The 30 Day MBA (38 page)

Authors: Colin Barrow

Current economic wisdom has it that a modest degree of inflation is healthy provided that everyone knows what it will be and can factor it into their decision making. That is why central banks have as one of their functions monitoring inflation rates and taking action to keep below a certain figure â in the UK this is 2 per cent. Three further aspects of inflation that need to be considered are:

Deflation

The opposite of inflation and occurs when the general level of prices is falling. This can occur after a major bubble collapses and will lead to people putting off purchasing decisions in the expectation of being able to buy later at even lower prices.

Japan experienced deflation when its boom in the 1980s turned to a long, wearying bust. Two decades of near zero interest rates have yet to yield anything resembling a dynamic economy. The Nikkei

Stock Market Index peaked at 38,916 on 29 December 1989 and at October

2010 was just 9,500â a measure of the country's economic morass.

Hyperinflation

This is unusually rapid self-feeding inflation; in extreme cases, this can lead to the collapse of a country's monetary system. This occurred in Germany in 1923, when prices rose 2,500 per cent in one month and in Zimbabwe in April 2008 when the annual inflation rate hit 165,000 per cent.

Stagflation

The combination of high economic stagnation with inflation, such as happened in industrialized countries during the 1970s, when OPEC raised oil prices.

Around half the money used to finance businesses is borrowed and private individuals use mortgages, hire purchase and credit cards to fund many of their purchases. Governments too have to use debt through the sale of bonds,

when taxes are insufficient to meet their spending plans. The âprice' of borrowed money is the interest paid. Governments can stimulate both business and consumer expenditure by lowering interest rates or choke off demand (see âMicro vs macroeconomics', above) by raising it. Interest rates are the favourite tool of central banks to control inflation as it can be used to bring supply and demand back into balance.

Interest rates also have a direct bearing on a country's exchange rate. If it is higher than that in other comparable economies it will tend to support the exchange rate at a higher rate, and if lower, the currency will tend to be weaker (see also âThe exchange rate'). There are, however, several different interest rates and governments do not directly control them all:

- Bank Base Rate: This is the interest set by governments, for example by the Bank of England's monetary committee, the US Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank. It is a reference point from which other interest rates are set, but is not the actual interest rate charged by clearing banks to their many and varied clients.

- Libor (London Inter-bank Offered Rate): This is the rate of interest at which banks borrow funds from each other, an essential activity to facilitate global trade and to settle contracts on futures and options exchanges. As such, it is the primary benchmark for short-term interest rates globally. The rate is set by a panel representing around 500 banks and depends on a number of factors, including local interest rates, expectations of future rate movements and the prevailing banking climate. Usually the Libor rate is lower than the rate set by central banks to allow banks a small margin. But if banks lose confidence in their peers' ability to repay then either they stop lending or they charge a premium over the Bank Base Rate. This was the case during the sub-prime crisis in 2007/08. Libor is both sensitive and complex. Rates are set in 10 currencies and for 15 different maturity dates, from an âovernight' rate maturing tomorrow, a âspot/next' rate that covers the period to the day after tomorrow, through weeks and months out as far as (but never further than) one year.

- Lending Rate: This is the rate at which banks will lend to businesses and private individuals. It can be anything from a fraction of a percent above either Bank Base Rate or Libor (whichever is the higher) for blue chip firms, a percent or two above for mortgages, and up to 15 per cent above for credit card loans; the higher the perceived risk the higher the rate.

Keeping the economy growing, holding inflation in check and attempting to both anticipate and mitigate the worst effects of downturns in the business

cycle are the primary economic goals of government. Dials showing the GDP growth rate and inflation are on every government's economy management dashboard. But these are not the only factors that affect an economy, nor is setting interest rates the only club in a central banker's locker.

Policy options

The UK's 1981 Budget, designed to remove several billion pounds from the economy when the UK was in the depths of recession, provoked an unprecedented letter from 364 economists published in

The Times

stating: âThere is no basis in economic theory or supporting evidence for the government's present policies.' In fact the UK economy recovered and eventually prospered. Even today, no politician, yet alone economist, can agree on whether the 364 economists were right or Lady Thatcher's then Chancellor of the Exchequer, Sir Geoffrey, now Lord, Howe. Although economists disagree on almost everything, they do accept that there are two broad categories of policy: fiscal and monetary.

Monetary policy

Monetarists, as the adherents of this school of thought are known, believe that as the economy runs on money, controlling the supply of the amount of money in circulation is the key to achieving growth without inflation. If the supply of money grows faster than the economy, inflation will rise as too much money will be chasing too few goods; too slow and growth is stifled. There are a number of difficulties in actually executing monetary policies:

- Measuring money: In the first place, agreement has to be reached on what exactly money is. There are at least five different and to some extent overlapping measurements, all attempting to measure the liquid assets at large in an economy. Designated with the prefix M, these measures range from M0, the narrowest definition which includes only the cash held in banks and in circulation, through to M5, the broadest measure which extends to a wide range of other short-term highly liquid financial assets held as a substitute for deposits. Not content with these five measures, some now have letter prefixes to subdivide further the types of liquid assets included. If you can imagine trying to drive a car with several speedometers you will get a feeling for the problem. In the world boom of 1972â73, for example, the UK's M3 and M4 grew at nearly 25 per cent per annum; M5 grew at over 20 per cent, yet M1 grew at only 10 per cent.

