The Big Ratchet: How Humanity Thrives in the Face of Natural Crisis (24 page)

Read The Big Ratchet: How Humanity Thrives in the Face of Natural Crisis Online

Authors: Ruth DeFries

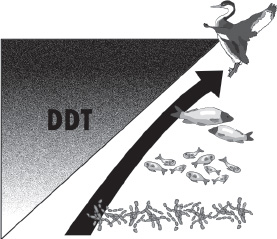

Clear Lake, California, was one of the first places to provide documented proof that the new pesticides were accumulating up the food chain. The recreation area at Clear Lake is a nesting ground for Western

Grebes, birds that feed on small fish and other aquatic life. After pesticides were applied around the lake to control gnats in 1949, the grebes began to fail to breed. Then they started to disappear. Even after the spraying stopped, the number of birds continued to fall. The concentration of DDT was 80,000 times higher in the fat of the birds than in soil and water. Bird eggshells were still thinner than normal into the 1970s, two decades after the final spray. The birds could not reproduce. Such examples of astronomical accumulation of pesticides up the food chain appeared in other places and other animals as well, among them the pheasant in the Sacramento Valley and the fish-eating pelican and the cormorant in

California’s Klamath Basin.

Prompted by a friend from Massachusetts, who complained that birds in her private sanctuary were dying from DDT sprayed by planes flying overhead, the biologist and author Rachel Carson turned her attention to gathering evidence that new synthetic pesticides were

wreaking havoc on wildlife. The result was her 1962 book

Silent Spring

. It’s impossible to overstate the influence of this book on the common person’s awareness that humanity was tampering with nature on a very

large scale.

Silent Spring

deserves the credit it gets for galvanizing an environmental movement. Carson held the chemical industry and the government accountable for the reckless use of pesticides that was exposing wildlife and people to deadly, poisonous chemicals. With a bit of hyperbole, she wrote that “for the first time in the history of the world, every human being is now subjected to contact with dangerous chemicals, from the moment of

conception until death.” She positioned the pesticide boom in the larger context of humanity’s attack on a presumed harmonious nature:

As man proceeds toward his announced goal of the conquest of nature, he has written a depressing record of destruction, directed not only against the earth he inhabits but against the life that shares it with him. The history of the recent centuries has its black passages—the slaughter of the buffalo on the western plains, the massacre of the shorebirds by the market gunners, the near-extermination of the egrets for their plumage. Now, to these and others like them, we are adding a new chapter and a new kind of havoc—the direct killing of birds, mammals, fishes, and indeed practically every form of wildlife by chemical insecticides indiscriminately

sprayed on the land.

The book became an instant sensation and remained on the bestseller lists for weeks. “The $300,000,000 pesticides industry has been highly irritated by a quiet woman author,” wrote the

New York Times

on July 22, 1962. Polarized accusations and counteraccusations followed.

Time

magazine charged the book with “oversimplifications

and downright error.” Critics branded Carson a “

bird and bunny lover.” The president of Monsanto Corporation labeled her “a fanatic defender of the cult of the

balance of nature.” With prominent articles in

The New

Yorker

and a popular prime-time television special featuring the author, Rachel Carson’s message garnered even more public attention.

US President John Kennedy set up an investigation of alleged pesticide abuses in 1962. The ensuing report vindicated Carson in a blandly worded report, concluding that “the accretion of residues in the environment can be controlled only by orderly

reductions of persistent pesticides.” Rachel Carson died of cancer in 1964 at the age of fifty-six, before she could see the full outcome from

Silent Spring

.

Newly organized environmental activists went to court to push for a ban on DDT, citing evidence of declining osprey populations

on Long Island, New York. In 1969, when the chemical showed up in Lake Michigan’s Coho salmon, the state of Michigan banned the use of the pesticide. The newspaper ran an obituary: “Died: DDT, age 95, a persistent pesticide and onetime humanitarian. Considered to be one of World War II’s greatest heroes, DDT saw its reputation fade after it was charged with murder by author Rachel Carson. Death came on June 2 in

Michigan after a lingering illness.” Sweden and Norway were among the first countries to ban DDT, outlawing it in 1970. The United States banned the chemical nationwide in 1972 with exceptions for public health emergencies. Many industrialized countries followed suit.

Heated arguments among scientists, government officials, and representatives of the chemical industry exposed the complexities surrounding the use of dangerous chemicals as a way to manipulate nature. Despite the thinly veiled vested interests of the chemical industry to sell their products, the issue was—and still is—not completely black and white. Yes, the pesticide bonanza led to excessively high doses of chemicals. More benign ways to control pests were suddenly ignored, and the new methods endangered both people and wildlife. But judicious use of the chemical does have its place. It fights back against the tragic human toll levied by malaria, particularly in the tropics. Pesticides were also contributing to increasing yields that made food more affordable.

Norman Borlaug, a key scientific figure, whose life’s work was to spread the benefits of technology to improve food production in the developing world, clamored back with humanitarian arguments. He assailed the ban as “unwise legislation that is now being promoted by a powerful group of hysterical lobbyists who are provoking fear by predicting doom for the world through chemical poisoning,” and he warned that with the ban “the world will be doomed not by chemical poisoning but from starvation.” The true goal, in his mind, was “to increase agricultural productivity to feed the growing number of

people on our planet.”

Exposure to the chemical declined after the ban, but DDT’s story was far from over. In the 1970s, scientists started to report that the persistent chemicals could travel long distances from the fields and forests where people had sprayed them. DDT was lofting into the atmosphere as vapor or attached to particles. It was showing up in the open ocean, on the deserts, and in the Arctic. Magnification in the food chain meant that Arctic fish, seals, and whales, as well as the indigenous peoples who hunted and ate these animals, were being exposed to

high concentrations of the chemical. DDT in Inuit mothers’ breast milk was among the highest in the world—despite the fact that no DDT had ever been

sprayed so far to the north.

