The Complete Yes Minister (6 page)

November 12th

On my way to work this morning I had an inspiration.

At my meeting with Humphrey yesterday it had been left for him to make arrangements to get the Queen down from Balmoral to meet the Burandan President. But this morning I remembered that we have three by-elections pending in three marginal Scottish constituencies, as a result of the death of one member who was so surprised that his constituents re-elected him in spite of his corruption and dishonesty that he had a heart attack and died, and as a result of the elevation of two other members to the Lords on the formation of the new government. [

The Peerage and/or the heart attack are, of course, the two most usual rewards for a career of corruption and dishonesty – Ed

.]

The Peerage and/or the heart attack are, of course, the two most usual rewards for a career of corruption and dishonesty – Ed

.]

I called Humphrey to my office. ‘The Queen,’ I announced, ‘does not have to come down from Balmoral at all.’

There was a slight pause.

‘Are you proposing,’ said Sir Humphrey in a pained manner, ‘that Her Majesty and the President should exchange official greetings by telephone?’

‘No.’

‘Then,’ said Sir Humphrey, even more pained, ‘perhaps you just want them to shout very loudly.’

‘Not that either,’ I said cheerfully. ‘We will hold the official visit in Scotland. Holyrood Palace.’

Sir Humphrey replied instantly. ‘Out of the question,’ he said.

‘Humphrey,’ I said. ‘Are you sure you’ve given this idea due consideration?’

‘It’s not our decision,’ he replied. ‘It’s an FCO matter.’

I was ready for this. I spent last night studying that wretched document which had caused me so much trouble yesterday. ‘I don’t think so,’ I said, and produced the file with a fine flourish. ‘Notwithstanding the provisions of subsection 3 blah blah blah . . . administrative procedures blah blah blah . . . shall fall within the purview of the Minister for Administrative Affairs.’ I sat back and watched.

Sir Humphrey was stumped. ‘Yes, but . . . why do you want to do this?’ he asked.

‘It saves Her Majesty a pointless journey. And there are three marginal Scottish by-elections coming up. We’ll hold them as soon as the visit is over.’

He suddenly went rather cool. ‘Minister, we do not hold Head of Government visits for party political reasons, but for reasons of State.’

He had a point there. I’d slipped up a bit, but I managed to justify it okay. ‘But my plan really shows that Scotland is an equal partner in the United Kingdom. She

is

Queen of Scotland too. And Scotland is full of marginal constit . . .’ I stopped myself just in time, I think, ‘. . . depressed areas.’

is

Queen of Scotland too. And Scotland is full of marginal constit . . .’ I stopped myself just in time, I think, ‘. . . depressed areas.’

But Sir Humphrey was clearly hostile to the whole brilliant notion. ‘I hardly think, Minister,’ he sneered, clambering onto his highest horse and looking down his patrician nose at me, ‘I hardly think we can exploit our Sovereign by involving her in, if you will forgive the phrase, a squalid vote-grubbing exercise.’

I don’t think there’s anything squalid about grubbing for votes. I’m a democrat and proud of it and that’s what democracy is all about! But I could see that I had to think up a better reason (for Civil Service consumption, at least) or else this excellent plan would be blocked somehow. So I asked Humphrey why the President of Buranda was coming to Britain.

‘For an exchange of views on matters of mutual interest,’ was the reply. Why does this man insist on speaking in the language of official communiqués? Or can’t he help it?

‘Now tell me why he’s coming,’ I asked with exaggerated patience. I was prepared to keep asking until I got the real answer.

‘He’s here to place a huge order with the British Government for offshore drilling equipment.’

Perfect! I went in for the kill. ‘And where can he see all our offshore equipment? Aberdeen, Clydeside.’

Sir Humphrey tried to argue. ‘Yes, but . . .’

‘How many oil rigs have you got in Haslemere, Humphrey?’ He wasn’t pleased by this question.

‘But the administrative problems . . .’ he began.

I interrupted grandly: ‘Administrative problems are what this whole Department was created to solve. I’m sure you can do it, Humphrey.’

‘But Scotland’s so remote.’ He was whining and complaining now. I knew I’d got him on the run. ‘Not all that remote,’ I said, and pointed to the map of the UK hanging on the wall. ‘It’s that pink bit, about two feet above Potters Bar.’

Humphrey was not amused – ‘Very droll, Minister,’ he said. But

even that

did not crush me.

even that

did not crush me.

‘It is going to be Scotland,’ I said with finality. ‘That is my

policy

decision. That’s what I’m here for, right Bernard?’

policy

decision. That’s what I’m here for, right Bernard?’

Bernard didn’t want to take sides against Humphrey, or against me. He was stuck. ‘Um . . .’ he said.

I dismissed Humphrey, and told him to get on with making the arrangements. He stalked out of my office. Bernard’s eyes remained glued to the floor.

