The Books of Elsewhere, Vol. 1: The Shadows (4 page)

Read The Books of Elsewhere, Vol. 1: The Shadows Online

Authors: Jacqueline West

BOOK: The Books of Elsewhere, Vol. 1: The Shadows

4.47Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Fortunately, the start of the school year was still more than two months away, and as far as making friends went, she didn’t need to worry. All the people on Linden Street looked just about as old as their houses. There weren’t even any young trees in their yards. Not counting flowers, bugs, and a few pairs of socks, Olive guessed that she was the youngest thing on the whole street.

Inside the big stone house, Olive wandered from room to room, staring at the paintings. She had tested every picture frame in the house, pushing and pulling on the paintings of dancing girls and crumbling stone castles and bowls of odd-colored fruit. All of them stuck to the walls as if they had been slathered with superglue. She had even tried to pry the painting of a romantic French couple off of the living room wall with a butter knife. All she achieved was a big gash in the wallpaper. Fortunately, Mr. and Mrs. Dunwoody didn’t notice.

She explored the upstairs bedrooms. There were five bedrooms besides the two where Olive and her parents were sleeping. “Guest rooms,” Mrs. Dunwoody called them, even though the Dunwoodys never had overnight guests. Olive imagined that all of those rooms were already occupied. Guests were living in each one of them, but had always just gone out whenever Olive went in. It made the house seem friendlier.

The first room, at the front of the house, was papered with pink roses on a pinker background. It smelled like mothballs and very old potpourri. There was a dusty wardrobe in the corner that still had a nightgown and slippers in it. There was also a great big painting of an old town somewhere in Italy or Greece, with crumbling pillars and half-formed walls, and a huge stone archway in the foreground, decorated with stern-faced soldiers three or four times the size of a human being. The other buildings showed their age, but that arch looked as solid and untouched as it must have looked when it was first carved. Olive peered down the arch’s shady tunnel. Beyond the far end, small white buildings crumbled away into the narrowing distance.

The second room was dark blue and somber, with an old hat rack and a dresser full of handkerchiefs, shoehorns, and other useless stuff. The blue room had a painting of a ballroom where an orchestra played while couples in old-fashioned evening clothes danced. Everyone looked very serious and graceful and didn’t seem to be having any fun at all.

The third room was Olive’s favorite. With its pale violet paper and tatted lace curtains, it looked delicate and grandmotherly. While the other guest rooms smelled of dust and age, this one smelled as though it had been more recently used. A very faint scent of lilacs and lilies of the valley hung in the air.

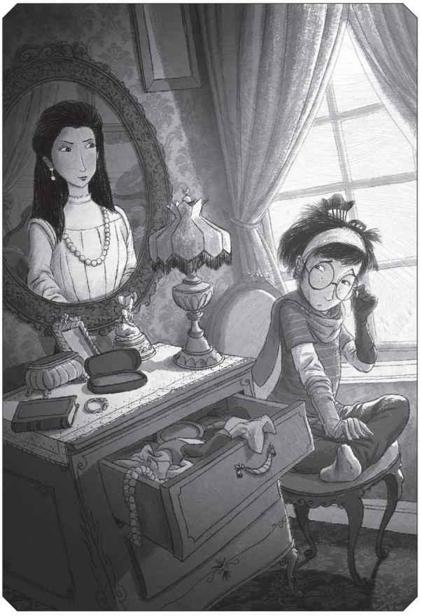

The violet room also had the chest of drawers full of old-fashioned trinkets that Olive had discovered just after moving in. Olive liked to try on the gloves and stick the tortoiseshell combs in her shortish, straightish hair. The pair of spectacles was there, too, still lying in their silk-lined case.

A portrait hung over the chest of drawers. It was of a young woman—or of a young woman’s head and shoulders, anyway—painted in soft pastel hues. The woman’s dark hair was pinned up with combs on the sides, and she wore little pearl earrings and a long string of pearl beads around her neck. The woman was pretty, Olive thought, like the actresses in the old black-and-white movies they showed Sunday afternoons on public television. Her eyes were big and dark, and she had a tiny mouth that tilted up just a bit at the corners.

One afternoon, when Olive was wearing a pink glove on the left hand, a blue glove on the right hand, three scarves around her neck, and all of the tortoiseshell combs she could find, something funny happened. Olive had taken the spectacles out of their case. They were on a long beaded chain, the kind that librarians wear. Olive put the chain around her neck and balanced the spectacles on her nose. And then the portrait

winked

at her.

winked

at her.

