The Books of Elsewhere, Vol. 1: The Shadows (2 page)

Read The Books of Elsewhere, Vol. 1: The Shadows Online

Authors: Jacqueline West

BOOK: The Books of Elsewhere, Vol. 1: The Shadows

7.23Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

“The managers of the estate have decided to sell the contents along with the house. Of course, you can dispose of these however you choose,” said Mr. Hambert consolingly, as though so many books would be a terrible bother.

“This room would be just perfect for studying, correcting papers, writing articles . . . don’t you think?” said Mrs. Dunwoody to Mr. Dunwoody dreamily.

“Oh, yes, very cozy,” agreed Mr. Dunwoody. “You know, I don’t believe that we need more time to make up our minds—do you, dear?”

Mr. and Mrs. Dunwoody exchanged another misty look. Then Mr. Dunwoody declared, “We’ll take it.”

Mr. Hambert’s face turned as red as a new potato. He burbled and shone and shook Mr. Dunwoody’s hand, then Mrs. Dunwoody’s hand, then Mr. Dunwoody’s hand again.

“Excellent! Excellent!” he boomed. “Congratulations—perfect house for a family! So big, so full of history . . . A quick look around the second floor, and we can go back to my office and sign the papers!”

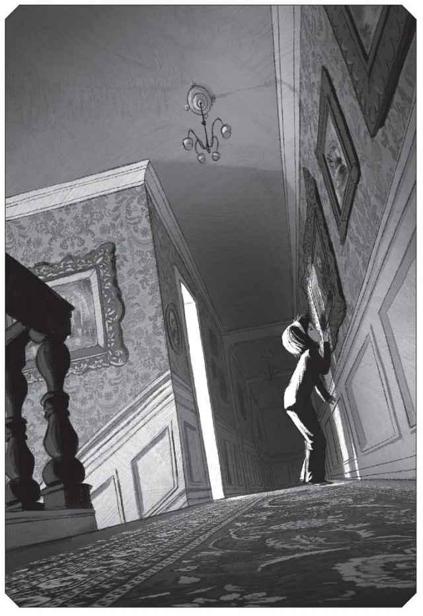

They all trooped up the mossy carpet of the staircase, Mr. Hambert in the lead, puffing happily, Mr. and Mrs. Dunwoody following hand in hand, smiling up at the high ceilings as though some lovely algebraic theorem unfolded there. Olive trailed behind, running her hand up the banister and collecting a pile of thick dust. At the top of the stairs, she rolled the dust into a little ball and blew it off of her palm. It floated slowly down, past the banister, past the old wall sconces, into the dark hallway.

Her parents had disappeared into one of the bedrooms. She could still hear Mr. Hambert shouting “Excellent! Excellent!” every now and again.

Olive stood by herself on the landing and felt the big stone house loom around her.

This is our house

, she told herself, just to see how it felt.

Our house.

The words hovered in her mind like candle smoke. Before Olive could quite believe them, they had faded away.

This is our house

, she told herself, just to see how it felt.

Our house.

The words hovered in her mind like candle smoke. Before Olive could quite believe them, they had faded away.

Olive turned in a slow circle. The hall stretched away from her in two directions, dwindling into darkness at both ends. Dim light from one hanging lamp outlined the frames of the pictures on the walls. Behind Olive, at the top of the stairs, was a large painting in a thick gold frame. Olive liked to paint, but she mostly made squiggly designs or imaginary creatures from the books she read. She had never painted anything like this.

Olive peered into the canvas. It was a painting of a forest at night. The twigs of leafless trees made a black web against the sky. A full moon pressed its face through the clouds, touching a path of white stones that led into the dark woods and disappeared. But it seemed to Olive that somewhere—maybe just at the end of that white path, maybe in that darkness where the moonlight couldn’t reach—there was something

else

within that painting. Something she could almost see.

else

within that painting. Something she could almost see.

“Olive?” Mrs. Dunwoody’s head popped through a doorway along the hall. “Don’t you want to see your bedroom?”

Olive walked slowly away from the painting, keeping her eye on it over her shoulder. She would figure it out later, she told herself. She would have plenty of time.

2

T

HE DUNWOODYS MOVED in two weeks later. Everything had been taken out of their two-bedroom apartment and scattered through the stone mansion on Linden Street. In the big old house, their belongings looked small and out of place, like tiny visitors from outer space trying to blend in at a Victorian ball. The Dunwoodys’ expensive computer sat on an old wooden desk in the library, where antique books seemed to look at it a bit distrustfully. There weren’t enough outlets in the kitchen for all of their appliances, but in every drawer and corner they found utensils that no one could figure out—they could have been cooking accessories or dental equipment, for all any of the Dunwoodys knew. Sepia portraits hung from the walls, and glass medicine bottles stood in every bathroom cabinet.

