The Attacking Ocean (15 page)

Read The Attacking Ocean Online

Authors: Brian Fagan

Tags: #The Past, #Present, #and Future of Rising Sea Levels

By Homer’s time, maritime trade was big business in the Aegean Sea. Much of this commerce passed from village to village and bay to bay along the Turkish and Levantine coasts, with dozens of places of refuge

within relatively easy reach, a few of them artificial ports built by human hands. The small port town of Phalasarna in extreme western Crete is a case in point. Three small islands protected the settlement, at a strategic location close to the eastern end of Crete and major trade routes. A rocky cape still provides shelter and good anchorage, with massive fortifications at the foot of the point. Immediately south of the fortifications once lay an artificial harbor accessible through two long canals, which are now dry. The port and canals have risen between six and nine meters as part of a general uplifting of western Crete, perhaps as a result of a major earthquake that struck the region about 365 C.E.

Figure 6.2

Locations in

chapter 6

.

The earliest recorded settlement at Phalasarna belongs to the Minoans. According to a much later

periplus

(sailing directions) of about 350 B.C.E., the town, which by then was minting its own coinage, was “a day’s sail from Lacedaemonia [the Peloponnese].” As late as the fourth century C.E., Phalasarna is said in another pilot book to have “a bay, a commercial harbor, and an old town.”

3

At least four watchtowers guarded the harbor. Excavations have shown that there was enough water in the channels and the harbor for a warship with a displacement of 1.5 meters. Characteristic notches made by waves in rocks at the side of the channels tell us that the sea was at minimum 6.5 meters above today’s sea level.

4

In 67 B.C.E. a Roman praetor (field commander), Caecilius Metellus, destroyed pirate strongholds along the Cretan coast, for the islanders were notorious brigands equipped with fast ships. There are signs that the Phalasarna channel was blocked with large boulders, perhaps as part of this exercise, for the port with its watchtowers was too small be a viable mercantile port of call. Metellus may have sacked the town, but in any case, its days were numbered when a great earthquake raised the coast, perhaps within a few days, and Phalasarna became high and dry.

HISSARLIK WAS NOT ALONE. Silting has been a persistent consequence of rising sea levels throughout the Mediterranean. Again, we have Strabo as an authority, who described the Piraeus, the port of classical Athens, as “formerly an island … [that] lay over against the mainland

from which it got the name it has.”

5

Long before Strabo, centuries of oral traditions treasured by the Athenians referred to the Piraeus as an island. We know that a shallow lagoon connected the rocky island to the mainland during the fifth century B.C., when the Athenian general Themistocles, and also the statesmen Cimon and Pericles, built two long walls that connected the city with its two harbors, one of them the Piraeus. The walls turned Athens into a fortress connected to the sea, its source of prosperity and military power. But was the Piraeus an island when the wall builders got to work, or did they fill in a shallow lagoon that separated what was then an islet from the mainland?

Clearly the original island formed as a result of sea level rise, quite easy to chronicle in an area where earthquakes are rare. A team of geologists drilled ten boreholes in a search for answers.

6

They recovered not only layers of shallow water marine deposits, but also shell species that document a gradual change from island to mainland. So we now know that Piraeus was an island in the center of a shallow marine bay between 4800 and 3400 B.C.E., when the first civilizations came into being in Egypt and Mesopotamia. From then until about 1500 B.C.E., a lagoon separated from the sea by beach barriers lay between Piraeus and the mainland. Silt from the Cephissus and Korydallos Rivers gradually filled in the lagoon. Exactly when Piraeus became part of the mainland is still unknown, but it was some time after 1000 B.C.E. and certainly well before the long walls were constructed. Strabo, relying on oral traditions and himself an experienced observer of landscapes, was absolutely correct, just as he was at Troy. Here, as in the Dardanelles, river silt had slowly undone what rising sea levels had wrought and made it possible to turn Athens into a fortress with safe access to the sea.

Silting may have helped Athens, but it caused major problems elsewhere. Miletus was a port in western Turkey encircled by mountains. Minoans from Crete traded here as early as 1400 B.C.E. According to Homer, some Miletans fought against the Greeks at Troy. By the seventh century, Miletus had established over ninety overseas colonies, one as far away as the Egyptian delta, another in the Black Sea. Miletus later became a Roman city and continued to flourish until the fourth century C.E., when silt brought down by the Meander River finally closed the

city’s harbors and turned them into a swamp. Without its ports, Miletus was dead.

Slave labor and improved engineering saw the construction of the first large artificial harbors in places where there was little or no natural shelter. Tyre and Sidon, the great Phoenician maritime city-states, lay on the present-day Lebanese coast. The Tyre area has suffered from subsidence since ancient times, with the Phoenician port’s northern breakwater lying about 2.5 meters below modern sea level. Here the water has risen at least 3.5 meters since classical times.

7

At Sidon, sea levels have been far more stable, with perhaps a rise of about half a meter. Thanks to core boring, we know something of the convoluted history of the two harbors. Between about 2000 and 1200 B.C.E., both cities relied on sheltered anchorages protected by natural promontories. Visiting ships lay in deep water, unloading their cargoes into smaller vessels to transport ashore. Sidon offered the somewhat better anchorage of the two, to the point that the city’s population grew and there may have been attempts to build a harbor.

During the first millennium B.C.E., so many ships arrived at Tyre and Sidon that the Phoenicians built artificial harbors at great expense. Almost immediately, both the semiprotected ports suffered from silting, so much so that in later centuries Roman and Byzantine authorities had to dredge the harbors. After Byzantine times, the two ports were all but abandoned as Tyre and Sidon lost commercial importance. Both silting and coastal buildup submerged the harbors, which were lost until modern times, when archaeologists rediscovered them.

