The Complete Yes Minister (8 page)

‘One: if we do nothing we implicitly agree with the speech. Two: if we issue a statement we just look foolish. Three: if we lodge a protest it will be ignored. Four: we can’t cut off aid because we don’t give them any. Five: if we break off diplomatic relations we cannot negotiate the oil rig contracts. Six: if we declare war it just

might

look as if we were over-reacting.’ He paused. ‘Of course, in the old days we’d have sent in a gunboat.’

might

look as if we were over-reacting.’ He paused. ‘Of course, in the old days we’d have sent in a gunboat.’

I was desperate by this time. I said, ‘I suppose that is absolutely out of the question?’

They all gazed at me in horror. Clearly it is out of the question.

Bernard had absented himself during Humphrey’s résumé of the possibilities. Now he squeezed back into the compartment.

‘The Permanent Under-Secretary to the Foreign and Commonwealth Office is coming down the corridor,’ he announced.

‘Oh terrific,’ muttered Bill Pritchard. ‘It’ll be like the Black Hole of Calcutta in here.’

Then I saw what he meant. Sir Frederick Stewart, Perm. Sec. of the FCO, known as ‘Jumbo’ to his friends, burst open the door. It smashed Bernard up against the wall. Martin went flying up against the washbasin, and Humphrey fell flat on his face on the bunk. The mighty mountain of lard spoke:

‘May I come in, Minister?’ He had a surprisingly small high voice.

‘You can try,’ I said.

‘This is all we needed,’ groaned Bill Pritchard as the quivering mass of flesh forced its way into the tiny room, pressing Bill up against the mirror and me against the window. We were all standing extremely close together.

‘Welcome to the Standing Committee,’ said Humphrey as he propped himself precariously upright.

‘What do we do about this hideous thing? This hideous

speech

, I mean,’ I added nervously, in case Jumbo took offence. His bald head shone, reflecting the overhead lamp.

speech

, I mean,’ I added nervously, in case Jumbo took offence. His bald head shone, reflecting the overhead lamp.

‘Well now,’ began Jumbo, ‘I think we know what’s behind this, don’t we Humpy?’

Humpy? Is this his nickname? I looked at him with new eyes. He clearly thought I was awaiting a response.

‘I think that Sir Frederick is suggesting that the offending paragraph of the speech may be, shall we say, a bargaining counter.’

‘A move in the game,’ said Jumbo.

‘The first shot in a battle,’ said Humphrey.

‘An opening gambit,’ said Bernard.

These civil servants are truly masters of the cliché. They can go on all night. They do, unless stopped. I stopped them.

‘You mean, he wants something,’ I said incisively. It’s lucky someone was on the ball.

‘If he doesn’t,’ enquired Jumbo Stewart, ‘why give us a copy in advance?’ This seems unarguable. ‘But unfortunately the usual channels are blocked because the Embassy staff are all new and we’ve only just seen the speech. And no one knows anything about this new President.’

I could see Humphrey giving me meaningful looks.

‘I do,’ I volunteered, slightly reluctantly.

Martin looked amazed. So did Jumbo.

‘They were at University together.’ Humphrey turned to me. ‘The old-boy network?’ It seemed to be a question.

I wasn’t awfully keen on this turn of events. After all, it’s twenty-five years since I saw Charlie, he might not remember me, I don’t know what I can achieve. ‘I think you ought to see him, Sir Frederick,’ I replied.

‘Minister, I think you carry more weight,’ said Jumbo. He seemed unaware of the irony.

There was a pause, during which Bill Pritchard tried unsuccessfully to disguise a snigger by turning it into a cough.

‘So we’re all agreed,’ enquired Sir Humphrey, ‘that the mountain should go to Mohammed?’

‘No,

Jim’s

going,’ said Martin, and got a very nasty look from his overweight Perm. Sec. and more sounds of a press officer asphyxiating himself.