HE DUNWOODYS MOVED in two weeks later. Everything had been taken out of their two-bedroom apartment and scattered through the stone mansion on Linden Street. In the big old house, their belongings looked small and out of place, like tiny visitors from outer space trying to blend in at a Victorian ball. The Dunwoodys’ expensive computer sat on an old wooden desk in the library, where antique books seemed to look at it a bit distrustfully. There weren’t enough outlets in the kitchen for all of their appliances, but in every drawer and corner they found utensils that no one could figure out—they could have been cooking accessories or dental equipment, for all any of the Dunwoodys knew. Sepia portraits hung from the walls, and glass medicine bottles stood in every bathroom cabinet.

In one spare bedroom, Olive discovered an old chest of drawers that was full of handkerchiefs and lacy bloomers, a pair of spectacles, and pearl-buttoned gloves. There were even ropes of fake pearls and colored glass beads that she could try on and pretend to be Cleopatra or Queen Guinevere. Even though Mr. Hambert had said everything in the house was theirs, Olive always carefully wrapped the jewelry and the gloves back up in tissue paper and returned them to the drawers, just as she had found them. It felt right, somehow. It was like being in a museum where you were allowed to play with the exhibits, not just stare at them through the glass.

At the same time, Olive missed their old apartment, where all the beige walls met at perfect ninety-degree angles, where there were no surprising corners, no twisting hallways, no slanted ceilings to bash your forehead against as you climbed out of the bathtub. This new house was always sneaking up on her.

The Dunwoodys had lived in many different apartments, but somehow they all felt the same to Olive. They were all in three-story buildings made of brick, where all the walls were the same color, and all the windows were the same shape, and you could wander into a neighbor’s living room (if their door was unlocked) and spend several minutes lying on their couch, which was exactly like your couch, watching their TV, before you realized you were in the wrong place. Olive had done this quite a few times.

No one would ever mistake the big house on Linden Street for someplace else. This house was crumbly and dark and weird. It was full of corners that the lights never reached. It made squeaking, moaning sounds when the wind changed, like a dog howling or a child whimpering. Olive had never been anywhere—not even the doctor’s office, not even

gym class

—that made her feel so out of place, or so alone.

gym class

—that made her feel so out of place, or so alone.

And the painting at the top of the stairs still seemed to be keeping a secret. Olive stood in front of it for almost half an hour that first night, until her eyes crossed and bits of the trees popped out at her. Nothing. Nothing but the feeling that there was something not quite right about this painting.

And it wasn’t the only one.

There were paintings all over the house that gave her the same funny feeling. Right outside her bedroom door, there was a painting of a rolling field with a row of little houses in the distance. It was evening in the painting, and all the windows in the houses were dark. But the houses didn’t look like they were sleeping comfortably, just waiting for sunrise to come and start another day. The houses looked like they were holding their breath. They crouched among the trees and blew out their lights, trying not to be seen. Seen by what? Olive wondered.

On their first night in the house, Mrs. Dunwoody came upstairs to tuck Olive into bed. Olive heard her mother’s steps on the squeaky staircase and reluctantly pulled her eyes away from the painting. She scurried into her room and hopped under the blankets, knocking several pillows onto the floor.

“Ready for bed, sweetie?” asked Mrs. Dunwoody, peeking in.

“Yes,” said Olive.

“Good girl.” Her mother crossed the room and sat down on the edge of Olive’s high, creaky bed. “Are you comfy?”

“Mm-hm,” answered Olive.

“I know it’s going to take some getting used to, sweetie—this new room, and new house, and new everything. But I bet that in just a few days you’re going to start to feel at home here. Don’t you like having such a big house and big yard to play in?”

“Yeah . . . kind of,” said Olive. “I don’t know.”

“Just give it a little more time. You’ll see.”

Her mother stood up. The mattress bounced just a little. “See you in the morning,” she whispered from the doorway.

“Um—Mom?” said Olive, just as Mrs. Dunwoody was pulling the door closed. “Something here is . . . There’s something . . . bugging me.”

“What is it?” asked her mother.

“That painting, right outside my door? It bothers me. It’s . . . creepy.”

Olive slid back out of bed and padded into the hallway, where her mother stood, frowning up at the painting.

“This one, of the little town?” said Mrs. Dunwoody doubtfully. “What do you think is creepy about it?”

