The Complete Yes Minister (12 page)

Sir Humphrey obliged. ‘Minister . . . if we were to end the economy drive and close the Bureaucratic Watchdog Office we could issue an immediate press announcement that you had axed eight hundred jobs.’ He had obviously thought this out carefully in advance, for at this moment he produced a slim folder from under his arm. ‘If you’d like to approve this draft. . . .’

I couldn’t believe the impertinence of the suggestion. Axed eight hundred jobs? ‘But no one was ever doing these jobs,’ I pointed out incredulously. ‘No one’s been appointed yet.’

‘Even greater economy,’ he replied instantly. ‘We’ve saved eight hundred redundancy payments as well.’

‘But . . .’ I attempted to explain ‘. . . that’s just phony. It’s dishonest, it’s juggling with figures, it’s pulling the wool over people’s eyes.’

‘A government press release, in fact,’ said Humphrey. I’ve met some cynical politicians in my time, but this remark from my Permanent Secretary was a real eye-opener.

I nodded weakly. Clearly if I was to avoid the calamity of four hundred new people employed to make economies, I had to give up the four hundred new people in my cherished Watchdog Office. An inevitable

quid pro quo

. After all, politics is the art of the possible. [

A saying generally attributed to R. A. Butler, but actually said by Bismarck (1815–98) in 1867, in conversation with Meyer von Waldeck: ‘Die Politik ist die Lehre von Möglichen’ – Ed

.]

quid pro quo

. After all, politics is the art of the possible. [

A saying generally attributed to R. A. Butler, but actually said by Bismarck (1815–98) in 1867, in conversation with Meyer von Waldeck: ‘Die Politik ist die Lehre von Möglichen’ – Ed

.]

However, one vital central question, the question that was at the root of this whole débâcle, remained completely unanswered. ‘But Humphrey,’ I said. ‘How are we actually going to slim down the Civil Service?’

There was a pause. Then he said: ‘Well . . . I suppose we could lose one or two of the tea ladies.’

1

The Bureaucratic Watchdog was an innovation of Hacker’s, to which members of the public were invited to report any instances of excessive government bureaucracy which they encountered personally. It was disbanded after four months.

The Bureaucratic Watchdog was an innovation of Hacker’s, to which members of the public were invited to report any instances of excessive government bureaucracy which they encountered personally. It was disbanded after four months.

2

In conversation with the Editors.

In conversation with the Editors.

4

Big Brother

January 4th

Nothing of interest happened over Christmas. I spent the week in the constituency. I went to the usual Christmas parties for the constituency party, the old people’s home, the general hospital, and assorted other gatherings and it all went off quite well – I got my photo in the local rag four or five times, and avoided saying anything that committed me to anything.

I sensed a sort of resentment, though, and have become aware that I’m in a double-bind situation. The local party, the constituency, my family,

all

of them are proud of me for getting into the Cabinet – yet they are all resentful that I have less time to spend on them and are keen to remind me that I’m nothing special, just their local MP, and that I mustn’t get ‘too big for my boots’. They manage both to grovel and patronise me simultaneously. It’s hard to know how to handle it.

all

of them are proud of me for getting into the Cabinet – yet they are all resentful that I have less time to spend on them and are keen to remind me that I’m nothing special, just their local MP, and that I mustn’t get ‘too big for my boots’. They manage both to grovel and patronise me simultaneously. It’s hard to know how to handle it.

If only I could tell them what life is really like in Whitehall, they would know that there’s absolutely no danger of my getting too big for my boots. Sir Humphrey Appleby will see to that.

Back to London today for a TV interview on

Topic

, with Robert McKenzie. He asked me lots of awkward questions about the National Data Base.

Topic

, with Robert McKenzie. He asked me lots of awkward questions about the National Data Base.

We met in the Hospitality Room before the programme was recorded, and I tried to find out what angle he was taking. We were a little tense with each other, of course. [

McKenzie used to call the Hospitality Room the Hostility Room – Ed

.]

McKenzie used to call the Hospitality Room the Hostility Room – Ed

.]

‘We are going to talk about cutting government extravagance and that sort of thing, aren’t we?’ I asked, and immediately realised that I had phrased that rather badly.

Bob McKenzie was amused. ‘You want to talk about the government’s extravagance?’ he said with a twinkle in his eye.

‘About the ways in which I’m cutting it down, I mean,’ I said firmly.

‘We’ll get to that if we have time after the National Data Base,’ he said.

