The Attacking Ocean (14 page)

Read The Attacking Ocean Online

Authors: Brian Fagan

Tags: #The Past, #Present, #and Future of Rising Sea Levels

Building seawalls and dikes was one thing; maintaining them was another. Lethargic farming communities neglected their own water defenses, perhaps in a fatalistic belief that they were doomed to suffer God’s anger. At the back of every Christian’s mind lurked the terrible image of the Last Judgment, “when the revelation of that day will be very terrible to all created things.”

12

Much of the time, instead of banding together, farmers and landowners wrangled constantly over the cost of maintaining dikes and did nothing. Inevitably, neglected sea defenses fell into disrepair; inevitably, too, unpredictable floods destroyed whole villages and killed entire families.

Unbeknownst to the quarreling farmers and landowners, who knew nothing of the wider world, the great sea surges originated with the strong winds generated by extratropical cyclones far out in the Atlantic. Such tempests covered an enormous area; gale-force winds blew over

hundreds of kilometers of ocean. The surges that beset them and still beset the North Sea typically originated in storms off northern Britain. They moved southward along the eastern shores of Scotland and England and up the Thames River. Intense low pressure and strong northerly winds drove the North Sea’s surface waters southward into the narrowing sea basin, piling up water in vicious assaults against the Low Countries.

13

The most destructive storm surges coincided with unusually high spring tides, when incoming seawater flowed far inland, checking the discharge of freshwater from higher ground. Violent waves and scouring tides would sweep ashore carrying everything before them, causing human tragedies that would assume almost mythic status in folk memory.

We know of major floods from at least three violent storm surges that hit the German and Dutch coasts in about 1200, 1219, and 1287.

14

The surge of January 16, 1219, the feast day of St. Marcellus, killed at least thirty-six thousand people. By bizarre coincidence, one of the greatest and best known medieval surges, known as the Grote Mandrenke (the Great Killing of Men) of 1362, struck on the same day as the 1219 cataclysm:

“Then on the morrow of Saint Martin … there burst forth suddenly at night extraordinary inundations of the sea, and a very strong wind was heard at the same time as unusually great waves of the sea. Especially in places by the sea, the wind tore up anchors and deprived ports of their fleets, drowned a multitude of men, wiped out flocks of sheep and herds of cows … an infinity of people perished, so that in one not particularly populous township in one day a hundred bodies were given over to a grievous tomb.”

15

The Grote Mandrenke originated as a severe southwesterly gale in the Atlantic. Storm winds swept across Ireland, then England, where houses collapsed and the wooden spire of Norwich cathedral fell through the roof below. Across the North Sea, the gale descended on the Low Countries and northern Germany at high tide. Wind and waves wiped out sixty parishes in coastal Denmark and widened the entrance of the Zuiderzee to the ocean. This was the only positive outcome of the disaster. Once stabilized by dikes, the new inlet became a major hub

of maritime trade for the later Dutch Empire. A huge sea surge swamped harbors and landing places without warning. The wealthy port of Rungholt on the island of Strand in Schleswig-Holstein, northern Germany, vanished below the waves. Over half of Strand’s population drowned.

16

On the opposite side of the North Sea, a trading village, Ravenser Odd at the mouth of the Humber River on the Yorkshire coast, also disappeared. The inevitable stories of ringing church bells below the waves heard by passing sailors persisted, as if the sea surge resulted from divine wrath. A minimum of twenty-five thousand people, certainly many more, perished in the Great Drowning.

Storm surges were even more frequent between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries, such as the apocalyptic St. Elizabeth’s flood of November 1421. Persistently stronger winds moved coastal dunes several kilometers inshore from Texel in the north to Walcheren to the south. Only since the fifteenth century has the building of large breakwaters on the foreshore and the planting of grasses and trees on the dunes slowed the process. The destruction was cumulative but immense. For instance, the church at Egmond, an important agricultural settlement, lay in the lee of the dunes in 1570. The dunes moved beyond the church, leaving it exposed, until it fell victim to the North Sea in 1741.

