The Attacking Ocean (17 page)

Read The Attacking Ocean Online

Authors: Brian Fagan

Tags: #The Past, #Present, #and Future of Rising Sea Levels

Most royal vineyards were in the delta, begun with imported grapevines. The first vintners were foreigners. Even in later centuries, many were Canaanites, who brought sophisticated methods to the business from the beginning. The blistering heat of the delta required irrigation for water-sensitive grapes, but fortunately the soil was rich alluvium, nourished by the Nile flood and salt-free. Millions of amphorae of red and white wine from delta vineyards supplied pharaohs and temples over the centuries and provided drink offerings at major religious ceremonies. Tomb paintings show workers stomping the vintage, holding on to vines to maintain their balance. In 1323 B.C.E., mourning officials provided the young pharaoh Tutankhamun with amphorae of fine red and white wines labeled with the location and the names of the vintners, most of them from the western delta.

6

The reputation, and acreage, of delta wines survived into Islamic times.

Fertile soils nourished with silt and floodwater, flushed of any trace of rising salinity by the inundation: Ta-Mehu (the ancient Egypt name

for the delta) was a patchwork of vineyards and productive cereal agriculture from very early times. The delta was Egypt’s exposed northern flank, subject to inundation and to incursions from the sea, in human terms a permeable northern frontier, sometimes fortified and used as a military base for strong rulers, at others occupied by invaders from what is now Libya or from the Levant. Ta-Mehu linked the pharaohs with the ocean and the wider world beyond the horizon.

The pharaohs’ greatest wealth was from agriculture, from the crops grown using the ideal natural cycle of the great river, much of the harvest coming from the delta. For more than three thousand years, the life-giving waters of the Nile defined ancient Egyptian life from the First Cataract to the Mediterranean. The river was an artery for transport and communication, the source of agricultural bounty, and it supported rich fisheries. Hardly surprisingly, the pharaohs developed a complex ideology that centered on the river and its annual inundation. Creation myths spoke of the waters of Nun, which receded to reveal a primordial mound, just like the floodplain emerging from the retreating inundation. The creator god Atum appeared at the same moment and sat on the emerging tumulus. It was he who was the first living being, who created order from chaos—just like every pharaoh who presided over the Two Lands.

In Ta-Mehu, as elsewhere in Egypt, three seasons defined the year: Akhet, the inundation, Peret, growing, and Shemu, drought.

7

The natural cycle of the Nile governed all attempts to cultivate the delta. Akhet provided life-giving water and silt, although human ingenuity could do much to improve the watering of the land. Farmers raised earthen banks to enclose large flood basins where they could retain water before releasing it. This was irrigation at its simplest, but it was usually sufficient to feed the four million to five million Egyptians who lived along the river at the height of the pharaohs’ power during the second millennium B.C.E. There was no talk of cash crops in a self-sufficient agricultural economy. Such a notion was unthinkable to the pharaohs and their subjects. A small army of officials and scribes oversaw agriculture throughout the kingdom, but their interest was not in the nuances of farming, but purely in carefully documented yields for rents and taxes. For many centuries, ancient Egyptian villages fed the kingdom.

Farmers living in the delta may have labored in royal or temple estates as well as in village fields. There was generally enough to eat, crop yields were usually, but not invariably, more than adequate, and there was slow population growth with little or no threat from rising sea levels. Barrier dunes, extensive lagoons and marshes, and thick mangrove swamps served as natural fortifications for the farming landscape farther inland during thousands of years of very minor sea level change—most of that which did occur resulted from subsidence caused by earth movements.

WE SHOULD EMBARK on a minor environmental tangent here, for wetlands and marshes are important players in coastal protection in many parts of the world.

8

Wetlands are part of both aquatic and terrestrial environments. They are most widespread along low-lying coasts, such as those of the Florida Everglades, the Mississippi delta, or the delta shores of Bangladesh in South Asia. Like wetlands, freshwater and salt marshes are highly productive and often biologically diverse. Both provide invaluable protection against coastal erosion as well as providing excellent habitats for birds, fish, shrimp, and other organisms.