“It looks . . .” Olive whispered, feeling silly. “I think it looks scared. It’s like the houses are trying to pretend they’re asleep, and stay quiet . . . like something bad is coming.”

“Hmmm,” said her mother, trying to hide the skeptical look on her face. “Well, why don’t we just take it down?”

Mrs. Dunwoody grabbed the sides of the thick wooden frame and pulled. But the painting didn’t budge.

“That’s funny,” she said.

She tried pushing the frame upward, in case the painting was hung on a hook. Still it didn’t move.

“This is very strange,” Mrs. Dunwoody said.

Bracing her feet on the hallway carpet, Mrs. Dunwoody got a good grip on the bottom corners of the frame and yanked as hard as she could. Olive thought the frame would either crack in half or her mother would lose her hold on it and go flying backward across the hall. But neither thing happened.

“Oof,” puffed Mrs. Dunwoody. “It’s really stuck. It must be glued to the wall or something . . . or over time, the wallpaper has bonded to the back of the canvas. Maybe if it got wet . . .” Mrs. Dunwoody trailed off, silently calculating various hypotheses.

“Let’s worry about it tomorrow. For now,” she said, guiding Olive back into the bedroom, “let’s get you tucked in again.”

Her mother tugged the covers up under Olive’s chin and smoothed the wrinkles around her feet. “Where’s Hershel?” she asked.

“Right here,” said Olive, holding up the worn brown teddy bear.

“Good. He’ll protect you,” said Mrs. Dunwoody, heading back toward the door. “But I’ll leave the hall light on, just in case.”

The door clicked shut behind her mother. Olive lay very still, wide-awake, listening to her mother’s footsteps fade away down the hall. Then she swung her legs carefully out of bed, making the bedspread rustle as little as possible.

Olive peeped out the door and looked down the hallway in both directions. Her parents were closed inside their bedroom. The hall lamp sent a soft glow over the thick carpet and made the polished wood along the walls glint like brass. She tiptoed out and stood in front of the painting. The row of houses cowered on their twilit street. Olive grabbed the frame. She pulled and pulled and pulled, but the painting wouldn’t move. It felt almost like the painting was part of the wall itself.

Olive walked quietly along the hall toward the stairs, looking carefully at the other paintings. They seemed even stranger in the dim light than they had earlier in the day. One showed a big bowl of fruit, but they were fruits Olive had never seen in any grocery store. They were funnily shaped and strangely colored, and a few of them were sliced open to show bright pink or green centers with glistening seeds. Another painting depicted a rocky, treeless hill and a crumbling stone church, far away in the background. She hadn’t noticed it before, but when she squinted and leaned very close, Olive thought that she could make out the bumps and crosses of distant gravestones.

Just to check, she yanked on the frame of each painting. None of them budged. She was just reaching the head of the stairs when something to the left caught her eye. In the big painting of the moonlight and the forest, something had changed.

At first Olive thought that the light looked different, as if the painted moon itself had moved. But no—the moon hung just where it had before, behind the leafless trees. It was something about the shadows. Olive moved closer, watching. The shadows suddenly rippled and bent, and within the shadows, a pale splotch darted out of the undergrowth. Olive froze, staring at the white path. She blinked, rubbed her eyelids with her fingertips, and looked again. Yes—there it was. Something was moving inside the painting, a tiny white shape flitting between the silhouettes of the wiry trees. Olive held perfectly still. She didn’t even breathe. The tiny white shape made one more quick plunge toward the path, then dove back into the thorny black forest. And then the painting, too, was perfectly still.

Olive bolted back to her bedroom, jumped into the bed, and yanked the covers over her face. Then she lay as still as she could and listened. The house’s creaks and groans were almost covered by the thumps of her own heart. But not quite.

In every place that Olive’s family had lived, there had been other people nearby. On the other side of the apartment walls, neighbors moved around in their matching sets of rooms, talking, eating, going about their own lives. Even if Olive couldn’t hear them, even if she had rarely spoken to them, she knew they were there. Here, it was just Olive and her parents . . . and whatever it was that flitted through the shadows on that painted forest path.

Other books

Sand Angel by Mackenzie McKade

Death's Mantle: An Urban Fantasy Novel (Revelations Book 1) by J.A. Cipriano

The Clue of the Screeching Owl by Franklin W. Dixon

The Case of the Daring Divorcee by Erle Stanley Gardner

When I Found You by Catherine Ryan Hyde

Christmas at Promise Lodge by Charlotte Hubbard

La Reina del Sur by Arturo Pérez-Reverte

Season for Temptation by Theresa Romain

Bridgetown, Issue #1: Arrival by Giovanni Iacobucci

The Dark City by Catherine Fisher