- Velocity of circulation: Money's use is as a medium of exchange; we swap it for goods and services, which in turn create the value in an economy that result ultimately in GDP. Over any interval of time, the money one person spends can be used later by the recipients of that money to purchase other goods and services, the suppliers of which

can then themselves spend the same cash again. The more times cash circulates each year the higher the velocity and hence the money supply available to fuel GDP. To measure money supply we need to know the velocity of circulation but it is notoriously difficult to do, is different for each of the Ms and can change over time.

Central bankers have three tools to help control the amount of money in circulation:

- Open market operations are where the central bank sells government securities to banks, leaving them with less cash to lend.

- Reserve requirements are the proportion of reserves a bank must keep in relation to the amount of money it can lend. Raising the level of reserves reduces banks' capacity to lend.

- Discount rate is the interest rate the central bank charges banks. Raising that rate reduces the money available to lend.

Fiscal policy

A government's approach to tax and spending is known as its fiscal policy. Cutting taxes and so giving consumers and businesses more money to spend can stimulate an economy. Alternatively, raising taxes can cool an economy down if it looks like overheating. Governments can themselves increase spending, both by using taxes and by borrowing money raised by issuing government securities. The latter approach is termed deficit spending and has been understood and used extensively since popularized by Maynard Keynes in the 1920s. He showed how governments could use this aspect of fiscal policy either to avert a recession or to reduce its effect on unemployment.

The spending multiplier effect

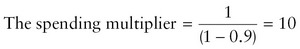

Keynesian economists deduced that government expenditure multiplies through the economy having a far greater ripple effect than the initial sum involved, making such activity more important than the sums themselves may sound. Let's suppose the government decides to embark on a major programme of school building, resulting in $/£/â¬100 million of salaries for construction workers. The impact of their salaries on the economy depends on their marginal propensity to consume (MPC) â in other words, how much of their salary they will save and how much they will spend. If we suppose that they will save 10 per cent of salary (the approximate 20-year average, though at the time of writing it was less than 6 per cent), then they will spend 90 per cent. That gives an MPC of 0.9, which is 90 per cent expressed as a decimal:

So the effect of £100 million of government spending on the wider economy is 10 à £100 million, or £1,000 million, because each 90 per cent of a worker's income is spent, which in turn becomes someone else's income of which they spend 90 per cent, and so on.

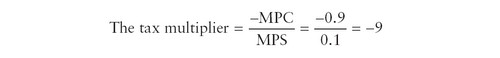

The tax multiplier

Tax reductions are another way in which governments can affect expenditure by giving or taking money away from consumers, and that too has a multiplier effect. This formula is almost identical to that for the spending multiplier. The only difference is the inclusion of the negative marginal propensity to consume (âMPC). The MPC is negative because an increase in taxes decreases income and hence the ability to consume. If we again assume that 90 per cent of income is spent and 10 per cent saved, we have a marginal propensity to consume of 0.9 and a marginal propensity to save of 0.1. This gives a tax multiplier of â9 (see below), which means that if taxes are raised by £100 million that will result in â9 à £100 million; in other words, £900 million will be taken out of consumption.

The converse is of course true; were taxes reduced by £100 million, consumption would rise by £900 million.

Using tools and policies to keep an economy growing and inflation low is certainly a government's primary goal; but they do have some other parallel and interrelated outcomes in mind. These are not so much secondary objectives, but like inflation are more the effect of mismanagement, bad timing or major events in a big economy with which much business is conducted. The most important of these concerns include the following.

Employment vs unemployment

Government's stated goal in this respect is to maintain the economy at full employment. That has the benefit of keeping most citizens happy, while contributing tax to the general good. However, if everyone is in a job the only way a new or growing business can recruit additional staff is to poach from other organizations, usually by offering higher wages. That in turn feeds into inflation, as wage prices, a major component of costs, are rising without there necessarily being an increase in output. Also, high employment can lead to the âjobs for life' attitude prevalent in Japan for so long that contributed to its market inefficiencies.

In practice, governments actually set their policies to achieve an acceptable level of unemployment. In the UK and United States that is around 5 per cent of the labour force, while in continental Europe between 9 and 10 per cent has become the norm. High unemployment reduces a country's overall GDP through having unproductive workers. If the unemployed also get state welfare, as is the case particularly in continental Europe and to a lesser extent the UK, it increases the cost for the country as a whole.