The Big Ratchet: How Humanity Thrives in the Face of Natural Crisis (28 page)

Read The Big Ratchet: How Humanity Thrives in the Face of Natural Crisis Online

Authors: Ruth DeFries

Today’s ready availability of ice cream—along with a host of other sources of fat and sugar—is part of the double-edged nature of the Big Ratchet. A similar shift happened when our ancestors made the fateful transition from forager to farmer, when they gained a surplus supply not of fat and sugar, but of storable grains. And their diets took a blow then, too. Although it’s impossible to know exactly what our foraging ancestors ate, teeth and skeletal remains make it clear that the first settlers ate more starchy foods, less wild meat, and fewer fruits, seeds, and plants than their forebears.

As American geographer Merrill Bennett observed in the 1930s, throughout history people ate more or less animal products—meat, dairy, and eggs—according to their wealth. As the Big Ratchet has unfolded, the amount of wealth required to eat large quantities of these products has dropped precipitously. The Big Ratchet’s abundance of soy and corn, for the first time in history, could compensate on a grand scale for the enormous loss of energy inherent in raising cows, pigs, and chickens for meat. Cheap grain to feed livestock made meat a more affordable option.

No country proves Bennett’s Law better than China. A survey of more than 5,000 people in the late 1980s showed that the amount of rice and wheat in their diets declined and the amount of fruits and vegetables rose in just over a decade. In the same time period, the amount of eggs and poultry in the diets of these Chinese subjects nearly doubled. They were eating more pork and fish, too. Overall, as the Chinese economy surged forward, the typical diet became fattier, meatier, and

less starchy. The number of hungry people declined, but the number of overweight people shot up. The transition was faster for urban-dwelling

Chinese than for those in the countryside. The same sequence is playing out in countries throughout the world. In the industrialized world, the transition to more animal-based and less starchy diets occurred earlier and more slowly than for today’s populations, as the ratchets were turning at a less fervent pace. In many countries where economies have taken off more recently—Brazil and China being two prominent examples—the transformation of diets

has come fast and furious.

Bennett was right about the switch from starchy to high-fat, animal-based diets, a shift that might seem to recover some of what was lost when farmers’ starchy diets took over from our

foraging ancestors’ fare. But Bennett could not foresee another development that further complicated the story in more recent times: the source of the fat. When he made his observations in the 1930s, the fats that crept into the diet were from milk, butter, lard, tallow, and marbled red meat. As the Big Ratchet came into full swing after the century’s midpoint, another way to get fats made them even more available. Motorized machines to press the seeds of cotton, soy, corn, and mustard-like rape plants could extract oil cheaply. Petroleum-based chemicals could dissolve the oil out of the seeds remaining in

squashed, solid cakes. Suddenly, people could cook, bake, and fry with inexpensive vegetable oils from crushed seeds and plants.

Then another technology ramped up the path to more fat-laden, high-calorie diets. Factories could transform liquid vegetable oils into margarine and vegetable shortenings. The new forms were solid at room temperature, so they lasted longer and needed no refrigeration. The similarity to animal fats appealed to cooks. In the United States, the trade name was Crisco. In India, Dalda was the brand name for the new marvel. Underlying these marvels was a process to add hydrogen to liquid oils. It earned its inventor, the French chemist Paul Sabatier, a 1912

Nobel Prize. His procedure made solidified vegetable oils a cheap alternative

to butter and lard. It was many decades before the unhealthy downside of the pivotal invention came to the fore.