Salt marshes, flooded each high tide, have less biological diversity, for few plants can tolerate saltwater. They also trap pollutants flowing toward the shore from upstream and provide nutrients to surrounding waters. Being constantly inundated by rising tides, they are well adapted to rising sea levels. In the natural course of events, the marsh surface rises each year through the natural accumulation of sediments. At the same time, they also creep inland as sea level rises, maintaining themselves as the landscape changes, just as barrier islands do. Thus, they offer excellent natural coastal protection where the topography permits inland creep, provided agriculture and building do not destroy them, as now happens increasingly all over the world. Modern-day seawalls and other coastal defenses limit marsh expansion in estuaries, a chronic occurrence along the East Coast of the United States with its proliferation of coastal vacation properties. The destruction and especially restriction of inland expansion of marshes and wetlands have deprived us of vital coastal protection.

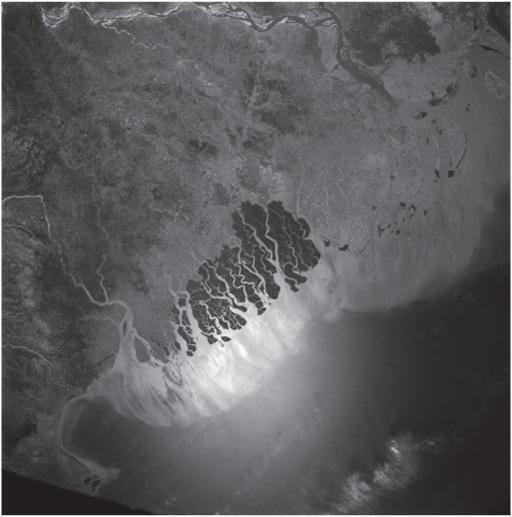

Figure 7.1

Sundarban mangrove swamps (dark areas) lie at the mouth of the Ganges River in Bangladesh. Taken from the space shuttle

Columbia

on March 9, 1994. Courtesy: NASA.

Mangroves protect coastlines over an enormous swath of the tropical world, including the Nile delta, in areas where waves are low and often where coral reefs protect them. Dense belts of them offer superb coastal protection, as the inhabitants of Homestead, Florida, discovered in 1992, when Hurricane Andrew’s waves harmlessly surged into mangroves that protected the town. Mangroves also saved the Ranong area of Thailand from the great tsunami of 2004, which killed numerous victims in neighboring areas where the mangroves had been cleared (see

chapter 10

). Brazil is home to 15 percent of all mangrove habitats, but they line between

60 and 70 percent of tropical coastlines, or did until the twentieth century. Different mangrove species inhabit the diverse zones of coastal habitats, each growing at the limits of its tolerance for salinity. As the oceans warm, we can expect mangrove swamps to expand northward and southward from their present ranges, which is good news, for they nurture numerous species of birds, fish, reptiles, and shellfish. In Bangladesh, they were home to tigers. In Brazil and Colombia jaguars hunt prey at the edge of mangrove swamps.

For all their usefulness, mangrove thickets deter people with their tangled vegetation, numerous snakes, and endemic mosquitoes. They have inevitably become a target for destruction, cleared for agriculture and aquaculture, used as a source for house timber, a centuries-old industry in East Africa, whose swamps provided wood for houses in treeless Arabia. Today, the greatest threat to mangrove swamps comes from aquaculture, especially shrimp farming, which is a huge international industry in poverty-stricken countries like Bangladesh, Ecuador, and Honduras. Fortunately, mangroves are in no danger of extinction, for they are capable of adjusting effortlessly to sea level changes. Their greatest threat comes from humanity. We seem unaware that mangroves, marshes, and wetlands are some of our best weapons against onslaughts from the ocean.

