The Beasts that Hide from Man (14 page)

Read The Beasts that Hide from Man Online

Authors: Karl P.N. Shuker

I am exceedingly grateful to the late John Edwards Hill, bat specialist and formerly Principal Scientific Officer at the British Museum (Natural History), who presented me with a great deal of information that offers a completely different outlook upon this perplexing case. It is well known that the New World vampire bats transmit livestock diseases from one animal victim to another, in a manner paralleling the activities of mosquitoes and other sanguinivorous insect vectors. They also carry rabies to man, though this is a much rarer occurrence than the more lurid reports in the popular press would have us believe. Moreover, bats of many species all around the world are known to contract many different types of bacterial, viral, and protozoan diseases, which can be spread to other organisms via parasites such as body lice and ticks that live upon the bats’ skin or fur. Relapsing fever in man, for example, is caused by the bacterium

Borrelia recurrentis

, carried by lice and ticks that have in turn derived it from former rodent or bat hosts.

Accordingly, during our communications concerning the death bird, Hill suggested that it is possible that humans venturing in or near a cave heavily infested with bats (like Devil’s Cave, for instance) would become infected with such diseases—if lice or ticks, dropping from the bats as they flew overhead, bit the unfortunate humans upon which they landed. A parasite-borne infection of this nature would account for the bite-like wounds of the goatherds observed by de Prorok; and, depending upon the precise type of infection, could ultimately give rise to the emaciated condition exhibited by these afflicted persons.

Additionally, native superstition and a deep-rooted fear of bats might be sufficient, when coupled with the distressing effects of a parasite-borne infection, to nurture the belief among such poorly educated people as these that they were the victims of blood-sucking bats—the notion of vampirism is very ancient and widespread in human cultures worldwide (the Maya of pre-Columbian Mesoamerica even worshipped the vampire bat as a god named Camazotz).

Two other medical explanations for the death bird case were also raised by Hill during our correspondence (though he rated both of these as being less plausible than the likelihood of a parasite-borne disease’s involvement).

As Devil’s Cave contained large quantities of bat excrement, perhaps these droppings harbored the spores of the soil fungus

Histoplasma capsulatum

(even though this is more usually associated with bird guano); if inhaled, these spores can cause an infection of the lungs known as histoplasmosis, which

can

prove fatal (but severe cases are not common).

Alternatively, an illness called Weil’s disease also offers some notable parallels with the “death bird syndrome.” Also referred to as epidemic spirochaetal jaundice and as leptospirosis icterohaemorrhagica, Weil’s disease is caused by spirochaete bacteria of the genus

Leptospira

, and is usually spread by rodents, but the bacteria have been found in a few species of bat as well. Infection generally occurs through infected drinking water, and among the ensuing symptoms of contraction is the appearance of small hemorrhages in the skin, which could be mistaken for bites. Also, the accompanying damage to the kidneys and liver, jaundice, and overall malaise experienced by sufferers could explain the goatherds’ haggard, wasted form.

Clearly, then, the case of the dreaded death bird and the stricken herders is far from being as straightforward as it seemed on first sight, and may involve any one, or perhaps even more than one, of the above solutions. An aspect of the case that is self-evident, however, is the necessity for a specimen of the death bird to be collected and formally studied. Only then might the resolution of this mystifying and macabre cryptozoological riddle be finally achieved—but in view of the perennially uncertain political climate associated with Ethiopia in modern times, even this is unlikely to prove an easy task to accomplish.

Until then, the secret of this purportedly deadly unidentified creature will remain as dark and impenetrable as the grim cave from which its winged minions allegedly issue forth each night to perform their vile abominations upon the latest tragic campful of doomed, defenseless goatherds.

SASABONSAM

SCULPTURE

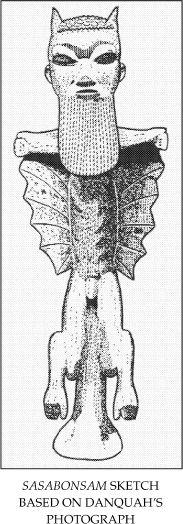

One particularly bizarre entity deserves brief mention here if only because it is as likely to have been inspired by encounters with strange bats as by anything else. In an absorbing

West African Review

article for September 1939, J.B. Danquah included a photograph of a carving produced by a member of Ghana’s Asantehene people, which depicted a grotesque being—referred to as the

sasabonsam

. According to the carving, the

sasabonsam

has a human face with a broad, lengthy beard, long hair, and two horns or pointed ears; an extremely thin body with readily visible ribs; short stubby forelimbs that, when lifted upwards, reveal a pair of thin membranes resembling a bat’s wings; and long, twisted legs terminating in feet with distinct toes. Most authorities dismiss this creature as a myth, but a few have wondered whether it could be some form of giant bat.

Of particular interest to Danquah was the narrative of a youth present in a crowd of people (which included Danquah himself) observing this carving being photographed, because the youth averred that once, at his own Ashanti town, he had seen the body of a

sasabonsam

—killed by a man called Agya Wuo, who had brought its carcass into the town. The youth confirmed that the carving was very like the

sasabonsam

that he had seen, and he added some details based upon the dead specimen.

This had been more than five and a half feet tall; its wings were very thin but when fully stretched out could yield a span of up to 20 feet; its arms (unlike the carving’s) were very long, as were its teeth; its skin was spotted black and white; and there had been scaly ridges over its eyes, with hard, stiff hair on its head. The man who had killed it had stated that he had encountered it sleeping in a tree hollow, and that it had emitted a cry like that of a bat but deeper. The body was allegedly taken to the bungalow of L.W. Wood, the region’s District Commissioner, who photographed it on February 22,1928.

