The Beasts that Hide from Man (33 page)

Read The Beasts that Hide from Man Online

Authors: Karl P.N. Shuker

At that same meeting, a Dr. John Barclay, who had examined some of the beast’s remains in Orkney, presented a paper in which he described the vertebrae, skull, and one of the creature’s legs. His paper, accompanied with detailed diagrams, was published in 1811, within the society’s memoirs, and attracted a great deal of attention.

The vertebrae were very striking, resembling cotton reels, and were cartilaginous, but with calcification that radiated from the center of each vertebra in a star-like pattern. The leg was also cartilaginous, but was not a real, jointed leg at all; it was merely a fin.

To many people, these features meant little, but they meant a great deal to the eminent naturalist Sir Everard Home, who was working at that time upon an exhaustive study of the basking shark

Cetorhinus maximus

, the world’s second-largest species of shark, but generally harmless, living on plankton. When Home heard about the Stronsay beast, he felt sure that it must have been a shark. This is because the only creatures to have cartilaginous vertebrae are sharks and rays, and the only creatures to have cartilaginous vertebrae with star-shaped calcification are sharks. Furthermore, when he compared the Stronsay beast’s vertebrae and other salvaged remains with the corresponding portions of a known specimen of basking shark, they matched very closely.

But the long-necked, six-legged, mane-bearing Stronsay beast

looked

nothing like a basking shark—so how could this drastic difference in appearance be resolved? In fact, it was quite simple. When basking shark carcasses begin to decompose, the entire gill apparatus falls away, taking with it the shark’s characteristic jaws, and leaving behind only its small cranium and its exposed backbone, which have the appearance of a small head and a long neck. The triangular dorsal fin also rots away, sometimes leaving behind the rays, which can look a little like a mane—especially when the fish’s skin also decays, allowing the underlying muscle fibres and connective tissue to break up into hair-like growth. Additionally, the end of the backbone only runs into the top fluke of the tail, which means that during decomposition the lower tail fluke falls off, leaving behind what looks like a long slender tail. The pectoral and sometimes the pelvic fins remain attached, but become distorted, so that they can (with a little imagination!) look like legs with feet and toes, and male sharks have a pair of leg-like copulatory organs called claspers, which would yield a third pair of legs. Suddenly, the basking shark has become a hairy six-legged sea serpent.

Over the years, almost all of the Stronsay beast’s preserved remains have been lost or destroyed, but three vertebrae are retained in the Royal Museum of Scotland, the last remnants of the world-famous Stronsay sea serpent. Its mystery, conversely, continues to the present day, and for very good reason. The longest

conclusively

identified basking shark that has been accurately measured was a truly exceptional specimen caught in 1851 in Canada’s Bay of Fundy; whereas the average length for its species is under 26 feet, this veritable monster was a mighty 40 feet, three inches. Yet even that is almost 15 feet less than the Stronsay beast. Even the largest scientifically measured specimen of the world’s biggest fish—the whale shark

Rhincodon typus

—was only(!) 41.5 feet long. So was the 55-foot Stronsay beast really a basking shark, or could it have belonged to a still-unknown, giant relative?

Bearing in mind that one of the world’s largest known sharks, the formidable megamouth

Megachasma pelagios

, remained wholly unknown to mankind until November 15, 1976, when the first recorded specimen was accidentally hauled up from the sea near the Hawaiian island of Oahu, the prospect of undiscovered species of giant sharks still eluding scientific discovery is far from being as unlikely as one might otherwise assume.

In December 1941, history repeated itself in the Orkneys when a strange carcass, 25 feet long, was washed ashore at Scapa Flow. Its superficially prehistoric appearance was presumably sufficient for Provost J.G. Marwick, who had documented it in detail in a local newspaper account

(Orkney Blast

, January 30,1942), to dub this enigma “Scapasaurus.” Fortunately, a single vertebra from its remains was preserved and retained at the British Museum (Natural History), which identified it as a basking shark.

