The 30 Day MBA (45 page)

Authors: Colin Barrow

Forecasting

Sales drive much of a business's activities; it determines cash flow, stock levels, production capacity and ultimately how profitable or otherwise a business will be, so, unsurprisingly, much effort goes into attempting to predict future sales. A sales forecast is not the same as a sales objective. An objective is what you want to achieve and will shape a strategy to do so. A forecast is the most likely future outcome given what has happened in the past and the momentum that provides for the business.

The components of any forecast are made up of three components and to get an accurate forecast you need to decompose the historic data to better understand the impact of each on the end result:

- Underlying trend: This is the general direction, up, flat or down, over the longer term, showing the rate of change.

- Cyclical factors: These are the short-term influences that regularly superimpose themselves on the trend. For example, in the summer months you would expect sales of certain products, swimwear, ice creams and suntan lotion, for example, to be higher than, say, in the winter. Ski equipment would probably follow a reverse pattern.

- Random movements: These are irregular, random spikes up, or down, caused by unusual and unexplained factors.

Using averages

The simplest forecasting method is to assume that the future will be more or less the same as the recent past. The two most common techniques that use this approach are:

- Moving average: This takes a series of data from the past, say the last six months' sales, adds them up, divides by the number of months and uses that figure as being the most likely forecast of what will happen in month 7. This method works well in a static, mature marketplace where change happens slowly, if at all.

- Weighted moving average: This method gives the most recent data more significance than the earlier data since it gives a better representation of current business conditions. So before adding up the series of data each figure is weighted by multiplying it by an increasingly higher factor as you get closer to the most recent data.

Exponential smoothing and advanced forecasting techniques

Exponential smoothing is a sophisticated averaging technique that gives exponentially decreasing weights as the data gets older and conversely more recent data is given relatively more weight in making the forecasting. Double and triple exponential smoothing can be used to help with different types of trend. More sophisticated still are Holt's and Brown's linear exponential smoothing and Box-Jenkins, named after two statisticians of those names, which applies autoregressive moving average models to find the best fit of a time series.

Fortunately, all an MBA needs to know is that these and other statistical forecasting methods exist. The choice of which is the best forecasting technique to use is usually down to trial and error. Various software programs will calculate the best-fitting forecast by applying each technique to the historic data you enter. Then wait and see what actually happens and use the technique that's forecast as closest to the actual outcome. Professor Hossein Arsham of the University of Baltimore (

http://home.ubalt.edu/ntsbarsh/Business-stat/otherapplets/ForecaSmo.htm#rmenu

) provides a useful tool that allows you to enter data and see how different forecasting techniques perform. Duke University's Fuqua School of Business, consistently ranked among the top 10 US business schools in every single functional area, provides this helpful link (

www.duke.edu/~rnau/411home.htm

) to all its lecture material on forecasting.

Causal relationships

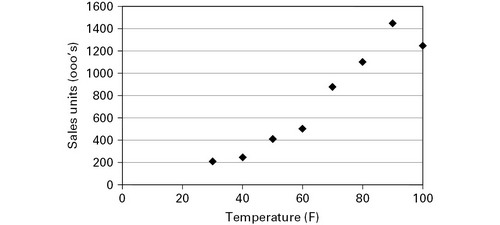

Often, when looking at data sets it will be apparent that there is a relationship between certain factors. Look at

Figure 11.3

. It is a chart showing the monthly sales of barbeques and the average temperature in the preceding month for the past eight months.

FIGURE 11.3

Â

Scatter diagram example

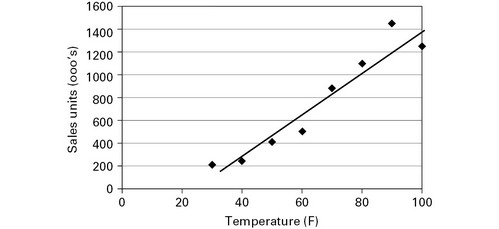

It's not too hard to see that there appears to be, as we might expect, a relationship between temperature and sales, in this case. By drawing the line that most accurately represents the slope, called the line of best fit, we can have a useful tool for estimating what sales might be next month, given the temperature that occurred this month (

Figure 11.4

).

FIGURE 11.4

Â

Scatter diagram â the line of best fit

The example used is a simple one and the relationship obvious and strong. In real life there is likely to be much more data and it will be harder to see if there is a relationship between the âindependent variable', in this case temperature, and the âdependent variable', sales volume. Fortunately, there is an algebraic formula known as âlinear regression' that will calculate the line of best fit for you.

There are then a couple of calculations needed to test if the relationship is strong (it can be strongly positive or even if strongly negative it will still be useful for predictive purposes) and significant. The tests are known as R-squared and the Students

t

-test, and all an MBA needs to know is that they exist and you can probably find the software to calculate them on your computer already. Otherwise you can use Web-Enabled Scientific Services & Applications (

www.wessa.net/slr.wasp

) software, which covers almost every type of statistical calculation. The software is free online and provided through a joint research project with K.U.Leuven Association, a network of 13 institutions of higher education in Flanders.