Bernard is

my

Private Secretary and, as such, is apparently supposed to be on my side. On the other hand, his future lies with the Department which means that he has to be on Humphrey’s side. I don’t see how he can possibly be on both sides. Yet, apparently, only if he succeeds in this task that is, by definition, impossible, will he continue his rapid rise to the top. It’s all very puzzling. I must try and find out if I can trust him.

my

Private Secretary and, as such, is apparently supposed to be on my side. On the other hand, his future lies with the Department which means that he has to be on Humphrey’s side. I don’t see how he can possibly be on both sides. Yet, apparently, only if he succeeds in this task that is, by definition, impossible, will he continue his rapid rise to the top. It’s all very puzzling. I must try and find out if I can trust him.

November 13th

Had a little chat with Bernard on our way back from Cardiff, where I addressed a conference of Municipal Treasurers and Chief Executives.

Bernard warned me that Humphrey’s next move, over this Scottish business, would be to set up an interdepartmental committee to investigate and report.

I regard the interdepartmental committee as the last refuge of a desperate bureaucrat. When you can’t find any argument against something you don’t want, you set up an interdepartmental committee to strangle it. Slowly. I said so to Bernard. He agreed.

‘It’s for the same reason that politicians set up Royal Commissions,’ said Bernard. I began to see why he’s a high-flyer.

I decided to ask Bernard what Humphrey

really

had against the idea.

really

had against the idea.

‘The point is,’ Bernard explained, ‘once they’re all in Scotland the whole visit will fall within the purview of the Secretary of State for Scotland.’

I remarked that Humphrey should be pleased by this. Less work.

Bernard put me right on that immediately. Apparently the problem is that Sir Humphrey likes to go to the Palace, all dressed up in his white tie and tails and medals. But in Scotland the whole thing will be on a much smaller scale. Not so many receptions and dinners. Not so many for Sir Humphrey, anyway, only for the Perm. Sec. at the Scottish Office. Sir Humphrey might not even be invited to the return dinner, as the Burandan Consulate in Edinburgh is probably exceedingly small.

I had never given the ceremonial aspect of all this any thought at all. But according to Bernard all the glitter is frightfully important to Permanent Secretaries. I asked Bernard if Humphrey had lots of medals to wear.

‘Quite a few,’ Bernard told me. ‘Of course he got his K a long time ago. He’s a KCB. But there are rumours that he might get his G in the next Honours list.’

1

1

‘How did you hear that?’ I asked. I thought Honours were always a big secret.

‘I heard it on the grapevine,’ said Bernard.

I suppose, if Humphrey doesn’t get his G, we’ll hear about it on the sour-grapevine.

[

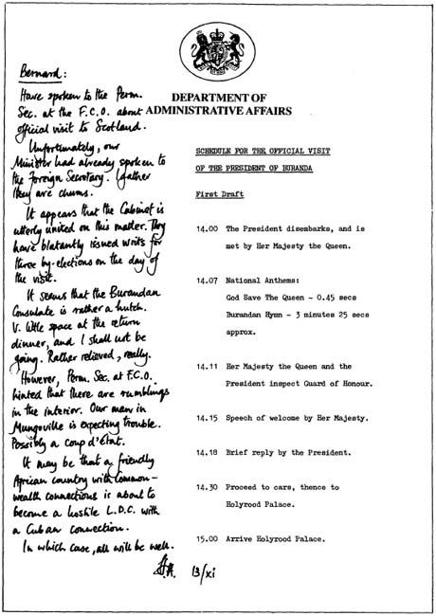

Shortly after this conversation a note was sent by Sir Humphrey to Bernard Woolley. As usual Sir Humphrey wrote in the margin – Ed

.]

Shortly after this conversation a note was sent by Sir Humphrey to Bernard Woolley. As usual Sir Humphrey wrote in the margin – Ed

.]

[

Presumably by ‘all will be well’ Sir Humphrey was referring to the cancellation of the official visit, rather than another Central African country going communist – Ed

.]

Presumably by ‘all will be well’ Sir Humphrey was referring to the cancellation of the official visit, rather than another Central African country going communist – Ed

.]

November 18th

Long lapse since I made any entries in the diary. Partly due to the weekend, which was taken up with boring constituency business. And partly due to pressure of work – boring Ministerial business.

I feel that work is being kept from me. Not that I’m short of work. My boxes are full of irrelevant and unimportant rubbish.

Yesterday I really had nothing to do at all in the afternoon. No engagements of any sort. Bernard was forced to advise me to go to the House of Commons and listen to the debate there. I’ve never heard such a ridiculous suggestion.

Late this afternoon I was in the office, going over the plans for the Burandan visit, and I switched on the TV news. To my horror they reported a

coup d’état

in Buranda. Marxist, they think. They reported widespread international interest and concern because of Buranda’s oil reserves. It seems that the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces, who rejoices in the name of Colonel Selim Mohammed, has been declared President. Or has declared himself President, more likely. And no one knows what has happened to the former President.

coup d’état

in Buranda. Marxist, they think. They reported widespread international interest and concern because of Buranda’s oil reserves. It seems that the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces, who rejoices in the name of Colonel Selim Mohammed, has been declared President. Or has declared himself President, more likely. And no one knows what has happened to the former President.