Jim’s

going,’ said Martin, and got a very nasty look from his overweight Perm. Sec. and more sounds of a press officer asphyxiating himself.

I realised that I had no choice. ‘All right,’ I agreed, and turned to Sir Humphrey, ‘but you’re coming with me.’

‘Of course, said Sir Humphrey, ‘I’d hardly let you do it on your own.’

Is this

another

insult, or is it just my paranoia?

another

insult, or is it just my paranoia?

Later today:

Charlie Umtali – perhaps I’d better call him President Selim from now on – welcomed us to his suite at the Caledonian Hotel at 10 a.m.

‘Ah Jim.’ He rose to greet us courteously. I had forgotten what beautiful English he spoke. ‘Come in, how nice to see you.’

I was actually rather, well, gratified by this warm reception.

‘Charlie,’ I said. We shook hands. ‘Long time no see.’

‘You don’t have to speak pidgin English to me,’ he said, turned to his aide, and asked for coffee for us all.

I introduced Humphrey, and we all sat down.

‘I’ve always thought that Permanent Under-Secretary is such a demeaning title,’ he said. Humphrey’s eyebrows shot up.

‘I beg your pardon?’

‘It sounds like an assistant typist or something,’ said Charlie pleasantly, and Humphrey’s eyebrows disappeared into his hairline. ‘Whereas,’ he continued in the same tone, ‘you’re really in charge of everything, aren’t you?’ Charlie hasn’t changed a bit.

Humphrey regained his composure and preened. ‘Not quite everything.’

I then congratulated Charlie on becoming Head of State. ‘Thank you,’ he said, ‘though it wasn’t difficult. I didn’t have to do any of the boring things like fighting elections.’ He paused, and then added casually, ‘Or by-elections,’ and smiled amiably at us.

Was this a hint? I decided to say nothing. So after a moment he went on. ‘Jim, of course I’m delighted to see you, but is this purely a social visit or is there anything you particularly wanted to talk about? Because I do have to put the finishing touches to my speech.’

Another hint?

I told him we’d seen the advance copy. He asked if we liked it. I asked him if, as we were old friends, I could speak frankly. He nodded.

I tried to make him realise that the bit about colonialist oppression was slightly – well, really,

profoundly

embarrassing. I asked him if he couldn’t just snip out the whole chunk about the Scots and the Irish.

profoundly

embarrassing. I asked him if he couldn’t just snip out the whole chunk about the Scots and the Irish.

Charlie responded by saying, ‘This is something that I feel very deeply to be true. Surely the British don’t believe in suppressing the truth?’

A neat move.

Sir Humphrey then tried to help. ‘I wonder if there is anything that might persuade the President to consider recasting the sentence in question so as to transfer the emphasis from the specific instance to the abstract concept, without impairing the conceptual integrity of the theme?’

Some help.

I sipped my coffee with a thoughtful expression on my face.

Even Charlie hadn’t got it, I don’t think, because he said, after quite a pause: ‘While you’re here, Jim, may I sound you out on a proposal I was going to make to the Prime Minister at our talks?’

I nodded.

He then told us that his little change of government in Buranda had alarmed some of the investors in their oil industry. Quite unnecessarily, in his view. So he wants some investment from Britain to tide him over.

At last we were talking turkey.

I asked how much. He said fifty million pounds.

Sir Humphrey looked concerned. He wrote me a little note. ‘Ask him on what terms.’ So I asked.

‘Repayment of the capital not to start before ten years. And interest free.’

It sounded okay to me, but Humphrey choked into his coffee. So I pointed out that fifty million was a lot of money.

‘Oh well, in that case . . .’ began Charlie, and I could see that he was about to end the meeting.

‘But let’s talk about it,’ I calmed him down. I got another note from Humphrey, which pointed out that, if interest ran at ten per cent on average, and if the loan was interest free for ten years, he was in effect asking for a free gift of fifty million pounds.

Cautiously, I put this point to Charlie. He very reasonably (I thought) explained that it was all to our advantage, because they would use the loan to buy oil rigs built on the Clyde.