The long-range transport of DDT and gathering evidence of possible links with cancer meant that DDT sprayed in one country could affect people’s health in a country far away. The issue moved from a national concern to a global one. More than ninety countries consented to the Stockholm Convention in 2000, agreeing to control the production and use of the “dirty dozen” chemicals labeled as persistent organic pollutants, or POPs for short. POPs are chemicals that remain in the environment for a long time, disburse widely over long distances, accumulate in the fatty tissue of living organisms, and are toxic to humans and wildlife. The dirty dozen includes DDT and similar pesticides that control pests in agricultural fields, lawns, gardens, and homes, as well

as industrial chemicals and flame retardants. The convention entered into force

on May 17, 2004. Some countries, notably the United States, have yet to ratify the convention as of this writing.

The Stockholm Convention left tropical countries, where malaria gnaws at the health and productivity of its citizens, with a dilemma. Ban DDT to reduce the possibility of long-term health effects, but forgo DDT for controlling disease-carrying mosquitoes. Or spray DDT to control the mosquitoes, and risk the long-term health effects from DDT. Many developing countries understandably chose the latter. They requested, and were granted, exemption for use of DDT to control malaria. Today, houses in many countries in Asia and Africa are sprayed to control mosquitoes, though resistance to the pesticide hampers efforts to lessen the scourge of the disease.

Scientists do not yet completely understand the precise long-term effects of DDT and similar pesticides on human health, though prudence suggests that high doses of such a toxic chemical pose danger. A growing body of evidence concludes that cancer, hormonal imbalance, diabetes, birth defects, and developmental abnormalities may occur where people come into contact with high amounts of the synthetic chemicals through the food they eat or the air they breathe. Uncertainties surround the human health effects of the many thousands of synthesized chemicals that exist in the environment, many of which aim

to control agricultural pests.

There’s one clear lesson from humanity’s long battle with insects and vermin to keep them from eating into fields and gardens: there is no magic bullet to ward off pests. Even the most toxic chemicals sprayed from the sky can only temporarily rid the fields of pests before resistant ones take over. Except for the accidentally eradicated Rocky Mountain

locust, pests of all stripes and colors—weeds, insects, rodents, bacteria, fungi, and all kinds of critters that munch on crops—are here to stay.

Once the widespread availability of synthetic pesticides became part of humanity’s toolbox, there was no going back to the days with few defenses against malaria-carrying mosquitoes, crop-ravaging locusts, and blights like those that destroyed the Irish potatoes and American corn. The DDT bonanza was winding down in the 1970s, but the need to keep pests from eating the garden was as strong as ever. The search was on for more benign solutions that did not involve toxic chemicals that persisted for long times, traveled around the world to unsuspecting places, and accumulated in human breast milk. The bonanza years for DDT proved to be a dark time for entomologists like William Hoskins who sought better ways to control pests and questioned the indiscriminant use of toxic chemicals. With DDT’s fall from grace and the reality that even poisonous chemicals could not keep pests at bay, scientists again could turn their attention to learning from traditional practices, practices in cultures around the world that built on humanity’s long experience with pests.

Hoskins’s investigations of “nature’s own balance” came back on the agenda, with the central tenet that humanity can only hope to manage rather than control pests. President Richard Nixon gave a nod to the reinvigorated science in a 1972 message to Congress, stating that “new technologies of integrated pest management must be developed so that agricultural and forest productivity can be maintained together with, rather than at the expense of, environmental quality.” And “integrated pest management,” Nixon said, “means judicious use of selective chemical pesticides in combination with

nonchemical agents and methods.” Strategies to employ natural predators of pests, mixed crops rather than monocultures, and locally successful strategies, such as those of the Guatemalan and African farmers, are all part of this approach.

Integrated pest management is far from the dominant mode for farms in the industrialized world, but the approach has made it back from the sidelines since the DDT

bonanza went bust. The South American cassava mealybug that created such devastation in Africa, for example, came under control with the introduction of a tiny wasp that preys on

the unwelcome bug. Screwworm flies that lay eggs in animal wounds no longer trouble cattle producers in the southeastern United States following a program to release millions of radiated, sterilized males so that the females would not

produce viable offspring.

The chemical industry has responded to the demand for alternative chemicals with less damaging characteristics than DDT. Pesticides such as pyrethrins, derived from chrysanthemum flowers, break down in sunlight and do not persist in the environment. New pesticides aim their toxicity at specific pests, unlike DDT, which does not discriminate among its targets. Miticides, to control mites, rodenticides for rodents, and molluscicides for snails and slugs, as well as other pesticides named for their specific targets, aim to disrupt pest life cycles without affecting other organisms. Some of the research behind the development of these more benign pesticides took place at the same Rothamsted Experimental Station where Lawes and Gilbert experimented with chemical fertilizers more than a century earlier. The list of chemicals brought to market numbers in the many thousands. The perpetual race with resistance means that companies must continually add new chemicals to the list.

During the DDT bonanza, people dusted DDT directly on their bodies, airplanes sprayed it from overhead, and farmers spread more than was needed on their fields. Children rode their bicycles behind trucks fumigating neighborhoods. Safety precautions were not heeded, and accidental deaths and poisonings were not unusual. Today in the developing world there are still millions of reported chemical poisonings and hundreds of thousands of pesticide-related deaths each year from

unsafe handling practices. Part of the pivot away from the dangers of pesticides surely lies in preventing such needless tragedies.