Thanks to the Big Ratchet, access to oils rapidly increased. Oil from soybeans grown in the United States and South America; palm oil, mainly from Southeast Asia; and sunflower, safflower, and cottonseed oils were no longer limited to the well-off. A United Nations report on the diets of people in eighty-five countries in Europe, the Americas, Asia, and Oceania revealed in 1969 that industrially prepared vegetable oils, rather than oil from nuts and locally crushed oilseeds, were leading people to fry instead of boil their food. They also found a sharp increase in the amount of sugar and sugar-sweetened food in diets around the world as people began to be able to afford to

sweeten their diets. Further changes came with another inexpensive source of sugars in the early 1970s, when Japanese scientists filed a patent claiming “a novel process for the production of sweet syrups” to separate sugar from

starch on an industrial scale. High-fructose corn syrup, produced in factories from corn instead of sugarcane or sugar beets, became the main sweetener in the United States for industrially produced foods, from yogurts to cereals to sugary drinks. Among its consequences: Americans, on average, consumed 222 more calories each day from beverages in 2002 than in 1965,

mostly from sugary drinks.

Inexpensive sources for high-calorie vegetable oils and sugar leveled the playing field for people to partake in diets loaded with fat and high in calories. As the Big Ratchet progressed, the human propensity for eating fats and sugars drove this new diet to every rung of the economic ladder in rich countries and well into the

populations of poorer ones. The climb up the ladder was

steepest in cities. The numbers of overweight people soared, even in places where too little might be the more common expectation—in Brazil it increased from twenty-four out of every hundred women in 1975 to thirty-eight in a hundred by 2003;

in Bangladesh from three out of a hundred in 1996 to twelve in a hundred by 2007; and in Kenya from fifteen out of a hundred in 1993 to

twenty-six in a hundred in 2003. Even the diets of Inuits have changed under the Big Ratchet, with white bread, sugar, margarine, and hamburgers encroaching on ancient dietary traditions of

moose, caribou, and a variety of plants.

From the perspective of those who work to reduce the world’s heart-wrenching poverty, there is some good news in the massive dietary shift. There’s no point romanticizing the diet of the poor rural farmer whose back-breaking labor can scarcely feed a family. Their diets are monotonous and lack the diversity of nutrients that keep people healthy. Day after day of coarse grains and starchy roots like cassava is the norm. Fruits and vegetables are a rarity, not to mention milk or meat. To the extent that the Big Ratchet allows a more varied and nutritious diet, and that purchased food secures against lean times from droughts or floods, the news indeed is good. But the shift can throw out the baby with the bathwater. White bread, refined white rice, and processed foods often replace more nutritious, traditional whole grains. The irony is that while the elite in the industrialized world (myself included) pay top dollar for whole grains like quinoa and amaranth, those beginning their climb up the nutritional transition are turning away from

traditional, healthy options.

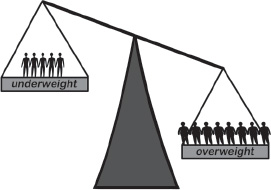

The nearly worldwide epidemic of obesity and the loss of traditional nutritious foods fit prominently in the bad news ledger of the Big Ratchet. Today, fewer than a billion people are going hungry day after day, but

more than a billion are overweight. The numbers of the hungry are falling while the numbers of the overweight are climbing. For every five people who were suffering from chronic hunger at the end of the 2000s,

eight people were overweight. The combination of easily available, inexpensive, calorie-dense foods and the sedentary lifestyles of urban living have put a major blemish on the Big Ratchet. Snack

foods, sugary drinks, and processed foods that line the aisles of grocery stores and blast from menu boards of fast-food joints are as much a consequence of the Big Ratchet as

tractors, fertilizers, and pesticides. In the United States, projections into the future estimate that over half of adults in the United States could be obese and more than 86 percent

overweight by the year 2030. Cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and a host of other afflictions associated with obesity threaten to turn the Big Ratchet’s successes into failures unless a pivot to more healthful diets occurs. Indeed, the hatchet is already falling, and not only on the wealthy parts of the world. Girths are getting wider throughout the developing world, and people are suffering from diseases related to being overweight as much as they are from

diseases related to being underweight.

