The Books of Elsewhere, Vol. 1: The Shadows (3 page)

Read The Books of Elsewhere, Vol. 1: The Shadows Online

Authors: Jacqueline West

BOOK: The Books of Elsewhere, Vol. 1: The Shadows

7.13Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

For a long time, Olive listened. The house moaned and whispered. Wind shushed across the window. Finally, curled in a very tiny ball, with Hershel standing guard on the pillow beside her, Olive fell asleep.

3

O

LIVE WOKE UP rather late the next morning. Her father had already left for his office, but her mother was still in the kitchen, having a third or fourth cup of coffee and arguing with a science program on public television.

LIVE WOKE UP rather late the next morning. Her father had already left for his office, but her mother was still in the kitchen, having a third or fourth cup of coffee and arguing with a science program on public television.

“Good morning, sleepyhead,” Mrs. Dunwoody chirped as Olive stumbled in and pulled a stool close to the counter. “Do you want toast or cereal this morning?”

“Cereal, please,” said Olive, yawning.

Mrs. Dunwoody poured Olive’s brightly colored cereal into a bowl and set it on the countertop.

“You remember that I have to go to campus this morning, don’t you?”

Olive pretended to remember. She nodded.

“Good. It will only be for a few hours, and I know you’re old enough to take care of yourself, but if you need anything, you can call Mrs. Nivens, who lives next door. Her number is right here by the phone. The only thing you have to do all morning is move the wet laundry from the washer to the dryer. Okay?”

Olive choked on her Sugar-Puffy Kitten Bits.

“In the

basement

? I don’t want to go down there by myself!”

basement

? I don’t want to go down there by myself!”

“Olive, really. It’s just a basement. You can turn all the lights on, and you only have to be down there for a minute.”

“But Mom—”

“Olive, if you are old enough to stay home alone, you are old enough to go into the basement alone.”

Olive pouted and stirred the sludgy pink milk around in her cereal bowl.

“Good girl. Well, I’m off. Have a good morning, sweetie.”

Her mother gave her a coffee-scented kiss on the forehead and fluttered out of the house.

With her mother gone, Olive decided to get the torture over with. After opening the door as wide as it would go, she stood in the basement doorway for a moment, looking down the rickety wooden stairs into the darkness. Then, like somebody jumping into an icy cold swimming pool, she took a deep breath and raced down.

The basement of the old house was made mostly of stone, with some patches of packed dirt poking through, and other patches of crumbling cement trying to hide the dirt. The effect was like an ancient, stale birthday cake frosted by a blindfolded five-year-old.

The basement lights were just bare lightbulbs dangling on chains from the ceiling. Swags of dusty cobwebs hung everywhere: in the corners, between the lightbulbs, over the old pantry shelves built along the walls.

Olive turned on every single light before stuffing the wet laundry into the dryer. She was shoving in the last wet towel when the back of her neck started to prickle. She got this feeling whenever anyone was looking at her, and it had saved her from a lot of spitballs and snowballs. Olive whirled around. No one was there—no one she could see, anyway. Smacking the START button, she tore back toward the stairs, taking them two at a time, even though her legs weren’t quite long enough. Back in the safe sunlight of the kitchen, she slammed the basement door and took a deep breath. Then she realized that she had left all of the basement lights on.

Olive knew that wasting electricity was a terrible thing. She had learned all about it in science class. It was almost as bad as wasting water or, worse, throwing a recyclable bottle in the trash. She couldn’t leave the basement lights on all day, with the environment already in such bad shape. She would have to go back down to turn them off, and then go back up the stairs in the dark. Olive gulped.

Her parents had warned her not to let her imagination run away with her ever since she was three and had woken them night after night wailing about the sharks hiding under her bed. “Olive, honey,” her father had patiently explained, “when a shark is out of the water, it is crushed by the weight of its own body. A shark couldn’t survive under your bed.” Three-year-old Olive had nodded, and went on to imagine sharks slowly suffocating among the dust bunnies. But eleven-year-old Olive had a bit more faith in her imagination. Somehow, she felt sure that she hadn’t been alone in that basement. Someone had been watching her.

With one hand on the wall, she edged down the stairs. The stones under her fingers were rough and cold. Still, having something to touch made her feel a teeny bit safer. She stood for a moment at the bottom of the stairs and looked around. Light from the bulbs brightened a few patches of crisscrossing wooden rafters against the high ceiling. Here and there, it lit up the uneven walls, making patterns in the stone. The dryer chuffed away in the corner. Its hum echoed through the empty space.

