The Complete Yes Minister (5 page)

This wonderfully fortunate oversight seems to have saved my bacon. Of course, I didn’t let Humphrey see my great sense of relief. In fact, he apologised.

‘The fault is entirely mine, Minister,’ he said. ‘This procedure for holding up press releases dates back to before the era of Open Government. I unaccountably omitted to rescind it. I do hope you will forgive this lapse.’

In the circumstances, I felt that the less said the better. I decided to be magnanimous. ‘That’s quite all right Humphrey,’ I said, ‘after all, we all make mistakes.’

‘Yes Minister,’ said Sir Humphrey.

1

‘Hacker’s constituency party Chairman.

‘Hacker’s constituency party Chairman.

2

Frank Weisel.

Frank Weisel.

2

The Official Visit

November 10th

I am finding that it is impossible to get through all the work. The diary is always full, speeches constantly have to be written and delivered, and red boxes full of papers, documents, memos, minutes, submissions and letters have to be read carefully every night. And this is only

part

of my work.

part

of my work.

Here I am, attempting to function as a sort of managing director of a very large and important business and I have no previous experience either of the Department’s work or, in fact, of management of any kind. A career in politics is no preparation for government.

And, as if becoming managing director of a huge corporation were not enough, I am also attempting to do it part-time. I constantly have to leave the DAA to attend debates in the House, to vote, to go to Cabinet and Cabinet committees and party executive meetings and I now see that it is not possible to do this job properly or even adequately. I am rather depressed.

Can anyone seriously imagine the chairman of a company leaping like a dervish out of a meeting in his office every time a bell rings, no matter when, at any time of the afternoon or evening, racing like Steve Ovett to a building eight minutes down the street, rushing through a lobby, and running back to his office to continue the meeting. This is what I have to do every time the Division Bell rings. Sometimes six or seven times in one night. And do I have any idea at all what I’m voting for? Of course I don’t. How could I?

Today I arrived in the office and was immediately cast down by the sight of my in-tray. Full to overflowing. The out-tray was completely empty.

Bernard was patiently waiting for me to read some piece of impenetrable prose that he had dug up, in answer to the question I had asked him yesterday: what are my actual powers in various far-flung parts of the UK, such as Scotland and Northern Ireland?

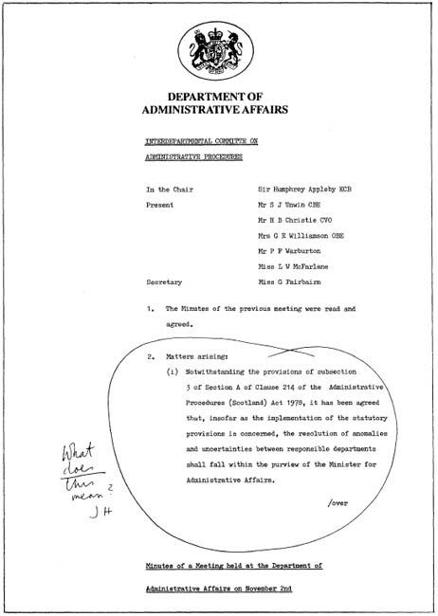

He proudly offered me a document. It said: ‘Notwithstanding the provisions of subsection 3 of Section A of Clause 214 of the Administrative Procedures (Scotland) Act 1978, it has been agreed that, insofar as the implementation of the statutory provisions is concerned, the resolution of anomalies and uncertainties between responsible departments shall fall within the purview of the Minister for Administrative Affairs.’

I gazed blankly at it for what seemed an eternity. My mind just seemed to cloud over, as it used to at school when faced with Caesar’s Gallic Wars or calculus. I longed to sleep. And it was only 9.15 a.m. I asked Bernard what it meant. He seemed puzzled by the question. He glanced at his own copy of the document.

‘Well, Minister,’ he began, ‘it means that notwithstanding the provisions of subsection 3 of Section A of Clause 214 of . . .’

I interrupted him. ‘Don’t read it to me,’ I said. ‘I’ve just read it to you. What does it

mean

?’

mean

?’

Bernard gazed blankly at me. ‘What it says, Minister.’

He wasn’t trying to be unhelpful. I realised that Whitehall papers, though totally incomprehensible to people who speak ordinary English, are written in the everyday language of Whitehall Man.

Bernard hurried out into the Private Office and brought me the diary.

[

The Private Office is the office immediately adjoining the Minister’s office. In it are the desks of the Private Secretary and the three or four assistant private secretaries, including the Diary Secretary – a full-time job. Adjoining the inner Private Office is the outer private office, containing about twelve people, all secretarial and clerking staff, processing replies to parliamentary questions, letters, etc

.