ZUIYO MARU

On April 25,1977, the decomposing carcass of a huge, plesiosaur-like beast was caught in the nets of the Japanese fishing vessel

Zuiyo Maru

, trawling in waters about 30 miles east of Christchurch, New Zealand. The carcass, about one month dead, measured roughly 33 feet long, was in an extremely advanced state of decomposition, and smelled so awful that the crew very speedily cast it overboard, but fortunately not before its measurements were recorded, a few fibres were taken from its carcass, and some photos were obtained of it.

Biologists were very perplexed by the photos, and all manner of identities were offered, ranging from a giant sea lion, or a huge marine turtle, to the popular plesiosaur identity, or a whale. For quite a time, its true identity remained undisclosed, until the fibres from it were meticulously analyzed by Tokyo University biochemist Dr. Shigeru Kimora. During his research, he discovered that the samples contained a very special type of protein, known as elastoidin, which is only found in sharks and rays. Once again, the scientific world had been fooled by a deceptively shaped decomposing shark carcass—equally, however, it was a carcass of remarkable length. Just

another

exceptional basking shark?

On April 14,1998, two beachcombing boys, Peter Jennings and Neil Savage, discovered a strange, unidentified, decomposing carcass washed ashore at Greatstone in Kent, England. Measuring about eight feet long, it still possessed a skull, a series of large vertebrae, and some rotting body tissue. Intriguingly, however, the skull was said to bear a pair of short curved horns! Tragically, council workmen disposed of the carcass before tissue or skeletal samples could be taken from it and examined, but some good photographs were obtained. Not long afterwards, Fortean writer Paul Harris contacted me concerning this putative sea serpent, kindly supplying me with a couple of newspaper cuttings

(Kentish Express

, April 19,1998;

Folkestone Herald

, April 23, 1998) that contained photos of its remains, plus various additional details that he had gathered during his own investigation of this case.

As soon as I saw the photos, I realized that the carcass was strikingly similar to the famous Hendaye sea serpent corpse of 1951, which had been conclusively identified by cryptozoologist Dr. Bernard Heuvelmans in his classic tome

In the Wake of the Sea-Serpents

(1968) as that of a basking shark. All of the telltale features were present—the cottonreel-shaped vertebrae, the long triangular snout, and, most distinctive of all, a pair of slender curling “horns” or “antennae” projecting from the snout’s base. These are in fact the rostral cartilages that, in life, raise up the shark’s snout. However, one can readily appreciate that to eyewitnesses not acquainted with shark anatomy (particularly

decomposing

shark anatomy!), the presence of “horns” might well be enough to make them assume that a strange-looking carcass like this one must surely be something more exotic than a rotting basking shark.

Another potentially promising sea serpent corpse that suffered a humiliating demotion in status was the three-foot-long “baby sea serpent” captured in autumn 1817 in a field near the harbor of Cape Ann, north of Gloucester, Massachusetts, which had recently been the scene of numerous multiple-eyewitness sightings of an enormous snake-like sea monster that sometimes appeared humped. When the “baby” specimen was captured, it was deemed by a committee of scientists from the Linnaean Society of New England to be a young specimen of the monster that had lately visited Cape Ann, and was duly christened

Scoliophis atlanticus

(“Atlantic humped snake”). When dissected and examined by fish researcher Alexandre Lesueur, however, it was revealed to be nothing more dramatic than a deformed specimen of a common American snake called the black racer

Coluber constrictor

.

One of the most popular “orthodox” zoological identities for sea serpents, especially some of the elongate, serpentiform versions, is the oarfish

Regalecus glesne

, and a number of snake-like carcasses washed ashore over the years have indeed proven to be specimens of this extraordinary creature. Its candidature as an identity for living sea serpents, conversely, has lately diminished thanks to a chance but quite remarkable discovery.