By the end of the Middle Ages, intricate rings and lines of dikes, also river embankments and dams, formed a measure of coastal protection, but not nearly enough for a region of growing cities and rising population. A confusing mélange of dike, drainage, and supervisory boards oversaw the work, which fostered powerful notions of independence and self-government, and also of service for the common good, quite independent of feudal lords—something radically new. Major landowners now offered incentives such as low rent or free status to anyone willing to settle in such flood-prone areas.

Land reclamation had also lowered the level of peat surfaces over hundreds of square kilometers. The authorities outlawed turf cutting as part of peat digging for salt extraction within a few kilometers of dikes in 1404, on the grounds that it seriously undermined sea defenses.

17

Many rivers now flowed above adjacent lands, making it easier for floodwaters

to breach the dikes. Rising water tables had turned much agricultural land into waterlogged pasture or hay meadows. With only gravity to rely on, draining the inundated land often proved near impossible. Land reclamation now came into play on a much larger scale.

The Grote Waard, south of the modern city of Dordrecht, became the most highly developed reclamation project.

18

Once a swampy waste, with small villages on higher ridges linked by dikes that served as tracks, Dirk III, Count of Holland, seized the land during the eleventh century. By 1300, his successors had dammed the main streams and built a ring of dikes. A century later, over forty villages sent grain, turf, and salt to Dordrecht’s markets from a single great polder covering some fifty thousand hectares.

19

(A polder is a tract of reclaimed land protected by a dike.) But the Grote Waard carried the seeds of its own destruction. The poorly maintained, often undermined dikes built on unconsolidated peat collapsed on themselves if built up too high. Much of the reclaimed land lay at a vulnerable spot, where floods could attack it on two sides, both from the North Sea and from the waters of great rivers like the Maas, Rhine, and Waal. Years of major surges had breached the dikes again and again throughout the fourteenth century, but the farmers repaired the damage and drained the land anew. Then a major inundation in 1420 destroyed all the records of the water board and disrupted its administration at a time of major political strife.

A year later, on the night of St. Elizabeth’s Day, November 18–19, 1421, fierce westerly winds coincided with an exceptionally high tide, breached the dikes, and inundated the Grote Waard when the Maas and Waal Rivers were at high flood levels. The rising seawater burst dikes on another side of the Waard. The raging water flowed strongly to the southwest through a natural drainage, creating a channel now called Hollands Deep. Much of the Waard rapidly became shallow lakes or tidal waterways. At least twenty villages vanished and ten thousand people died, shattering community life. The once-prosperous city of Dordrecht, which thrived off the great polder, now stood on a tiny island. The disaster reduced many, including the local nobility, to penury. Anarchy descended on the surrounding countryside as raiders plundered granaries.

The Grote Waard had vanished beyond any hope of restoration. In its place was a wide area of open water. Generations passed before some limited reclamation work on its margins began.

Ultimately, the lack of an effective technology for land drainage and reclamation defeated the farmers, who had to drain their lands with gravity, scoops, or waterwheels. Salvation in the long term came with the invention of the wind-driven water mills and pumps, around 1408. Two centuries were to pass before such devices came into widespread use and ushered in the modern era of coastal sea defenses in the Netherlands.

Life along the North Sea shore was a constant tussle against the ocean, not so much against rising sea levels as attacks by unpredictable sea surges that coincided with exceptionally high tides. The farmers fought the attacking sea by armoring the coast with dikes and earthworks, the only viable defense in these landscapes. Human hands and backbreaking labor were often inadequate to the task, but humanly made sea defenses were the only long-term strategy for cities and towns at or near sea level. Armoring shorelines remains the strategy of choice against rising seas in many parts of the world. Twenty-first-century technology allows us to fence off the land at vast expense on a scale unimaginable even a century ago. The costs are gargantuan, beyond the purses of many endangered lands—and there is no guarantee that armoring will ultimately work.