I could see the truth of this, but I got another frantic and, by now, almost illegible note from Humphrey, saying that Charlie wants us to give him fifty million pounds so that he can buy our oil rigs with our money. (His underlinings, I may say.)

We couldn’t go on passing notes to each other like naughty schoolboys, so we progressed to muttering. ‘It sounds pretty reasonable to me,’ I whispered.

‘You can’t be serious,’ Humphrey hissed.

‘Lots of jobs,’ I countered, and I asked Charlie, if we did such a deal, would he make appropriate cuts in his speech? This was now cards on the table.

Charlie feigned surprise at my making this connection, but agreed that he would make cuts. However, he’d have to know right away.

‘Blackmail,’ Sir Humphrey had progressed to a stage whisper that could be heard right across Princes Street.

‘Are you referring to me or to my proposal?’ asked Charlie.

‘Your proposal, naturally,’ I said hastily and then realised this was a trick question. ‘No, not even your proposal.’

I turned to Humphrey, and said that I thought we could agree to this. After all, there are precedents for this type of deal.

3

3

Sir Humphrey demanded a private word with me, so we went and stood in the corridor.

I couldn’t see why Humphrey was so steamed up. Charlie had offered us a way out.

Humphrey said we’d never get the money back, and therefore he could not recommend it to the Treasury and the Treasury would never recommend it to Cabinet. ‘You are proposing,’ he declared pompously, ‘to buy your way out of a political entanglement with fifty million pounds of public money.’

I explained that this is diplomacy. He said it was corruption. I said ‘GCB,’ only just audibly.

There was a long pause.

‘What did you say, Minister?’

‘Nothing,’ I said.

Humphrey suddenly looked extremely thoughtful. ‘On the other hand . . .’ he said, ‘. . . we don’t want the Soviets to invest in Buranda, do we?’ I shook my head. ‘Yes, I see what you mean,’ he murmured.

‘And they will if we don’t,’ I said, helping him along a bit.

Humphrey started to marshal all the arguments on my side. ‘I suppose we could argue that we, as a part of the North/South dialogue, have a responsibility to the . . .’

‘TPLACs?’ I said.

Humphrey ignored the crack. ‘Quite,’ he said. ‘And if we were to insist on one per cent of the equity in the oil revenues ten years from now . . . yes, on balance, I think we can draft a persuasive case in terms of our third-world obligations, to bring in the FCO . . . and depressed area employment, that should carry with us both the Department of Employment and the Scottish Office . . . then the oil rig construction should mobilise the Department of Trade and Industry, and if we can reassure the Treasury that the balance of payments wouldn’t suffer . . . Yes, I think we might be able to mobilise a consensus on this.’

I thought he’d come to that conclusion. We trooped back into Charlie’s room.

‘Mr President,’ said Sir Humphrey, ‘I think we can come to terms with each other after all.’

‘You know my price,’ said Charlie.

‘And you know mine,’ I said. I smiled at Sir Humphrey. ‘Everyone has his price, haven’t they?’

Sir Humphrey looked inscrutable again. Perhaps this is why they are called mandarins.

‘Yes Minister,’ he replied.

1

K means Knighthood. KCB is Knight Commander of the Bath. G means Grand Cross. GCB is Knight Grand Cross of the Bath.

K means Knighthood. KCB is Knight Commander of the Bath. G means Grand Cross. GCB is Knight Grand Cross of the Bath.

2

FROLINAT was the National Liberation Front of Chad, a French acronym. FRETELIN was the Trust For the Liberation of Timor, a small Portuguese colony seized by Indonesia: a Portuguese acronym. ZIPRA was the Zimbabwe People’s Revolutionary Army, ZANLA the Zimbabwe African Liberation Army, ZAPU the Zimbabwe African People’s Union, ZANU the Zimbabwe African National Union, CARECOM is the acronym for the Caribbean Common Market and COREPER the Committee of Permanent Representatives to the European Community – a French acronym, pronounced co-ray-pair. ECOSOC was the Economic and Social Council of the UN, UNIDO the United Nations Industrial Development Organisation, IBRD the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and OECD was the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. GRAPO could not conceivably have been relevant to the conversation, as it is the Spanish acronym for the First of October Anti-Fascist Revolutionary Group.