Another humanly constructed port also suffered from both silting and natural disasters. Herod the Great founded Caesarea on the present-day Israeli coast with a totally artificial harbor, said by the historian Josephus to be larger than the Piraeus, on a coast devoid of natural shelter in about 25 to 13 B.C.E.

8

It became the civilian and military capital of Judaea Province. Two moles of cemented pozzolana protected the harbor, each set in a concrete foundation. The pozzolana, a form of volcanic ash, came from Italy and required at least forty-four shiploads of four hundred tons apiece. The breakwaters provided adequate protection even from severe storms. Unfortunately, however, the often poorly

mixed volcanic concrete did not bond well to rubble, which weakened them. Even worse, the port lay over a hidden geological fault line that runs along the coast. Earthquakes also ravaged the moles, causing them to tilt and settle into the seabed. Seabed studies have also shown that a tsunami attacked the area some time between the first and second centuries C.E. Whether this event merely damaged the harbor or destroyed it is unknown, but by the sixth century the harbor was silted up and unusable. Today, Herod’s moles lie over five meters underwater.

THE ROMANS WERE industrious builders of harbors of all kinds. There were at least 240 major Roman ports in the eastern Mediterranean and around 1,870 in the west. Many such havens lay behind the coast on lagoons, in rivers, or even in canals.

9

Since most Roman ships were relatively small and rarely drew more than two meters, ports for even quite large cities could be small and shallow. Where there were no sheltered bays or natural anchorages as there were in the Aegean and Adriatic, the Romans turned to artificial harbors, built with slave labor. Their engineers had to confront the problem of silt, brought to the ocean by rivers large and small, then distributed counterclockwise by the Mediterranean current. For this reason, the Romans built some ports to minimize silting, among them Alexandria, which rose on the more protected, western side of the Nile delta.

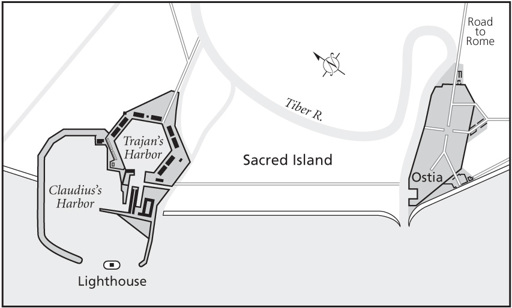

The imperial Roman harbors at Ostia, which serviced Rome, lay to the north of the Tiber River.

10

Over the centuries, silt moving up the coast from the river clogged the artificial ports, which now lie several kilometers inland. The first major harbor, known as Portus, built by Emperor Claudius in 42 C.E., lay on the northern mouths of the Tiber. Two hundred ships sank here during a tsunami fourteen years later. The first Portus was not only vulnerable but also quick to silt up. Emperor Trajan finished a new harbor with a hexagonal shape capable of holding more than a hundred ships by 112 C.E. Ostia’s harbors declined and silted up as the city became a country retreat for wealthy citizens of Rome. They finally fell into disuse during the ninth century after repeated attacks by Arab pirates.

Figure 6.3

The ports at Ostia, Italy. Courtesy of Southampton University.

There were other harbors for Rome, too, all connected to the city by good roads. Each was a massive construction project. Pliny the Younger witnessed the building of Centumcellae harbor in the Bay of Naples by the Emperor Trajan, “where a natural bay is being converted with all speed into a harbor … At the entrance to the harbor an island is rising out of the water to act as a breakwater when the wind blows inland.” Barge after barge brought in large boulders cast into the water until they formed a “sort of rampart … Later on piers will be built on the stone foundation, and as time goes on it will look like a natural island.”

11

Trajan’s port is now Civitavecchia, a dreary cruise ship port for Rome.

THEN THERE IS VENICE, the poster child of subsidence and rising sea levels in the Mediterranean. Venice began as a series of lagoon communities, a trading place founded by the city of Padua during the fifth century C.E. The settlements allied with one another in mutual defense against the Lombards, as the Byzantine Empire’s influence dwindled. By the eighth century, Venice under its doges had become an important mercantile and shipbuilding center.

12

Soon Venice’s ships traded as far as the Ionian Sea and the Levantine coast. Venice became an independent city in 811. The city expanded closer to the Adriatic with canals, bridges, and fortifications, developing a close relationship with the ocean that was to endure for many centuries. Successive doges developed trade monopolies and acquired territories far from the Adriatic, with Venice reaching the height of its power in the fifteenth century. Despite constant wars and occasional reverses, Venice boasted of 180,000 inhabitants at the end of the fifteenth century, the second-largest city in Europe at the time, and certainly one of the richest in the world.

Over two million people lived under the Republic of Venice. Its wealth came from trade and shipbuilding, as well as fine textiles and jewelry, despite efforts by other powers to break its dominance in the eastern Mediterranean. The doges did everything they could to maintain strict neutrality between competing European monarchs. Venice remained wealthy, but coasted inexorably into slow decline, partly because of Portugal’s rising dominance of the Asian trade. To add to its afflictions, vicious plague epidemics killed thousands of Venetians, a third of the city’s population in 1630 alone. By the eighteenth century, the Adriatic was no longer a wholly Venetian world. Napoleon’s soldiers occupied much of the Venetian state. The city became part of the Austrian empire in 1797, and part of Italy in 1866. Today it is capital of Italy’s Veneto region, but only sixty thousand people live in the city itself.