Olive took off the spectacles and peered up at the painting. The dark-haired woman still stared off to the left, not moving, wearing her little smile. Olive rubbed her eyes. She put the spectacles back on. The woman in the portrait winked at her again, and this time, her smile got a little wider.

Olive waited, barely breathing. Several minutes went by, but the portrait didn’t move. Olive started to think that maybe she had hit her head on the corner above the bathtub too many times. She stuffed the gloves and scarves back in the drawer and hurried out of the bedroom with the spectacles still swinging around her neck.

Once, somebody had given Olive a puzzle book with secret messages hidden in the pages. To find them, she ran a strip of red cellophane over the pictures, and the messages would “magically” appear. The messages said pointless things like, “Why did the banana leave the party? Because he had to split.” Eventually Olive had ripped up the puzzle book and used it for papiermâché. But that strip of red cellophane had given her an idea.

In the hallway, Olive stopped in front of the painting of the forest at night. She squinted down the moonlit path. As always, she got the sensation of something lurking there in the darkness—something powerful, something unfriendly. Then she put on the spectacles and slowly leaned toward the painting, moving closer and closer until her nose was almost touching the canvas.

There. She knew she had seen it before! And there it was again: a tiny white shape flitting in and out of the shadows on the path. Olive watched it run, trip on a root, and stumble. It turned, looking over its shoulder. It had a tiny, frightened face, a long white nightshirt, and a scraped knee. It got up, limping, and tried to hurry away. Olive leaned even closer, keeping her eyes on the scurrying figure. Suddenly she could feel the breeze in the dark forest rushing over her skin and through her hair. The canvas seemed to turn to jelly as her face sank through it—

Olive jerked back from the painting. She rubbed her nose. It felt clean—not at all like she had just pushed it into a bowl of Jell-O. Carefully, the way you touch an animal that might not be friendly, she stretched her fingers toward the painting. Her hand went through the frame almost as easily as if it were an open window. A tickly excitement bubbled through Olive’s body.

Tugging off the spectacles, Olive hurried down the stairs and skidded into the library. Mr. Dunwoody was working at his computer. He didn’t look up until Olive plunked down on the rug beside him.

“Dad,” Olive began, “if you wanted to try something, but you weren’t sure it would work, and you didn’t know if you should try it, what would you do?”

Her father swiveled slowly around in his desk chair. “Would it be safe to say that we’re not really talking about

me

here?”

me

here?”

“Not really.”

“Well . . .” Mr. Dunwoody leaned back in the chair. “I would say—Just a minute.” Mr. Dunwoody sat up again. “We’re not talking about anything that involves electricity, are we?”

“No.”

“Chemicals?”

“No.”

“Violence toward yourself or others?”

Olive paused. “I don’t think so.”

“All right then.” Mr. Dunwoody leaned back again, looking satisfied. “In that case, I would say: Test your hypothesis.”

“Test my hypothesis?”

“Yes. Try a dry run.” When Olive looked puzzled, Mr. Dunwoody went on. “A dry run is a testing procedure in which the potential effects of failure are deliberately mitigated.”

Olive blinked. “What?”

“It means,” said her father, more slowly, “try it in a way that won’t hurt anybody if it doesn’t work.”

“Oh.” Olive got up. “Thank you.”

“Any time,” said Mr. Dunwoody, already turning back to the computer screen.

Olive tromped back up the stairs, repeating the words “

Test your hypothesis. Test your hypothesis. Test your hypothesis

” in a marching rhythm.

Test your hypothesis. Test your hypothesis. Test your hypothesis

” in a marching rhythm.

Hershel was lying on the pillows where she had left him. Olive tucked the bear under her elbow and went to her closet, where she yanked the polka-dot laces out of her sneakers. Then she knotted the laces together and tied them snugly—but not too tight—around Hershel’s upper arm.

“All right, Hershel,” Olive whispered when they stood in front of the forest painting. Hershel was poised for takeoff in Olive’s hands, his shoelace anchor wrapped between her fingers. “Time to test the hypothesis.”

Olive tossed Hershel at the painting. He hit the canvas with a muffled thud and bounced off onto the hallway carpet.