I tried to persuade him that people weren’t interested in the Data Base, that it was too trivial. He said he thought people were

very

interested in it, and were worried about Big Brother. This annoyed me, and I told him he couldn’t trivialise the National Data Base with that sort of sensationalistic approach. Bob replied that as I’d just said it was trivial already, why not?

very

interested in it, and were worried about Big Brother. This annoyed me, and I told him he couldn’t trivialise the National Data Base with that sort of sensationalistic approach. Bob replied that as I’d just said it was trivial already, why not?

We left the Hospitality Room. In the studio, waiting for the programme to begin, a girl with a powder-puff kept flitting about and dabbing at my face and preventing me from thinking straight. She said I was getting a bit pink. ‘We can’t have that,’ said Bob jovially, ‘what would the

Daily Telegraph

say?’

Daily Telegraph

say?’

Just before we started recording I remarked that I could well do without all those old chestnut questions like, ‘Are we creating a Police State?’

In retrospect, perhaps this was a mistake.

[

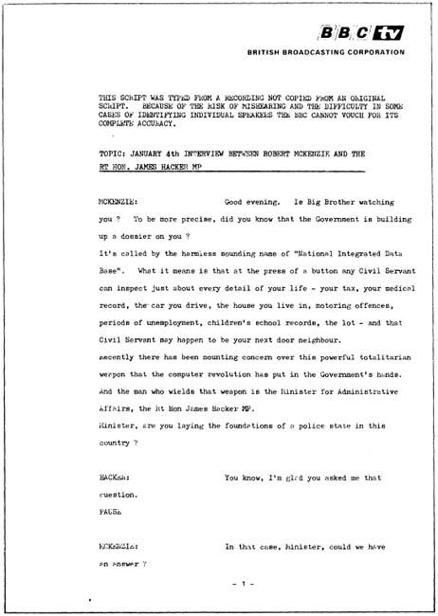

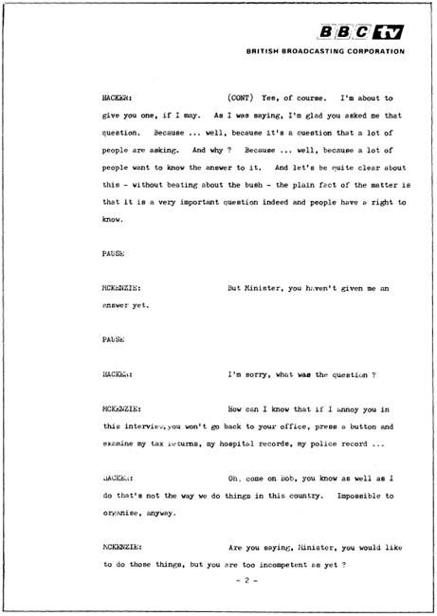

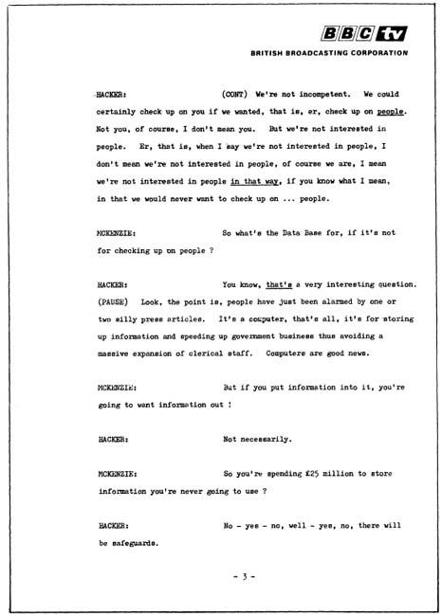

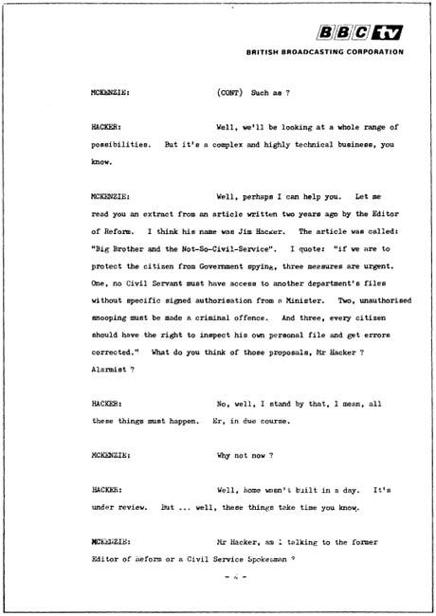

We have found, in the BBC Archives, a complete transcript of Robert McKenzie’s interview with James Hacker. It is printed below – Ed

.]

We have found, in the BBC Archives, a complete transcript of Robert McKenzie’s interview with James Hacker. It is printed below – Ed

.]

