The 30 Day MBA (41 page)

Authors: Colin Barrow

The idea that businesses had a responsibility other than to shareholders was brought to popular attention in Howard R Bowen's book

Social Responsibilities of the Businessman

(1953, New York: Harper and Brothers), but it was a decade later before the term âstakeholder' was coined in an internal memorandum at the Stanford Research Institute in 1963. Over the next two decades the term stakeholder was debated and defined until Edward Freeman, a professor at the Darden School of Business (

www.darden.virginia.edu

), University of Virginia, in his book

Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach

(1984, United States: Pitman Bowen), set out simple guidelines that anyone in an organization could understand and follow. Freeman's stakeholders were defined as âany group or individual who can affect or is affected by the achievement of the organization's objectives'.

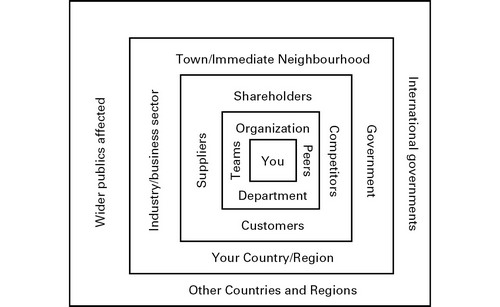

Freeman (see above) divided stakeholders into six distinct categories, owners, employees, customers, suppliers, communities and governments, with which an organization has varying responsibilities or âsocial contracts'. The first step in the process of developing an ethical strategy is to identify all the people, institutions and agencies that your organization is likely to impinge on in the normal course of its activities.

Figure 9.1

gives an example of a stakeholder map. It shows how stakeholders move outwards from the individual at the centre, to internal groups including their immediate work environment, colleagues, team and peers, and on to external groups, suppliers, customers, shareholders and eventually on to ever-distant publics and organizations.

FIGURE 9.1

Â

Stakeholder mapping

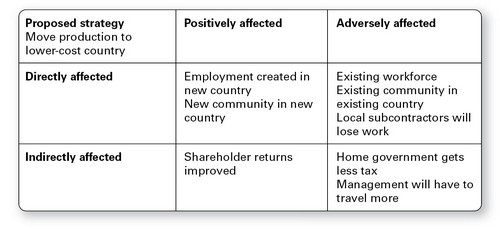

Not all stakeholders will be affected by any one particular strategy or course of action, nor will those that are affected be affected to the same degree. So the next step in the process is to see which stakeholders will be affected and to what degree. This can be done using a Stakeholder Relevance Matrix, as in

Figure 9.2

. This shows which stakeholder groups will be affected by the decision to relocate a production unit to a new lower-cost country.

FIGURE 9.2

Â

Stakeholder relevance matrix

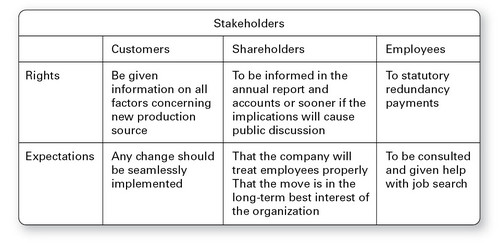

The next step in the process is to analyse the specific interests/expectations and rights/responsibilities of each affected stakeholder group. Following through with the example of relocating a factory, we can see in

Figure 9.3

the different expectations and rights of the three stakeholder groups seen to be most relevant to this decision.

FIGURE 9.3

Â

Stakeholder rights and expectations grid

Having identified the stakeholders and weighed up their rights and expectations, an organization has basically three possible ethical stances it can take:

- Immoral business: Make decisions that are clearly unethical to large groups of stakeholders. The Mafia and organized crime in general certainly fit into this category, as in many respects do the sex industry, large tracts of the gambling industry and arguably the tobacco and drinks industry too. These last three are accepted as

being a customer's inalienable right to free choice, aided by being major employers and taxpayers. - Amoral business: Make decisions without considering their ethical implications either through carelessness, indifference or the mistaken belief that business is there to make profit only. Such businesses see governments and their laws as the only ethical or moral constraint they need concern themselves with.

- Moral business: All decisions are made considering what is ethical, fair and just.

Implementing ethical and responsible strategies

Ethics and values play a central role in shaping a company's identity and reputation, building its brands, and earning the trust of customers, suppliers or other business partners. While honesty, fairness and responsibility are crucial for building a good reputation, an organization that is looking for pre-eminence in its field needs to go beyond just meeting stakeholders' needs. It has to emphasize the message that it is attractive as a business partner and as a good corporate citizen. To achieve this status the following steps need to be pursued:

- Acknowledge and monitor all stakeholders with a valid claim on your attentions.

- Communicate regularly with stakeholders, listening to their interests and concerns.

- Actively cooperate with stakeholders to minimize risks.

- Always avoid actions that endanger lives.

- Use processes that are sensitive to stakeholders' needs.

- Recognize the danger that managers' convenience and the needs of most other stakeholder groups will almost always be in conflict.

- Resolve stakeholder conflicts speedily and fairly.