Danquah later contacted Wood, who seemed uncertain whether he had indeed photographed such a creature; in addition, he claimed that although he was in Ashanti in February 1918, he was not there in February 1928. It is possible, therefore, that if this account is true, the youth who informed Danquah had become confused regarding the date.

In any event, neither the carving nor the description of the dead specimen bear more than the most passing of resemblances to a bat—but it is equally true that they do not call to mind any other type of animal either! If the fate of the dead specimen (always assuming of course that there really was such a specimen) could be ascertained, its skeleton would solve the currently insoluble riddle of the

sasabonsam s

identity—but until then, this “bat with a beard” must remain just another one of the varied beings of African mythology that appear to have no known counterpart in the zoological world.

Seram (also spelled “Ceram”) is the second largest island of the Moluccas group in eastern Indonesia, west of New Guinea, but the dense rainforests occupying its interior are still largely unexplored—which is why the following communication to me from cryptozoological explorer Bill Gibbons is one of the most remarkable that I have ever received. I am very grateful to Bill, formerly of the U.K. but now living in Canada, for sharing this data with me, and permitting me to document it here.

It was gathered by one of Bill’s colleagues, tropical agriculturalist Tyson Hughes, who visited Seram in June 1986, working there for the VSO (Voluntary Service Overseas) as the project manager of a model farm with 16 staff members. According to Bill’s communication to me:

During his free time, Tyson became interested in native accounts of a bizarre creature known as the Orang Bati, meaning ‘flying men’ in Indonesian. The villagers of the coastal regions live in literal terror of the Orang Bati, which, they claim, live in the interior of long-dead volcanic mountains. At night the Orang Bati will leave their mountain lairs and fly across the jungles to the coast, where they seize human victims from the coastal villages and carry them back to the mountains.

Although the local police are aware of the native accounts of the Orang Bati, they dismiss them out of hand, mocking any reports that filter their way into civilisation. The majority of serving police officers are actually Javan, so their skepticism is, perhaps, not unexpected. However, the fear of the Orang Bati is considerable among almost all the indigenous inhabitants of Seram Island. Those abducted by the Orang Bati are never seen again. These mysterious creatures are described as human in form, with red coloured skin, black wings, and long, thin tails. Tyson was able to persuade several village hunters to lead him through a dense area of jungle towards the alleged lair of the Orang Bati. Although he became the first white man to explore part of Seram Island, the Orang Bati remained elusive.

In a later letter to me, Bill added that the

orang bati

emits a long, mournful wail, is four feet to five feet tall, prefers to abduct infants and children, and terrorizes the coastal village of Uraur among others. He also noted that there do not appear to be any monkeys on Seram—which, if true, could explain why it preys upon human youngsters.

On first sight, if we assume that the

orang bati

is indeed real and not a figment of superstition-inflated imagination, the most reasonable solution to the mystery of its identity is to nominate the existence of a scientifically unrecorded species of giant bat— though any bat large and powerful enough to abduct children would be both a marvel and a monster.

However, an even more radical, controversial comparison vigorously vies for my attention whenever I attempt to reconcile the

orang bati

with the identity of a giant bat. According to the testimony of three U.S. Marines, one of whom was Earl Morrison, while on guard duty near Da Nang in South Vietnam during summer 1969 they spied a mysterious entity flying slowly towards them that possessed bat-like wings, but it was far larger than any normal bat. As it came nearer, the trio realized to their amazement that this bizarre being resembled a naked woman about five feet tall, with black furry skin and black wings—to which were attached her arms, hands, and fingers. After “she” had flown overhead, and traveled about 10 feet beyond them, the men could hear her wings flapping.

Inevitably but not unreasonably, this report has been dismissed in the past by skeptics as a misidentification of some large species of bird, or bat, resulting from long-term stress induced by living in a war zone. In view of the

orang bati

, however, the time may have come to re-examine this mystifying account from southeast Asia in a new light.

Few creatures are likely to stay hidden from human interference as effectively as those that are nocturnal, winged, and capable of eliciting a profound degree of irrational fear and horror in mankind. Little wonder, therefore, that bats remain some of the most mysterious mammals alive today, with new species appearing—and even supposedly extinct species reappearing—almost every year.

Consequently, the prospect that certain of the more remote, inhospitable reaches of the world could harbor very distinctive bats wholly unknown to science is really not very surprising—on the contrary, it would only be very surprising if this were

not

the case.

It may well be that there existed or still exists an unknown relatively large carnivorous plant that has one or two of the adaptations described for trapping birds or other smaller arboreal creatures. There are still large forest areas, especially in the southeastern and south-central portions of Madagascar, that would be interesting to explore

.R

OY

P. M

ACKAL

—

S

EARCHING

F

OR

H

IDDEN

A

NIMALS

WHEN THE VENUS FLYTRAP

DIONAEA MUSCIPULA

WAS first made known to botanists in the 1760s, they would not believe that it could actually catch and consume insects—until living specimens were observed in action. Moreover, reports have also emerged from several remote regions of the world concerning horrifying carnivorous plants that can ensnare and devour creatures as large as birds, dogs, and monkeys—and sometimes even humans! Once again, however, these accounts have been received with great skepticism by science—relegating them to the realms of fantasy alongside such fictitious flora as Audrey II, the bloodthirsty “Green Mean Mother” star of the cult movie musical

Little Shop of Horrors

(1986). But could such botanical nightmares really exist? Examine the following selection of remarkable reports, and judge for yourself.