The Private Office is the office immediately adjoining the Minister’s office. In it are the desks of the Private Secretary and the three or four assistant private secretaries, including the Diary Secretary – a full-time job. Adjoining the inner Private Office is the outer private office, containing about twelve people, all secretarial and clerking staff, processing replies to parliamentary questions, letters, etc

.

Access to the Minister’s office is through the Private Office. Throughout the day everyone, whether outsiders or members of the Department, continually come and go through the Private Office

.

.

The Private Office is, therefore, somewhat public – Ed

.]

.]

‘May I remind you, Minister, that you are seeing a deputation from the TUC in fifteen minutes, and from the CBI half an hour after that, and the NEB at 12 noon.’

My feeling of despair increased. ‘What do they all want – roughly?’ I asked.

‘They are all worried about the machinery for inflation, deflation and reflation,’ Bernard informed me. What do they think I am? A Minister of the Crown or a bicycle pump?

I indicated the in-tray. ‘When am I going to get through all this correspondence?’ I asked Bernard wearily.

Bernard said: ‘You

do

realise, Minister, that you don’t actually

have

to?’

do

realise, Minister, that you don’t actually

have

to?’

I had realised no such thing. This sounded good.

Bernard continued: ‘If you want, we can simply draft an official reply to any letter.’

‘What’s an official reply?’ I wanted to know.

‘It just says,’ Bernard explained, ‘“the Minister has asked me to thank you for your letter.” Then

we

reply. Something like: “The matter is under consideration.” Or even, if we feel so inclined, “under active consideration!”’

we

reply. Something like: “The matter is under consideration.” Or even, if we feel so inclined, “under active consideration!”’

‘What’s the difference between “under consideration” and “under active consideration”?’ I asked.

‘“Under consideration” means we’ve lost the file. “Under active consideration” means we’re trying to find it!’

I think this might have been one of Bernard’s little jokes. But I’m not absolutely certain.

Bernard was eager to tell me what I had to do in order to lighten the load of my correspondence. ‘You just transfer every letter from your in-tray to your out-tray. You put a brief note in the margin if you want to see the reply. If you don’t, you need never see or hear of it again.’

I was stunned. My secretary was sitting there, seriously telling me that if I move a pile of unanswered letters from one side of my desk to the other, that is all I have to do? [

Crossman had a similar proposition offered, in his first weeks in office – Ed

.]

Crossman had a similar proposition offered, in his first weeks in office – Ed

.]

So I asked Bernard: ‘Then what is the Minister for?’

‘To make policy decisions,’ he replied fluently. ‘When you have decided the policy, we can carry it out.’

It seems to me that if I do not read the letters I will be somewhat ill-informed, and that therefore the number of so-called policy decisions will be reduced to a minimum.

Worse: I would not

know

which were the decisions that I needed to take. I would be dependent on my officials to tell me. I suspect that there would not be very many decisions left.

know

which were the decisions that I needed to take. I would be dependent on my officials to tell me. I suspect that there would not be very many decisions left.

So I asked Bernard: ‘How often are policy decisions needed?’

Bernard hesitated. ‘Well . . . from time to time, Minister,’ he replied in a kindly way.

It is never too soon to get tough. I decided to start in the Department the way I meant to continue. ‘Bernard,’ I said firmly, ‘

this

government governs. It does not just preside like our predecessors did. When a nation’s been going downhill you need someone to get into the driving seat, and put his foot on the accelerator.’

this

government governs. It does not just preside like our predecessors did. When a nation’s been going downhill you need someone to get into the driving seat, and put his foot on the accelerator.’

‘I think perhaps you mean the brake, Minister,’ said Bernard.

I simply do not know whether this earnest young man is being helpful, or is putting me down.

November 11th

Today I saw Sir Humphrey Appleby again. Haven’t seen him for a couple of days now.

There was a meeting in my office about the official visit to the UK of the President of Buranda. I had never even heard of Buranda.

Bernard gave me the brief last night. I found it in the third red box. But I’d had very little time to study it. I asked Humphrey to tell me about Buranda – like, where is it?

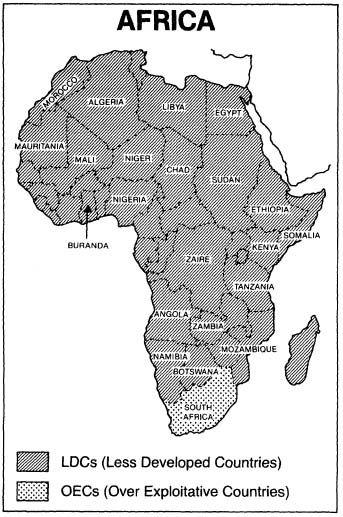

‘It’s fairly new, Minister. It used to be called British Equatorial Africa. It’s the red bit a few inches below the Mediterranean.’