The Planetary Machinery Lashes Back

The impact on the human diet as we transform from farmer to urbanite is likely as profound as the one our species experienced in the transition from forager to farmer. But the impact stretches far beyond waistlines

and human health. The growing consumption of meats and oils around the world makes environmentalists shake their heads in

dismay, and for good reason. At one point, exploding population growth seemed like the monster that might finally prove that the planet’s support system cannot endlessly supply more without striking back. While it is true that the bulge in our numbers will add several billion more mouths to feed by midcentury, the end of the great demographic upheaval is in sight. As smaller families wind down the acceleration of the twentieth century, the numbers will stabilize, and the specter of more growth will recede. But another equally demanding wave is sweeping across the world. The Big Ratchet’s massive increase in production has enabled aspirations for more food, and more animal-based diets, to become a reality. The consequences of the combination of more people with greater dietary aspirations strike at the heart of the three fundamental requirements needed for a habitable planet: a stable climate, a planetary recycling apparatus, and a smorgasbord of life.

As greenhouse gases in the atmosphere climb, the chances of meeting the first requirement recede. Agriculture poses a direct risk to the climate. The sources of greenhouse gases from agriculture are many. They include nitrous oxide from fertilizer and manure; methane from the double stomachs of cows and goats and from inundated rice paddies; and carbon dioxide from the fires where people clear forests to grow food. These sources together—not even including the fossil fuels that power the Big Ratchet—contribute more than a quarter of all humanity’s

contributions to greenhouse gases. Cows are the worst offender. Many times more greenhouse gases are released in the course of producing a pound of beef than are released in producing the same amount of chicken, and even more compared to

producing a pound of potatoes.

Whether changes in climate from humanity’s meddling with the greenhouse effect are truly catastrophic for our species remains to be seen. Nevertheless, the expectation of the stable Holocene climate—the

climate that has prevailed since humans transitioned to farmers—is no longer valid. Certainly, farmers’ expectations for the best time to plant seeds and which crops to grow are turning topsy-turvy as the amount of greenhouse gases

in the atmosphere climbs. With more people with higher aspirations, the need to produce enough food without increasing the burden of more greenhouse gases is clear.

The planet’s recycling machinery that keeps plants nourished and watered was the second requirement in our search for a habitable planet. Here, too, the twists of nature to produce more and more food interfere. Fritz Haber’s process transforms nitrogen in the air into plant-nourishing forms, but no one has yet invented an opposite process to return excess fixed nitrogen to the air. Instead, it runs into streams to create havoc in lakes and coastal waters. Modern sewage systems break the cycle of phosphorus from field to food and back to the field. The meddling with water’s journey from clouds to rivers to oceans through massive withdrawals of fossil stores beneath the ground and diversions from rivers calls into question whether water will be

sufficient for the coming demand. The Big Ratchet has made humans a major player in the planet’s recycling apparatus. We are still learning how to play our new role.

The most important requirement in our search for a habitable planet, the smorgasbord of life that evolved over millions of years, is perhaps the one that the Big Ratchet threatens most clearly. The march of the plow has already replaced the world’s prairies, savannas, and many of the forests of Europe and North America with

fields and pastures to grow food. With each tree that falls and every prairie plowed under, more plants and animals lose their homes. The bison’s slaughter and the near extinction of the Asiatic lion are among the most visible casualties of a planet usurped to feed a single species. With the lush rainforests of South America, Southeast Asia, and Central Africa the only viable places left for the plows and chainsaws to clear, the prospects for thousands, perhaps millions, of species look grim.

The Big Ratchet reached full force in the 1980s, with the infamous “hamburger connection” linking Central American forests, decimated to graze cattle, to beef that wound up in

fast-food chains in the United States. Indeed, the double blow of more people aspiring to richer diets links far-flung places around the world in many ways. There’s the “palm oil connection,” linking the disappearing forests of Southeast Asia with India and China, and the “soy connection,” linking the Amazon forests with Europe and Asia through feed for

chicken, pigs, and cattle. The intertwining and growing connections spell bad news for the species living in these forests.