BACK TO THE NILE: During the first millennium C.E., the delta rose to political and economic prominence, thanks to its burgeoning links with Greece, Rome, and other easily accessible, powerful kingdoms beyond Egypt’s boundaries. The political equation changed decisively with the founding of Alexandria on the delta coast in 331 B.C.E., which brought the entire Mediterranean world to Egypt’s doorstep. Much of the prosperity stayed downstream at a time when the diverse mouths of the Nile shifted and shifted again as a result of earthquake activity, subsidence, and coastal erosion. As was always the case until camel caravans became commonplace, most trade into the Nile valley traveled up the river. The delta beyond its growing cities and ports still remained somewhat of an agricultural backwater, despite its rich soils and excellent

taxation potential, for there was negligible population pressure by modern standards. An estimated three hundred thousand people lived in Alexandria at the time of Christ, some half a million in Cairo a thousand years later, a medieval city that, thanks to Mamluk rulers, became a prosperous camel caravan meeting place after the thirteenth century and soon overshadowed the coastal city.

There was still plenty of cultivable and taxable land in the delta after Cairo rose to prominence. Repeated plague epidemics kept population growth in check, so it was still easy to adjust to sea level changes and coastal subsidence. Today the delta is so densely populated that there is not enough land to go around and the ocean is moving inland. Compare the medieval figures of 300,000 and 500,000 people with those for 2011: Over 3.8 million people crowd into modern Alexandria, while Cairo with its over 6 million urban inhabitants has a staggering population density of 17,190 people per square kilometer, one of the most densely populated cities in the world, this before one factors in the surrounding suburbs. The soaring urban and rural populations of both the delta and Upper Egypt have brought the complex relationship between the Nile and the ocean to the brink of crisis.

The present delta crisis has its origins in the early nineteenth century, when the Mamluk Muhammad Ali Pasha, well aware of the economic potential of Lower Egypt’s soils, decided to increase cotton production in the delta, cotton being a lucrative cash crop. Ali deployed forced labor from villages along the Nile in an orgy of deep canal digging.

9

His ruthless practices and the ambitious, often unsuccessful projects of his successors resulted in massive international debts and a breakdown of political order that led to British occupation in 1882. The new occupiers in turn invested heavily in irrigation agriculture both as a way of paying off foreign creditors and to feed a burgeoning population, over seven million in 1882 and up to eleven million by 1907. Even with these investments, there was insufficient inundation water to go around. The British consul general, Lord Cromer, laid plans for a network of dams and barrages to expand irrigation and to reduce dependency on unpredictable floodwaters.

His timing was impeccable politically. By this time, epic Victorian

explorations had traced the Nile to its multiple sources. Furthermore, the British controlled the entire length of the river except the upper reaches in Ethiopia, so long-term planning and major dams were practicable for the first time. The so-called Aswan Low Dam was constructed immediately below the First Cataract between 1898 and 1907, with numerous gates to allow both water and silt to pass through.

10

The dam was too low, so it was raised twice, in 1907–1912 and again in 1929–1933, giving it a crest thirty-six meters above the original riverbed. Even that was not enough. After the inundation nearly topped the dam in 1946, the British decided to build a second dam about seven kilometers upstream. Changing political circumstances and international maneuvering delayed construction until 1960–1976. The massive rock-and-clay Aswan Dam, 111 meters tall and nearly 4 kilometers from bank to bank, truly blocked the river, forming Lake Nasser, a huge reservoir 550 kilometers long.

11

Spillways allow a constant flow of water through the barrier, so the Nile is no longer a natural watercourse but effectively a huge irrigation channel. Instead of overflowing its banks, the river remains at the same level year-round.

The Aswan Dam protects Egypt from floods and the immediate effects of drought, but the long-term environmental consequences are only now beginning to come into focus. In predam days, when the Nile flooded, the low groundwater level when evaporation was highest in summer prevented salt rising to the surface through capillary action. Now the groundwater level is higher and more constant natural flushing has virtually ceased. As a result, soil salinity has increased dramatically, endangering agricultural yields. Only now are large-scale, and extremely expensive, drainage schemes attempting to take care of the problem. Before the Aswan Dam, 88 percent of the silt carried downstream ended up in the delta. Now 98 percent of the silt load remains above the dam and virtually no silt reaches the ocean. Chemical fertilizers have replaced silt; diesel pumps rather than gravity provide irrigation water year-round. Some years the authorities close off the dam for two or three weeks in winter. Far downstream, the surviving delta lake levels fall rapidly; sea-water promptly enters them.