Olive yanked the chain of the first lightbulb. Fresh shadows swooped in around her. She backed up to the second lightbulb.

Click

. More shadows flooded the room, leaving just the glow of the light over the stairs. Olive went up the steps backward this time, determined that whatever was down there in the dark couldn’t sneak up behind her. Reaching the top of the staircase, she switched off the final light. There!—something flickered in the corner. Something green and bright. Something that looked like a pair of eyes.

Click

. More shadows flooded the room, leaving just the glow of the light over the stairs. Olive went up the steps backward this time, determined that whatever was down there in the dark couldn’t sneak up behind her. Reaching the top of the staircase, she switched off the final light. There!—something flickered in the corner. Something green and bright. Something that looked like a pair of eyes.

Making a sound halfway between a squeak and a gasp, Olive skidded backward into the kitchen, slammed the basement door, and ran all the way up to her bedroom, where Hershel calmly waited on the pillows.

4

O

LIVE HAD TROUBLE getting to sleep that night.

LIVE HAD TROUBLE getting to sleep that night.

For a while, she thought she

was

sleeping, but then she opened her eyes and saw that the minute column on the digital clock had only gone up by three. Olive sighed. She punched the pillows. She kicked her legs under the bedspread so that it billowed up like a parachute. She listened to the distant sound of her parents talking between the busy clicking of computer keys.

was

sleeping, but then she opened her eyes and saw that the minute column on the digital clock had only gone up by three. Olive sighed. She punched the pillows. She kicked her legs under the bedspread so that it billowed up like a parachute. She listened to the distant sound of her parents talking between the busy clicking of computer keys.

Olive tried counting sheep, but she got lost around forty-two. Olive had never been good at counting. While learning to count to one hundred, she had always skipped the eighties completely. She had gone straight from seventy-nine to ninety while her parents had exchanged aggrieved looks above her head.

“I give up,” she said to Hershel, holding him high in the air above her. His black bead eyes caught the dim sheen of streetlights through the windows. “I’m not even going to

try

to fall asleep. I’ll just lie here, wide-awake, all night long.”

try

to fall asleep. I’ll just lie here, wide-awake, all night long.”

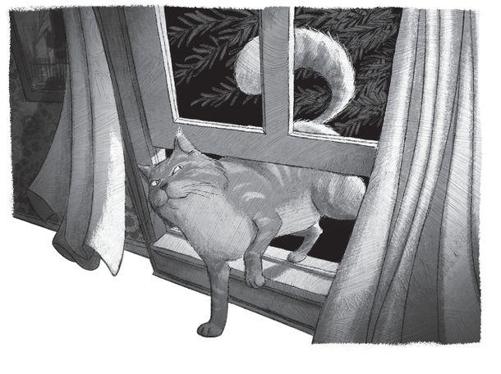

She turned on her side so she could look out of the window. There wasn’t much to see. The gauzy curtains stirred in a slight breeze, the branches of the willow tree swayed, and a gigantic orange cat pushed up the window frame and squeezed its body through.

Olive sat up. The cat stood for a moment, sniffing at the air. Then it trotted soundlessly across the room, examining the furniture with careful solemnity.

“Here, kitty, kitty,” whispered Olive.

The cat ignored her. It moved away from the dresser toward the vanity, hopping up onto the cushioned chair.

“Here, kitty, kitty, kitty,” Olive whispered more loudly.

The cat was now looking into the vanity mirror. Its reflected green eyes glanced at Olive for a split second. “That’s not my name,” it said. Then the cat looked back at its mirror image and ran one paw delicately over its nose. “Gorgeous,” it murmured.

Half of Olive’s brain said,

That cat just talked!

The other half of Olive’s brain said stubbornly,

No it didn’t.

All Olive’s mouth said was, “What?”

That cat just talked!

The other half of Olive’s brain said stubbornly,

No it didn’t.

All Olive’s mouth said was, “What?”

“I said, ‘That’s not my name,’” the cat repeated somewhat scornfully.

“But everybody calls a cat that way,” said Olive.

“What if I called you

girly

? ‘Here, girly, girly, girly.’ Rather insulting, isn’t it?”

girly

? ‘Here, girly, girly, girly.’ Rather insulting, isn’t it?”

“I’m sorry,” said Olive. “I won’t do it again.”