I thought I’d waffled a bit, but Bob told me I’d stonewalled beautifully. We went back to Hospitality for another New Year’s drink. I congratulated him on finding that old article of mine – a crafty move. He said that one of his research girls had found it, and asked if I wanted to meet her. I declined – and said I’d just go back to my office and have a look at her dossier!

I watched the programme in the evening. I think it was okay. I hope Sir Humphrey is pleased, anyway.

January 7th

There was divided opinion in the office this afternoon about my TV appearance three days ago. The matter came up at a 4 p.m. meeting with Sir Humphrey, Bernard and Frank Weisel.

Humphrey and Bernard thought I’d been splendid. Dignified and suitable. But Frank’s voice was particularly notable by its silence, during this chorus of praise. When I asked him what he thought, he just snorted like a horse. I asked him to translate.

He didn’t answer me, but turned to Sir Humphrey. ‘I congratulate you,’ he began, his manner even a little less charming than usual. ‘Jim is now perfectly house-trained.’ Humphrey attempted to excuse himself and leave the room.

‘If you’ll excuse me, Mr Weasel . . .’

‘Weisel!’ snapped Frank. He turned on me. ‘Do you realise you just say everything the Civil Service programmes you to say. What are you, a man or a mouth?’

Nobody laughed at his little pun.

‘It may be very hard for a political adviser to understand,’ said Sir Humphrey, in his most patronising manner, ‘but I am merely a civil servant and I just do as I am instructed by my master.’

Frank fumed away, muttering, ‘your master, typical stupid bloody phrase, public school nonsense,’ and so forth. I must say, the phrase interested me too.

‘What happens,’ I asked, ‘if the Minister is a woman? What do you call her?’

Humphrey was immediately in his element. He loves answering questions about good form and protocol. ‘Yes, that’s most interesting. We sought an answer to the point when I was a Principal Private Secretary and Dr Edith Summerskill was appointed Minister in 1947. I didn’t quite like to refer to her as my mistress.’

He paused. For effect, I thought at first, but then he appeared to have more to say on the subject.

‘What was the answer?’ I asked.

‘We’re still waiting for it,’ he explained.

Frank chipped in with a little of his heavy-duty irony. ‘It’s under review is it? Rome wasn’t built in a day, eh Sir Humphrey? These things take time, do they?’

Frank is actually beginning to get on my nerves. The chip on his shoulder about the Civil Service is getting larger every day. I don’t know why, because they have given him an office, he has free access to me, and they tell me that they give him all possible papers that would be of use to him. Now he’s started to take out his aggressions on me. He’s like a bear with a sore head. Perhaps he’s still getting over his New Year’s hangover.

Humphrey wanted to leave, so did I, but Bernard started to give me my diary appointments – and that started another wrangle. Bernard told me I was to meet him at Paddington at 8 a.m. tomorrow, because I was to speak at the Luncheon of the Conference of Municipal Treasurers at the Vehicle Licensing Centre in Swansea. Frank then reminded me that I was due in Newcastle tomorrow night to address the by-election meeting. Bernard pointed out to me that I couldn’t do both and I explained this to Frank. Frank pointed out that the by-election was important to us, whereas the Swansea trip was just a Civil Service junket, and I explained this to Bernard. Bernard then reminded me that the Conference had been in my diary for some time and that they all expected me to go to Swansea, and I explained this to Frank and then Frank reminded me that Central House [

the party headquarters – Ed

.] expected me to go to Newcastle, but I didn’t explain this to Bernard because by this time I was tired of explaining and I said so. So Frank asked Bernard to explain why I was double booked, Bernard said no one had told him about Newcastle, I asked Frank why he hadn’t told Bernard, Frank asked me why

I

hadn’t told Bernard, and I pointed out that I couldn’t remember everything.

the party headquarters – Ed

.] expected me to go to Newcastle, but I didn’t explain this to Bernard because by this time I was tired of explaining and I said so. So Frank asked Bernard to explain why I was double booked, Bernard said no one had told him about Newcastle, I asked Frank why he hadn’t told Bernard, Frank asked me why

I

hadn’t told Bernard, and I pointed out that I couldn’t remember everything.

Other books

Nicole: Star Crossed Lovers (A Wish for Love Series Book 2) by Shales, Mia

Una bandera tachonada de estrellas by Brad Ferguson

Jaci Burton by Playing to Win

Mistress Shakespeare by Karen Harper

Shadow Hunters by Christie Golden

Bound by the Vampire Queen by Joey W. Hill

Billionaire's Pet 2 (BDSM, Domination and Submission Erotic Romance) by Wick, Christa

Chesapeake Blue by Nora Roberts

Single Combat by Dean Ing

Guardian of My Soul by Elizabeth Lapthorne