The world’s longest species of bony fish, the oarfish has traditionally been thought to swim horizontally, propelled via sinuous lateral undulations. As he revealed in an illustrated account published by the English magazine

BBC Wildlife

(June 1997), however, during a recent dive off Nassau, in the Bahamas, Brian Skerry was fortunate enough not only to encounter a living oarfish at close range, but also to photograph it. He was amazed to discover that it did not swim horizontally at all. Instead, it held its long thin body totally upright and perfectly rigid, with its pelvic rays splayed out to its sides to yield a cruciform outline, and it seemed to propel itself entirely via movements of its dorsal fin.

Oarfishes may swim horizontally too, but until now no one had ever suspected that this serpentine species could orient itself and move through the water in this odd, perpendicular fashion—a mode wholly distinct from the versions reported for elongate sea serpents.

Staying with elongate sea serpents: in February 1997, the central Philippine province of Masbate was the focus of intense cryptozoological interest, following the news that the carcass of a mysterious sea monster had been washed ashore here on Christmas Day 1996, in the coastal town of Claveria. According to press reports (e.g.

South China Morning Post

, February 25,1997), the carcass was of a 26-foot-long eel-like creature with a turtle-like head. A photograph of its preserved skull, vertebrae, and limbs appeared in the

Philippine Star

.

This photo, together with portions of its dried flesh, was presented to various unnamed experts for examination, but no one could identify them. According to Philippines University zoologist Dr. Perry Ong: “Judging from what I see now, it’s an eel-like fish.

It must be an ancestral or primitive fish. It had fins. But if it’s a fish, where are the ribs? It is not a mammal.” Curiously, however, its head apparently possessed a blowhole-like orifice, resembling that of a dolphin, though it lacked the latter’s familiar elongate beak (rostrum). My own opinion is that it was probably a highly decomposed killer whale

Orcinus orca

.

Perhaps the most mystifying aspect of all concerned the alleged suggestion by some “scientists” that its bones should be carbon-dated: “to determine if the animal is prehistoric.” Yet as the creature evidently died only very recently, as evinced, for instance, by the presence of dried flesh still attached to its carcass, it is clearly not prehistoric. So why on Earth would any scientist propose carbon-dating it? Since this brief burst of media interest, no further news has emerged regarding the Masbate monster or the fate of its carcass.

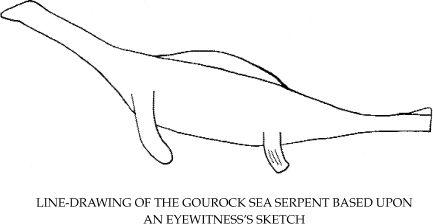

The history of cryptozoology is embarrassingly well supplied with classic cases of lost opportunities, and the long-running saga of the sea serpents has provided quite a number of these over the years. One of the most notable examples took place on the shores of Gourock, on Scotland’s River Clyde. This was where, in summer 1942, an intriguing (if odiferous!) carcass was stranded that was closely observed by council officer Charles Rankin.

Measuring 27 to 28 feet long, it had a lengthy neck, a relatively small flattened head with a sharp muzzle and prominent eyebrow ridges, large pointed teeth in each jaw, rather large laterally sited eyes, a long rectangular tail that seemed to have been vertical in life, and two pairs of L-shaped flippers (of which the front pair were the larger, and the back pair the broader). Curiously, its body did not appear to contain any bones other than its spinal column, but its smooth skin bore many six-inch-long bristle-like “hairs” resembling steel knitting needles in form and thickness but more flexible.

Rankin was naturally very curious to learn what this strange creature could be, whose remains resembled those of a huge lizard in his opinion. But as World War II was well underway and this locality had been classed as a restricted area, he was not permitted to take any photographs of it, and scientists who might otherwise have shown an interest were presumably occupied with wartime work. Consequently, this mystery beast’s carcass was summarily disposed of—hacked into pieces, and buried in grounds that have since been converted into a football pitch. All that remained to verify its existence was one of its strange “knitting needle” bristles, which Rankin had pulled out of a flipper and kept in his desk, where it eventually shriveled until it resembled a coiled spring.