“Thank you.” The cat gave her a slight but gracious nod before turning its attention back to its own reflection.

“What

is

your name?” Olive asked tentatively.

is

your name?” Olive asked tentatively.

The cat stood up and stretched itself. Its orange fur puffed and settled on its back, and its tail, as thick as a baseball bat, twitched above its head. “My name is Horatio,” he said with great dignity. “And you are?”

“Olive Dunwoody. We just moved here.”

“Yes, I know.” The cat turned his wide orange face toward Olive. Then he leaped down onto the rug. Olive half expected a cat that size to make a crash like a dropped bowling ball, but he landed with surprising lightness. The cat trotted to the end of Olive’s bed and sat, looking up at her. “I suppose you plan to stay for a while.”

“Well—yes. My mom and dad said they want to stay here for good. That’s why they bought this house. We always lived in apartments before.”

“Just because they bought this house doesn’t mean that you will stay here forever.” The cat’s eyes glinted up at her like bits of green cellophane. “A house doesn’t belong to someone just because it has been paid for. Houses are much trickier than that.”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean, this house belongs to someone else. And that someone may not want you here.”

Olive felt a bit miffed. Settling Hershel in her lap, she said, “Well, I don’t care. I don’t like it here anyway. This house is creepy and weird, and it has too many corners. And . . . it’s keeping secrets.”

“You’ve noticed that, have you?” said the cat. “Very good. You’re brighter than I gave you credit for.”

“Thank you,” said Olive uncertainly.

The cat edged a bit closer to the bed. In a whisper, he said, “Keep your eyes open. Be on your guard. There is something that doesn’t want you here, and it will do its best to get rid of you.”

“Get rid of me?”

“Of all of you. As far as this house is concerned, you are intruders.” Horatio paused. “But don’t get too anxious. There’s very little you can do about it either way.”

The cat turned with a swish of his huge tail and headed toward the window. “I’ll be keeping an eye on you,” he said. “Personally, I like seeing someone new in this place.” Squishing his orange bulk through the window, the cat stepped out onto the balcony and disappeared.

Ripples of goose bumps scuttled from Olive’s toes all the way up to her scalp. She grabbed Hershel’s fuzzy body and squeezed it. “I’m dreaming, aren’t I?” she asked him. Hershel didn’t answer.

In the distance, she heard her father knocking his toothbrush on the sink. The house creaked. A twig of the ash tree tapped softly against her window, again and again, like a small, patient hand.

5

F

OR THE NEXT few days, Olive kept her eyes open.

OR THE NEXT few days, Olive kept her eyes open.

She kept them so wide open that they started to dry out. She even tried not to blink. But three days went by with nothing more unusual than Mr. Dunwoody tripping on the stairs and falling half a flight, and this was because he was reading at the time.

Horatio the cat—whether he was a dream or not—stayed out of sight. Once, Olive thought she saw him looking down at her from an upstairs window while she took a bucket of compost out to the backyard, but she really wasn’t sure. If the house was truly trying to get rid of them, it seemed to be taking its time.

Most days, Mr. and Mrs. Dunwoody stayed home, working in the library. Some days, one or both of them would go to campus to use the computers in the math lab or to work in their offices. Either way, Olive had most of the house to herself.

And Olive was used to being on her own. Each time one of her parents took a job at a different college, Olive had to switch to a new school. She had done it three times already. For weeks or months she would be “the new girl”—the one who got lost on her way to the art room, who was wearing the wrong kind of laces in her tennis shoes, who always got picked last for teams. (Of course, if Olive had been able to catch, hit, or kick a ball, this might have been different.) Like Mr. and Mrs. Dunwoody always said, she would get used to things eventually, but it was getting harder and harder. Every time she switched to a new school, Olive tried to be like a chameleon. Silently she would observe the other children and change color until she disappeared into her new environment. But she was getting a bit tired of this. If she were really a chameleon, she would have picked a nice tree and stayed there, wearing her favorite shade of green and never having to turn pink or yellow again.

Other books

Golden Paradise (Vincente 1) by Constance O'Banyon

Ice Station Zebra by Alistair MacLean

El arquitecto de Tombuctú by Manuel Pimentel Siles

Family Practice by Charlene Weir

Mitch and Amy by Beverly Cleary

The Red Tent by Anita Diamant

Dishonour by Jacqui Rose

The Poisoned Arrow by Simon Cheshire

The Amish Nanny by Mindy Starns Clark

Arcana by Jessica Leake