Olive regarded him for a moment, then scooped him up. “Sorry, Hershel. I forgot about the spectacles.” She settled the spectacles on her nose and rearranged Hershel for launching. “Now beginning our second trial: in three . . . two . . . one . . . Lift-off!”

This time, Hershel flew through the frame. Olive kept a tight grip on the shoelace. She squinted into the dark forest, but she couldn’t see Hershel anywhere in the picture—he must have fallen out of sight, below the edge of the frame. The leafless trees swayed in the distance, almost like reaching hands.

Olive started to feel a bit nervous. Last year at school, the whole class had signed petitions to stop animal testing. She wasn’t sure if experimenting with Hershel counted, but it made her feel guilty either way.

To give her mind something else to do, Olive started to count to a hundred. As usual, she got lost somewhere, and one hundred came up astonishingly fast. She suspected that she had skipped not only the eighties, but the seventies and sixties as well. “Close enough,” she whispered to the empty hallway. With a step backward, she yanked the shoelace, and Hershel soared back through the frame like a fish on a hook.

Olive inspected Hershel from head to toe. He seemed calm; there were no cuts or bruises or even any dirt on him anywhere. She gave him an appreciative hug and put him back in his place on her pillows. Then she returned to the hallway, took a deep breath, and put her hands on either side of the painting.

Somewhere far down the path, she saw a tiny white shape dart and flicker. Olive leaned forward. Her face sank through the canvas, and then her shoulders, and before she could grab the frame to stop herself, her whole body toppled forward into the dark and chilly forest.

6

O

LIVE FROZE. SHE could hear the wind creaking through the bare branches. Patches of moonlight fell onto the white path at her feet. The gravel on the path poked sharply through her favorite stripy blue socks. She looked over her shoulder. Behind her, a frame floated in midair, holding a smallish painting of the upstairs hallway. Olive stuck her hand back through the frame and wiggled it around, just to make sure.

LIVE FROZE. SHE could hear the wind creaking through the bare branches. Patches of moonlight fell onto the white path at her feet. The gravel on the path poked sharply through her favorite stripy blue socks. She looked over her shoulder. Behind her, a frame floated in midair, holding a smallish painting of the upstairs hallway. Olive stuck her hand back through the frame and wiggled it around, just to make sure.

A snapping sound and the rustle of dry leaves came from the thick patch of trees ahead. Looking back once or twice at the glowing square of hallway, Olive set off along the path. At first she went cautiously, but soon her heart settled into an excited beat, like a snare drum in a marching band. Olive almost giggled out loud. It was the kind of giggle someone makes when she is playing hide-and-seek and none of the other kids can find her, even though they’ve walked past her hiding spot four times. High over Olive’s head, black branches rattled. The full moon in its oily navy sky tossed bony shadows over the path.

“Hello?” Olive called. “I know you’re here!”

There was a rustle from a cluster of shrubs some distance off the path, to the right.

“I’m not going to hurt you,” she promised, moving closer.

The shrubs gave a terrified squeak.

“You can come out,” she whispered. “Really.”

The shrubs were quiet.

Olive stepped forward and pushed apart their prickly branches. A little white figure inside gave another squeak and rolled itself up into a ball.

“Look!” said Olive. “I’m not anything to be scared of.”

“Oh,” the ball said, and began to unroll itself.

When it had unrolled completely, Olive saw that it was actually a boy with a large, round face and a very small body hidden in a white nightshirt that was several inches too long. From the top of his round head, pale hair tufted in all different directions. He looked a bit like a tiny, unthreatening scarecrow—the kind that birds end up using as a convenient perch.

“I’m Olive.”

“I’m Morton.” The scarecrow held out a small, grubby hand. Olive shook it solemnly.

Other books

Rebecca's Lost Journals, Volume 4: My Master by Jones, Lisa Renee

One Wish Away by Kelley Lynn

Lost Memories (Honky Tonk Hearts) by Thomas, Sherri

Every Waking Moment by Fabry, Chris

All The Way (The Sarah Kinsely Story - Book #1) by Berry, C.J.

The Tower of the Forgotten by Sara M. Harvey

Logan's Redemption by Cara Marsi

The Inner Circle by Kevin George

Sabra Zoo by Mischa Hiller

Staying True - A Contemporary Romance Novel by Carr, Suzie