By about 5000 B.C.E., Mediterranean sea levels had basically stabilized after the tumult of the Ice Age melt. Some adjustments to higher sea levels continued to persist, especially as rivers’ flows became more sluggish and silt brought down by spring floods accumulated on coastal floodplains rather than being carried offshore into deep water. From the human perspective, the Mediterranean was, for all intents and purposes, a huge lake. The historian Fernand Braudel once called it a “sea of seas,” where coastal trade in commodities and objects both rare and prosaic thrived. As early as the late tenth millennium B.C.E., farmers were crossing from Turkey to Cyprus. By 2000 B.C.E., hundreds of ships large and small plied eastern Mediterranean shores. The Minoans of Crete and the Mycenaeans of southern Greece were some of the most accomplished of these traders. And it was sailors from these ancient seafaring traditions that carried Greek warriors to Troy (also commonly known as Hissarlik) for the legendary siege immortalized by Homer in

The Iliad

, perhaps around 1200 B.C.E. But where did they land? Rising sea levels and the silting resulting from them, as well as earthquake activity, have altered coastal landscapes throughout the eastern Mediterranean beyond recognition.

Homer gives us the only description of the Achaean harbor during the siege of Troy, in about the twelfth century B.C.E.

[The Greek ships] were drawn up some way from where the fighting was going on, being on the shore itself inasmuch as they had been beached first, while the wall had been built behind the hinder-most. The stretch of the shore, wide though it was, did not afford room for all the ships, and the host was cramped for space, therefore they had placed the ships in rows one behind the other, and had filled the whole opening of the bay between the two points that formed it.

1

Scholars have argued over the geography of the Trojan plain and the location of the Greek camp for over two thousand years. The Greek geographer Strabo wrote that “the Simoeis and Scamander [Rivers] effect a confluence in the plain, and since they bring down a great quantity of silt they advance the coastline.”

2

Strabo pointed out that the coastline in his day was twice as far from the city as it had been twelve hundred years earlier during Homeric times. Today the shallow bay below Hissarlik is dry land.

Both the Simoeis and Scamander would have had steep gradients during the late Ice Age, when sea levels were much lower. As the ocean climbed with global warming, so the river gradients became shallower, just as they did along the Nile. Riverborne silt that had once flowed out

into the sea now arrived in the arms of much slower moving river floods. Instead of being pushed into deep water, the alluvium settled in shallow water. Currents in the Dardanelles also carried silt into the bay.

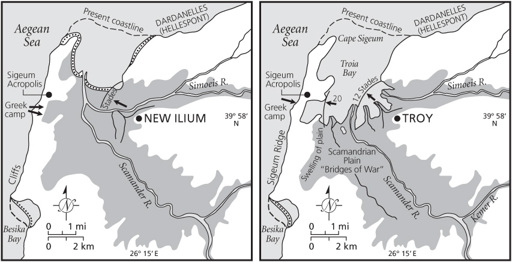

Figure 6.1

Rising sea levels at Hissarlik (Troy): (a) the environs of Troy in Strabo’s day and (b) the same area in Homeric times.

Core borings deep into the floodplain sediments have revealed details of the marine transgression that flooded the Trojan coastline after the Ice Age. Slowly accumulating clay and silt formed a delta floodplain. The cores show how the deepening silts slowly overrode the shallow marine muds that once filled what was, for a while, a bay and turned it into a plain. Constantly changing river channels dissected the new lowlands. Marshes expanded along the coastline, where sandy shoals close offshore protected the shoreline.

Comparing the geology with Homer’s epic and Strabo shows remarkable agreement, with the Homeric Troia Bay extending somewhat inland of Hissarlik, with a distance of about four kilometers from the besieged city to the Achaean encampment on the Cape Sigeum Peninsula to the west, where the Aegean becomes the Dardanelles.