I can’t see what Buranda has got to do with us. Surely this is an FCO job. [

Foreign and Commonwealth Office – Ed

.] But it was explained to me that there was an administrative problem because Her Majesty is due to be up at Balmoral when the President arrives. Therefore she will have to come to London.

Foreign and Commonwealth Office – Ed

.] But it was explained to me that there was an administrative problem because Her Majesty is due to be up at Balmoral when the President arrives. Therefore she will have to come to London.

This surprised me. I’d always thought that State Visits were arranged years in advance. I said so.

‘This is not a State Visit,’ said Sir Humphrey. ‘It is a Head of Government visit.’

I asked if the President of Buranda isn’t the Head of State? Sir Humphrey said that indeed he was, but also the Head of Government.

I said that, if he’s merely coming as Head of Government, I didn’t see why the Queen had to greet him. Humphrey said that it was because

she

is the Head of State. I couldn’t see the logic. Humphrey says that the Head of State must greet a Head of State, even if the visiting Head of State is not

here

as a Head of State but only as a Head of Government.

she

is the Head of State. I couldn’t see the logic. Humphrey says that the Head of State must greet a Head of State, even if the visiting Head of State is not

here

as a Head of State but only as a Head of Government.

Then Bernard decided to explain. ‘It’s all a matter of hats,’ he said.

‘Hats?’ I was becoming even more confused.

‘Yes,’ said Bernard, ‘he’s coming here wearing his Head of Government hat. He is the Head of State, too, but it’s not a State Visit because he’s not wearing his Head of State hat, but protocol demands that even though he is wearing his Head of Government hat, he must still be met by . . .’ I could see his desperate attempt to avoid either mixing metaphors or abandoning his elaborately constructed simile. ‘. . . the Crown,’ he finished in triumph, having thought of the ultimate hat.

I said that I’d never heard of Buranda anyway, and I didn’t know why we were bothering with an official visit from this tin-pot little African country. Sir Humphrey Appleby and Bernard Woolley went visibly pale. I looked at their faces, frozen in horror.

‘Minister,’ said Humphrey, ‘I beg you not to refer to it as a tin-pot African country. It is an LDC.’

LDC is a new one on me. It seems that Buranda is what used to be called an Underdeveloped Country. However, this term has apparently become offensive, so then they were called Developing Countries. This term apparently was patronising. Then they became Less Developed Countries – or LDC, for short.

Sir Humphrey tells me that I

must

be clear on my African terminology, or else I could do irreparable damage.

must

be clear on my African terminology, or else I could do irreparable damage.

It seems, in a nutshell, that the term Less Developed Countries is not yet causing offence to anyone. When it does, we are immediately ready to replace the term LDC with HRRC. This is short for Human Resource-Rich Countries. In other words, they are grossly overpopulated and begging for money. However, Buranda is

not

an HRRC. Nor is it one of the ‘Haves’ or ‘Have-not’ nations – apparently we no longer use those terms either, we talk about the North/South dialogue instead. In fact it seems that Buranda is a ‘will have’ nation, if there were such a term, and if it were not to cause offence to our Afro-Asian, or Third-World, or Non-Aligned-Nation brothers.

not

an HRRC. Nor is it one of the ‘Haves’ or ‘Have-not’ nations – apparently we no longer use those terms either, we talk about the North/South dialogue instead. In fact it seems that Buranda is a ‘will have’ nation, if there were such a term, and if it were not to cause offence to our Afro-Asian, or Third-World, or Non-Aligned-Nation brothers.

‘Buranda

will have

a huge amount of oil in a couple of years from now,’ confided Sir Humphrey.

will have

a huge amount of oil in a couple of years from now,’ confided Sir Humphrey.

‘Oh I see,’ I said. ‘So it’s not a TPLAC at all.’

Sir Humphrey was baffled. It gave me pleasure to baffle him for once. ‘TPLAC?’ he enquired carefully.

‘Tin-Pot Little African Country,’ I explained.

Sir Humphrey and Bernard jumped. They looked profoundly shocked. They glanced nervously around to check that I’d not been overheard. They were certainly not amused. How silly – anyone would think my office was bugged! [

Perhaps it was – Ed

.]

Perhaps it was – Ed

.]

Other books

The Lost Wife by Alyson Richman

The Year We Disappeared by Busby, Cylin

A Man Overboard by Hopkins, Shawn

Deathstalker by Green, Simon R.

Creative People Must Be Stopped by David A Owens

Rodin's Lover by Heather Webb

Running With the Pack by Ekaterina Sedia

Moving Forward by Hooper, Sara

The Field by John B. Keane

The Tenth Legion (Book 6, Progeny of Evolution) by Mike Arsuaga