy Watch Group of Germany studied world uranium supplies and issued a report concluding that, in its most optimistic scenario, the peak of world uranium production will be achieved before 2040. If large numbers of new nuclear power plants are constructed to offset the use of coal as an electricity source, then supplies will peak much sooner.

90

Tantalum for cell phones. Helium for blimps. The list could go on. Perhaps it is not too much of an exaggeration to say that humanity is in the process of achieving Peak Everything.

91

BOX 3.9

Depletion

As a rule of thumb, when the quality of the ore drops, the amount of energy required to extract the resource rises (often the amount of water, too).

Mining companies around the world are reporting declining ore quality, and are using increasing amounts of energy in mining and refining. However, our main sources of energy (fossil fuels) are also depleting non-renewable resources with declining quality. Once energy starts to become scarce and expensive, this sets off a self-reinforcing feedback loop: declining energy supplies make resource extraction more problematic; but since metals and other minerals are essential to energy production, this only makes the energy problem worse, which makes the materials problem worse, which makes the energy problem worse....

92

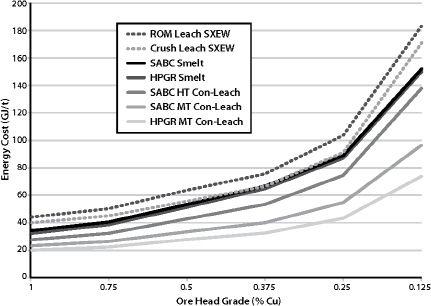

FIGURE 37.

Energy Cost of copper production as a function of ore grade.

As ore grade declines, energy costs of resource recovery increase. This graph tracks costs of copper production, but the principle could easily be illustrated for other minerals. Source: J. O. Marsden. Hydrometallurgy 2008: Proceedings of the Sixth International Symposium: Energy Efficiency and Copper Hydrometallurgy, Edited by C. A. Young, SME (2008).

Climate Change, Pollution, Accidents,

Environmental Decline, and Natural Disasters

Accidents and natural disasters have long histories; therefore it may seem peculiar to think that these could now suddenly become significant factors in choking off economic growth. However, two things have changed.

First, growth in human population and proliferation of urban infrastructure are leading to ever more serious impacts from natural and human-caused disasters. Consider, for example, the magnitude 8.7 to 9.2 earthquake that took place on January 26 of the year 1700 in the Cascadia region of the American northwest. This was one of the most powerful seismic events in recent centuries, but the number of human fatalities, though unrecorded, was probably quite low. If a similar quake were to strike today in the same region — encompassing the cities of Vancouver, Canada; Seattle, Washington; and Portland, Oregon — the cost of damage to homes and commercial buildings, highways, and other infrastructure could reach into the hundreds of billions of dollars, and the human toll might be horrific. Another, less hypothetical, example: the lethality of the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, which killed between 200,000 and 300,000 people, was exacerbated by the extreme population density of the low-lying coastal areas of Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and India.