The Big Ratchet: How Humanity Thrives in the Face of Natural Crisis (21 page)

Read The Big Ratchet: How Humanity Thrives in the Face of Natural Crisis Online

Authors: Ruth DeFries

At the end of the nineteenth century, the US Department of Agriculture had formalized the acquisition of plant specimens through an Office of Foreign Seed and Plant Introductions. A few decades later, two scientists on the staff, Howard Morse and Bill Dorset, packed up their families and took off on a soybean-collecting odyssey. Between 1929 and 1931, they traveled throughout China, Japan, and Korea. From fruit and vegetable markets, food and flower shops, botanical gardens, farms, factories that made food from soy, and the wild, they brought back more than 10,000 specimens of soybeans. Some were large and some were small; some were red, others black, yellow, or striped; some were round, and others were oval. Here were the genetic ingredients that soybean breeders needed, just as the freak corn from county fairs had provided the seed men with the genetic variety they needed to produce new, robust varieties of high-yielding corn. Breeders

could select for higher yields, different climates, and

shorter plants that stayed upright.

In 1922, entrepreneur Augustus Staley, of Decatur, Illinois, had seen the commercial potential in the crop. He paid Illinois farmers to grow soybeans and built the first factory to process the harvest. The profitable products turned out not to be soy sauce, tempeh, and tofu, but oil crushed from the bean, and soymeal to feed cows, chickens, and pigs. The crop made the company’s fortune and over time made Decatur the soybean capital of the world. Plant breeders used the soybean seed bank to create varieties palatable to animals that yielded more oil. The soybeans were not planted on fields as forage for cattle; rather, the route to a cow’s stomach wound circuitously through the soymeal-producing factories and on trucks and rails back to the farms. After World War II, the shift from soy as a food to commercial production of soybean oils for margarine and shortening, and as feed for livestock destined for meat or milked for dairy products, became complete. The United States took its place as the world’s top soy producer, a place rivaled by Brazil, home to

Mato Grosso’s Soybean King, in more recent times.

The early twentieth-century genetic twists joined chemical fertilizer and fossil-fuel-powered machinery to pave the way for ratcheting yields of industrially produced corn, wheat, and soy across the Midwest. Scientists in publicly funded universities did much of the theorizing and hard work to coax out higher yields by breeding new varieties. With prospects of patents and profits, private companies also

started to take on the role.

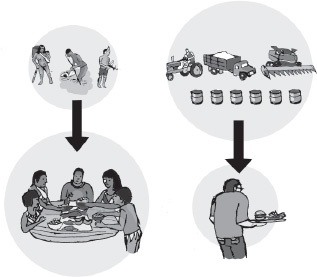

The prairies and flat expanses of fertile soil went on to become one of the world’s main centers for industrial agriculture. When the century started, almost every farm in the country was multifunctional,

growing vegetables, harvesting fruit trees, and raising chickens, horses, dairy cows, and pigs, all at the same time. As the century progressed, small farms amalgamated into larger ventures. The large farms became more specialized, growing only a handful of crops, most often including corn, wheat, or soy. And as new machinery arrived to do the jobs of the laborers, only a small fraction of the population

remained to work the large farms. Most of the rural population moved to the cities. Contrary to Crookes’s late nineteenth-century prediction that the United States was “soon to enter the list of

wheat-importing countries,” the heartland began to produce an abundance of food to feed the growing cities of America and to export around the world.

Crookes’s prediction proved so wrong in part because he did not foresee the enormous gains to be made from breeding plants. Nor did he anticipate the subsidy to animal power that fossil fuels could provide. In Midwestern monocultures, the energy to produce and transport food comes from the ancient sun, in the form of fossil fuels, with only a small amount of human labor to run the machines and drive the trucks. In 1900, before tractors came onto the scene, more than 20 million horses and mules were supplying energy to the farms of the United States. Five decades later, more than 3 million tractors, and fewer than 8 million horses and mules, were

doing the work on US farms. The calculus had changed completely from humanity’s foraging days. Hunting and gathering societies need to have a positive return on their energy investment, but fossil fuels make possible a negative return. When reduced to common units of calories, the amount of energy gained can be far less than the amount expended, so long as the cost of fuel is within reason. Accounting for the full chain of farming, transporting, processing, and packaging, and then for household storage and preparation, the energy costs today in terms of the calories needed to produce all the fruits, vegetables, eggs, milk, meat, and other products in the US food system amount to seven to fifteen times more than the payback in

calories consumed. In other words, every calorie on the dinner plate uses up seven to fifteen times more energy, in common units of calories, to produce and transport than it

provides to the person who eats it.

As one would expect, the Midwest’s pivot from many small, diverse farms to fewer large, fossil-fuel-based monocultures permeated into the diets of Americans and around the world. The impacts of the Big Ratchet were starting to be seen in pantries and on kitchen tables.

There is rarely a universal pattern that applies to all countries and all cultures. The American geographer Merrill Bennett came as close to finding one as any. He observed in the early 1930s—before the Big Ratchet was even in full swing—that human societies shared a nearly ubiquitous trait. Despite differences in cuisines, religious taboos, and preferences, when people get wealthier, they eat fewer starchy foods—that is, they eat less wheat, corn, rice, and potatoes and more meat,

poultry, eggs, milk, and cheese. “The national ratios of cereal-potato calories to total food calories . . . provide a rough indicator of relative per capita levels of national income, or of relative consumption levels, planes of living, or economic productivity so far as these may correspond one with the other,” he concluded, having analyzed what people ate

in 1935 in countries around the world. Only about one-tenth of the world’s population at the time, most of them in the United States, ate diets with more than six out of every ten calories coming from meat and non-starchy foods. More than two-thirds of the world, mostly in populous Asia and less densely populated Africa, subsisted on diets with two out of ten calories

from non-starchy foods. Only small pieces of meat and eggs once in a while were the routine. Meal after meal dominated by rice or some other starchy staple was more often the norm.