For help in understanding these statistical techniques, read

The Little Handbook of Statistical Practice

by Gerard E Dallal of Tufts, available free online (

http://gpvec.unl.edu/bcpms/files/Epi/mod3/Project%20Resources/LittleHandbookofStatisticalPracticeDallal.pdf

). At Princeton's website (

http://dss.princeton.edu/online_help/analysis/interpreting_regression.htm

) you can find a tutorial and lecture notes on the subject as taught to its Master of International Business students.

Qualitative research and analysis

Qualitative research is a well-entrenched academic tradition in sociology, history, geography and anthropology; it is widely used in the medical and political fields. It has made much less of a mark in business, perhaps because of its image as a softer, more ethereal discipline. That situation is changing with the growing realization that while quantitative research can reveal what issues are important and even where they lie, it is of rather less use in understanding why they have come about or what to do about them. Qualitative research comes into its own particularly when these are important factors:

- Complex issues: Quantitative methods are useful for separating out and measuring individual factors, say what percentage of customers are dissatisfied with a product or service and how many will defect. Qualitative methods can help get an understanding of the linkages between these factors and the competing tensions they arouse.

- Stakeholders' differences: Not everyone involved in an organization sees matters from the same perspective. Often the aggregation nature of quantitative methods makes it difficult to fully appreciate the position of less powerful stakeholders. Qualitative research gives individuals a voice in the analytical process.

- Significant recommendations: When the consequences of research are likely to result in recommendations with significant consequences, for example changing work patterns, shutting down a unit or altering pay and conditions, qualitative research allows attitudes and feelings towards potential courses of action to be explored, leading hopefully to a less contentious outcome.

Researchers used to quantitative analysis frequently dismiss qualitative research as âunscientific' and âanecdotal'. It certainly doesn't have to succumb to such criticism, as the array of tools used in qualitative research is large and the tools have a well-documented and rigorous methodology for their application.

Observation

The power of observation as a method of gathering data lies in the inconsistency between what people will say in an interview, or on a questionnaire, and what they actually do. It's not that people are necessarily lying, it's just that their capacity for self-deception is often high. Customers may feel foolish admitting they have difficulty finding their way around a shop and so would not record that fact. That doesn't mean that they don't have a problem and that a company would not gain valuable information from finding out about it.

So observations can give valuable insights into how things look from an outsider such as a customer, supplier or prospective employee. But such insights will only be representative of the time the researcher was observing and may not be indicative of the general level of service. They are often used to provide contextual information alongside some other research method.

Observations themselves generally come in one of two forms:

- Participating observation: This is where the observer takes part in at least some aspect of what is being assessed in order to get a better understanding of insider views and experiences. This, for example, could involve going through the whole procedure of making a purchase or using a service, rather than standing on the sidelines watching others. This is the methodology used in mystery shopping.

- Pure observation: Here the observer stays aloof from the situation under assessment so as not to influence it and so perhaps bias the findings.

The great difficulty in carrying out this type of research is being able to record observations accurately. Taking notes can be conspicuous and will almost certainly put those being observed on their guard.

Interviews

Talking and listening to people is the most basic and the most used method of conducting qualitative research. Qualitative interviews can take several forms and can be incorporated into triangulation methods (see below). These are the main interview types:

- Open-ended ad hoc conversations allowing interviewees to drive the discussion with minimum intervention by the interviewer; for example users of a product or service could be asked to give their feelings without being steered towards questions concerning satisfaction or dissatisfaction. This approach can throw up issues that have not been explored by the researcher.

- Open-ended interviews where the broad issues to be covered are stated, but the course of conversation is allowed to decide the order or ways in which questions are asked.

- Semi-structured interviews where the questions are largely planned in advance, with time left for issues that arise mainly as a result of the conversation itself.

- Qualitative questions built into structured surveys and questionnaires, where the main thrust is to gather quantitative data. For example, in an interview carried out to measure staff morale, questions such as âhow do you feel about the new pay scale?' could be interspersed with questions that gather quantitative data such as âdo you now feel: 10 per cent better off; the same; 10 per cent worse off?'.

- Cognitive interviews: These are used to test respondents' understanding of the meaning of questions or statements and are eventually to be used in questionnaires, user instructions and manuals, for example.

Qualitative interviews differ from surveys, for example in that they adhere less to a fixed set of questions but continually probe and cross-check information, building cumulatively on the knowledge gained from earlier answers. Nevertheless, interviewers at some point have to ask the questions that give them the specific data they need. Good interpersonal skills, sensitivity to the respondent, conducting the interviews at an appropriate time and place, using trained interviewers as well as having an appropriate sample are all vital to successful interviewing.

Focus groups

Focus groups are a form of multiple interview, with small groups of around 8 to 10 people selected with specific key attributes in mind: specific knowledge, experience or socioeconomic characteristics, for example. Participants are invited to attend informal discussion sessions of no more than two hours' duration on a particular topic, facilitated by someone knowledgeable about the issues involved, but tactful and firm enough to keep the group in order and on task. Often an incentive is offered for people to attend. The advantages of using a focus group over interviews include efficiency, as you can get 10 opinions in around twice the time it takes to conduct an interview; and by listening to other people's comments, often more ideas, opinions and experiences and insights can be gained. It is also easier to take notes of the discussion as this is expected and less threatening in a group situation. But, as with interviews, it relies on the views of a small sample and so is not truly representative of any body of opinion.