FROLINAT was the National Liberation Front of Chad, a French acronym. FRETELIN was the Trust For the Liberation of Timor, a small Portuguese colony seized by Indonesia: a Portuguese acronym. ZIPRA was the Zimbabwe People’s Revolutionary Army, ZANLA the Zimbabwe African Liberation Army, ZAPU the Zimbabwe African People’s Union, ZANU the Zimbabwe African National Union, CARECOM is the acronym for the Caribbean Common Market and COREPER the Committee of Permanent Representatives to the European Community – a French acronym, pronounced co-ray-pair. ECOSOC was the Economic and Social Council of the UN, UNIDO the United Nations Industrial Development Organisation, IBRD the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and OECD was the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. GRAPO could not conceivably have been relevant to the conversation, as it is the Spanish acronym for the First of October Anti-Fascist Revolutionary Group.

It is not impossible that Sir Humphrey may have been trying to confuse his Minister.

3

Hacker might perhaps have been thinking of the Polish shipbuilding deal during the Callaghan government, by which the UK lent money interest free to the Poles, so that they could buy oil tankers from us with our money, tankers which were then going to compete against our own shipping industry. These tankers were to be built on Tyneside, a Labour-held marginal with high unemployment. It could have been said that the Labour government was using public money to buy Labour votes, but no one did – perhaps because, like germ warfare, no one wants to risk using an uncontrollable weapon that may in due course be used against oneself.

Hacker might perhaps have been thinking of the Polish shipbuilding deal during the Callaghan government, by which the UK lent money interest free to the Poles, so that they could buy oil tankers from us with our money, tankers which were then going to compete against our own shipping industry. These tankers were to be built on Tyneside, a Labour-held marginal with high unemployment. It could have been said that the Labour government was using public money to buy Labour votes, but no one did – perhaps because, like germ warfare, no one wants to risk using an uncontrollable weapon that may in due course be used against oneself.

3

The Economy Drive

December 7th

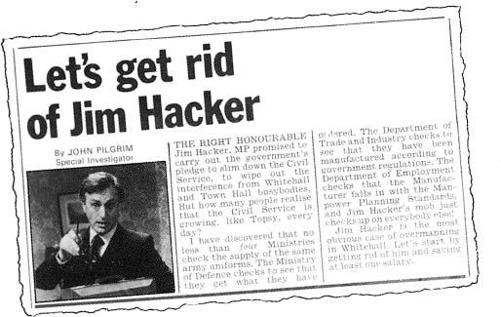

On the train going up to town after a most unrestful weekend in the constituency, I opened up the

Daily Mail

. There was a huge article making a personal attack on me.

Daily Mail

. There was a huge article making a personal attack on me.

I looked around the train. Normally the first-class compartment is full of people reading

The Times

, the

Telegraph

, or the

Financial Times

. Today they all seemed to be reading the

Daily Mail

.

The Times

, the

Telegraph

, or the

Financial Times

. Today they all seemed to be reading the

Daily Mail

.

Other books

The Reluctant Queen by Freda Lightfoot

Lawfully Yours by Hoff, Stacy

This is the Way the World Ends by James Morrow

Wink by Eric Trant

Luxury Model Wife by Downs,Adele

Erotic Research by Mari Carr

Bluebells on the Hill by Barbara McMahon

Duplicity Dogged the Dachshund by Blaize Clement

Tinkerbell on Walkabout by Maya Kaathryn Bohnhoff

The Secret Lives of Hoarders: True Stories of Tackling Extreme Clutter by Matt Paxton, Phaedra Hise