Resolving conflict

Unfortunately, however ethical and socially responsible an organization is, it will at some stage, perhaps even frequently, find itself pursuing a strategy that upsets other stakeholder groups. A recent example of one such conflict was Shell's decision, announced in April 2008, to pull out of the London Array wind farm. This £2 billion project for 341 turbines capable of producing 1,000 megawatts of power was a key part of the UK government's strategy to produce 15 per cent of UK energy needs from renewable sources by 2015,

with an aspiration to raise that to 20 per cent by 2020. Given that in 2008 renewable energy accounted for only 2 per cent of output in the UK, the London Array was seen as important, perhaps vital, to achieving those goals. But Shell had to weigh up the consequences of upsetting the UK government, Friends of the Earth and its other German and Dutch partners in the project, with other concerns. Shell's view was that the cost of wind farms was simply spiralling out of control, with steel prices rising with increased world demand from such countries as China and India. In any event, world turbine production was booked up years in advance. Shell already had stakes in 11 wind farms producing over 1,100 megawatts and reckoned that as a company it could make the same contribution to the environment at a much lower cost to its shareholders, but probably on another continent and in another technology.

Resolving stakeholder conflicts calls for tact and communications and the recognition that while you can't please everyone, you can still be ethical. About 1 per cent of Shell's investments are in green projects. For example, a company subsidiary, Shell Solar, has played a major role in the development of first-generation CIS (copper indium diselenide) thin-film technology. This it believes to be the most commercially viable form of photovoltaic solar technology to generate electricity from the sun's energy. Together with its joint venture partner in this project, Saint Gobain, it has a pilot plant under construction in Saxony, Germany that will produce sufficient solar panels to save 14,000 tonnes of CO

2

per year. So stakeholders such as the UK government and Denmark's DONG Energy in the London Array project had to be weighed up against Saint Gobain, with the German government being party to both strategies through the participation of that country's energy giant, E.ON. All the while, Shell was under pressure to match its historic profit growth. Authenticity Consulting (

www.authenticityconsulting.com/misc/long.pdf

) has a useful checklist to help with decisions about resolving stakeholder conflict.

Whistle-blowers â an ethical longstop

Not surprisingly, the people most likely to know about unethical or socially irresponsible behaviour are those working in the organization itself. Governments around the world have adopted measures to encourage a flow of information on ethical problems and fraud from whistle-blowers â that is, anyone employed or recently employed by a public body, business organization or charity who reveals evidence of wrongdoing. Whistle-blowers have also been given a measure of legal protection. In the United States the LloydâLa Follette Act of 1912 started the ball rolling, giving federal employees the right to provide Congress with information, to be followed by a patchwork of laws covering such fields as water pollution, the environment, the SarbanesâOxley Act (2002) to deal with corporate fraud and the Whistleblower Protection Enhancement Act (2007). In the UK the Public Interest Disclosure Act (1998) and various laws enacted by the

European Union and other governments provide a framework of legal protection for individuals who disclose information.

Many firms too have established ways to attract information on frauds being committed against them, including 24-hour hotlines and corporate ethics offices. For example, Vodafone's (

www.vodafone.com/content/index/about/

about_us/suppliers/speak_up.html

) âSpeak Up' programme â launched in 2006/07â provides suppliers and employees working in its supply chain with a means of reporting any ethical concerns. Fewer than 10 incidents were reported in 2006/07. That low figure may be less to do with the absence of ethical problems and more to do with the deeply ingrained biases against whistle-blowing and a distrust of assurances that retribution will not follow, especially in areas far removed from the watchful eyes of a corporate ethics office.

These organizations can provide further background on the subject:

- The National Whistleblowers Centre (

www.whistleblowers.org

): Focuses on exposing government and corporate misconduct, promoting ethical standards and protecting the jobs and careers of whistle-blowers. - Spinwatch (

www.spinwatch.org

): Monitors the role of public relations and spin in contemporary society and has worked with whistle-blowers, anonymously, on some of the most contentious issues: Northern Ireland, the role of the media, genetic engineering, the oil industry, tobacco smuggling, food and farming, and the war in Iraq, for example. - Whistleblower (

www.whistleblower.co.uk

): Run by journalists and set up to allow people to sell stories to the media confidentially. It has had a measure of success, breaking the story on how the Richard and Judy Show's âYou Say, We Pay' competition was ripping off viewers. - The Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) has a factsheet on whistle-blowing at this weblink:

www.cipd.co.uk/hr-resources/factsheets/whistleblowing.aspx

.

There is plenty of anecdotal evidence that ethical and socially responsible organizations are better places to work. At the very least, being ethical provides an organization with an insurance policy limiting its exposure to a range of legal liabilities for faulty products, misleading advertising, price fixing and discrimination at work, for example. But evidence on whether being ethical helps a business organization to become and stay more profitable is less clear. Corpedia (

http://welcome.corpedia.com

), a compliance and ethics training company with clients in 60 countries, including RadioShack, EMC, Xerox and PepsiCo, produces an index of companies deemed ethical.

Companies such as Intel, Starbucks, The Timberland Company and Whole Foods Market are in its index, which it claims has outperformed the S&P 500 by more than 370 per cent over 5 years. The rather more scientific and comprehensive FTSE4Good Index Series (

www.ftse.com/Indices/FTSE4Good_Index_Series/Performance_Analysis.jsp

) also shows the ethical companies to be ahead, though by a rather smaller margin. Over the 5 years to May 2008, the 400 companies in the FTSE4Good Index were about 15 per cent ahead of the general index.