I was appalled. Bernard was with me, and I told him to get me the Foreign Secretary at once.

‘Shall we scramble?’ he said.

‘Where to?’ I said, then felt rather foolish as I realised what he was talking about. Then I realised it was another of Bernard’s daft suggestions: what’s the point of scrambling a phone conversation about something that’s just been on the television news?

I got through to Martin at the Foreign Office.

Incredibly, he knew nothing about the coup in Buranda.

‘How do you know?’ he asked when I told him.

‘It’s on TV. Didn’t you know? You’re the Foreign Secretary, for God’s sake.’

‘Yes,’ said Martin, ‘but my TV set’s broken.’

I could hardly believe my ears. ‘Your TV set? Don’t you get the Foreign Office telegrams?’

Martin said: ‘Yes, but they don’t come in till much later. A couple of days, maybe. I always get the Foreign News from the telly.’

I thought he was joking. It seems he was not. I said that we must make sure that the official visit was still on, come what may. There are three by-elections hanging on it. He agreed.

I rang off, but not before telling Martin to let me know if he heard any more details.

‘No, you let

me

know,’ Martin said. ‘You’re the one with the TV set.’

me

know,’ Martin said. ‘You’re the one with the TV set.’

November 19th

Meeting with Sir Humphrey first thing this morning. He was very jovial, beaming almost from ear to ear.

‘You’ve heard the sad news, Minister?’ he began, smiling broadly.

I nodded.

‘It’s just a slight inconvenience,’ he went on, and made a rotary gesture with both hands. ‘The wheels are in motion, it’s really quite simple to cancel the arrangements for the visit.’

‘You’ll do no such thing,’ I told him.

‘But Minister, we have no choice.’

‘We have,’ I countered. ‘I’ve spoken to the Foreign Secretary already.’ His face seemed to twitch a bit. ‘We are reissuing the invitation to the new President.’

‘New President?’ Humphrey was aghast. ‘But we haven’t even recognised his government.’

I made the same rotary gesture with my hands. ‘The wheels are in motion,’ I smiled. I was enjoying myself at last.

Humphrey said: ‘We don’t know who he is.’

‘Somebody Mohammed,’ I explained.

‘But . . . we don’t know anything about him. What’s he like?’

I pointed out, rather wittily I thought, that we were not considering him for membership of the Athenaeum Club. I said that I didn’t give a stuff what he was like.

Sir Humphrey tried to get tough. ‘Minister,’ he began, ‘there is total confusion in Buranda. We don’t know who is behind him. We don’t know if he’s Soviet-backed, or just an ordinary Burandan who’s gone berserk. We cannot take diplomatic risks.’

‘The government has no choice,’ I said.

Sir Humphrey tried a new tack. ‘We have not done the paperwork.’ I ignored this rubbish. Paperwork is the religion of the Civil Service. I can just imagine Sir Humphrey Appleby on his deathbed, surrounded by wills and insurance claim forms, looking up and saying, ‘I cannot go yet, God, I haven’t done the paperwork.’

Sir Humphrey pressed on. ‘The Palace insists that Her Majesty be properly briefed. This is not possible without the paperwork.’

I stood up. ‘Her Majesty will cope. She always does.’ Now I had put him in the position of having to criticise Her Majesty.

He handled it well. He stood up too. ‘Out of the question,’ he replied. ‘Who

is

he? He might not be properly brought up. He might be rude to her. He might . . . take liberties!’ The mind boggles. ‘And he is bound to be photographed with Her Majesty – what if he then turns out to be another Idi Amin? The repercussions are too hideous to contemplate.’

is

he? He might not be properly brought up. He might be rude to her. He might . . . take liberties!’ The mind boggles. ‘And he is bound to be photographed with Her Majesty – what if he then turns out to be another Idi Amin? The repercussions are too hideous to contemplate.’

I must say the last point does slightly worry me. But not as much as throwing away three marginals. I spelt out the contrary arguments to Humphrey. ‘There are reasons of State,’ I said, ‘which make this visit essential. Buranda is potentially enormously rich. It needs oil rigs. We have idle shipyards on the Clyde. Moreover, Buranda is strategically vital to the government’s African policy.’

Other books

Kindling Flames: Smoke Rising (The Ancient Fire Series Book 3) by Julie Wetzel

Touch to Surrender by Cara Dee

The Dark Ones by Smith, Bryan

Death Dance by Linda Fairstein

Challenge to Him by Lisabet Sarai

Partners by Contract by Kim Lawrence

Mourning Cloak by Gale, Rabia

Yalo by Elias Khoury

Need You for Mine (Heroes of St. Helena) by Marina Adair

Midnight Sun by M J Fredrick