Ethical issues about eating animals aside, meat and other animal products are prized foods in many cultures. Animals convert the sun’s energy embedded in the food they eat into nitrogen-containing, essential protein. The downside is that the protein bears the energy cost that cascades up the food chain from the animals’ maintenance charges.

Some animals are more costly in energy terms than others. Beef cattle are the costliest. A pound of edible meat from cattle raised for meat takes nearly thirty-two pounds of feed. That means beef cattle convert only 5 percent of the protein they eat into protein that ends up on the plate. If the cattle feed is soy or corn—as is the destiny of most of those crops produced in the United States—the energy to produce the lost calories has likely come from the sun’s ancient energy in fossil fuels. If the cattle graze on grass that humans would not be able to digest, then eating the meat exploits the sun’s energy to get protein without the energy subsidy from fossil fuels. Chickens, whether for meat or for eggs, along with dairy-producing cows, convert feed into protein more efficiently than cattle raised for meat. For chickens raised for their meat, 25 percent of the protein in the grain they eat ends up on the plate. For

chickens raised for their eggs, the figure is 30 percent, and the figure is 40 percent for dairy cows. Differences in animals’ diets and efficiencies in converting protein make arguments about the pros and cons of meat diets more nuanced than simplistic

assertions may imply.

Bennett concluded that people worldwide switch to less starchy diets when they can afford to. That was before the spread of fossil fuels to power machines and drills to pump water for irrigation, the pesticide bonanza, high-yielding seeds for wheat and rice, and chemical fertilizers. The ratcheting food production from all these twists of nature in the latter half of the twentieth century put Bennett’s law to the test. In many places around the world, diets have changed dramatically, both to our benefit and our detriment, as we’ll see later on.

As monocultures marched across the Midwest, and the Big Ratchet started to take off in the early decades of the twentieth century, the world’s population surpassed 1.5 billion. By midcentury, the number

climbed almost another billion. New York took the title from London as the world’s largest city, and the proportion of people living in cities more than doubled, to about three out of ten. This upswing was still modest compared to the meteoric rise in store for the second half of the century.

The monocultures that transformed the American Midwest ratcheted up yields dramatically, but they also amplified another problem: other species besides ours could join in the feast. Pests pilfering the proceeds of human ingenuity were another conundrum of settled life, one of our own creation, and one demanding more twists of nature to solve. Now the problem was how to get rid of unwelcome foragers. Again, a solution had created a problem that cried out for yet another solution.

T

HE SKY DARKENS

. A rumbling from overhead crescendoes to a roar as a brownish cloud descends on a helpless farmer’s field. A million-strong swarm of locusts devours the entire crop in a matter of hours. When the locust swarm rises back up to the sky, like a wave of moving water, it leaves devastation in its wake. The swarm moves on to find its next meal, and then the next. By the time the locusts’ migration season comes to an end, the pests will have eaten through leaves and stems and reduced green fields to lifeless barren.

Such disastrous scenes occur across hundreds of thousands of acres in West Africa roughly every ten to fifteen years, when massive numbers of locust hatchlings emerge from the soil during a dry spell that follows heavy rainfall. Once the hungry insects take flight, they devour the equivalent of their body weight each day from whatever food they encounter, including the West Africans’ staple crops of corn, millet, and rice.

The locusts had a banner year in 2005, when they spread from West Africa across the northern part of the continent and then headed

toward Portugal. Eastern Australia also suffered a record-breaking plague of the insects that year. Although 2005 was notably devastating, it was not the only time the world’s worst agricultural pest had laid waste to farmers’ lands. Such plagues predate even biblical times, with the ravenous appetites of locusts leaving behind trails of distraught farmers and

food shortages throughout history.

Today, North America is the only inhabited continent free from the horrific damage of locust plagues. It was not always so. As settlers moved westward in the late 1800s, transforming prairies to fields, a swarm of hungry Rocky Mountain locusts could ruin a corn or wheat field without warning. This is what happened to the Minnesotan family depicted by Laura Ingalls Wilder in

On the Banks of Plum Creek

, the children’s book in the beloved Little House on the Prairie series. A glittering cloud of millions of locusts descended, just before the harvest, on the wheat field that the family had struggled to nurture. With the crop ruined, Pa had no choice but to travel east to find work in the city and leave the rest of the family behind.

Book lovers disagree on whether the Little House books are fiction or nonfiction, but one thing is certain: dark clouds of Rocky Mountain locusts moving eastward were not fiction in 1873. They ruined crops in newly settled farms throughout Nebraska, Iowa, Minnesota, and the Dakotas. Swarms devastated crops from Texas to North Dakota in 1875. Farmers tried to ward off the locusts with smoke from fires, and they used tar-coated traps to capture the locust hatchlings. Nothing deterred the pests. They even ate through blankets that the pioneers spread over their gardens with hopes of saving their vegetables.