Stonehenge a New Understanding (28 page)

Read Stonehenge a New Understanding Online

Authors: Mike Parker Pearson

Tags: #Social Science, #Archaeology

Attitudes to human bones among the many Pagan groups in Britain are very diverse. There is even a group of Pagans for Archaeology, many of whom have no problem with the keeping of bones in museums. Perhaps it is like any cross-section of society, with moderates and an extremist fringe. Anyway, we were soon to meet some people who (I hope) represented the latter minority.

Before we started work on excavation at the Aubrey Hole, the manager of Stonehenge, Peter Carson, invited a small group of Pagans to perform a ceremony of their choice. The same had been done for Geoff and Tim’s dig. After years of conflict over the banning of solstice festivals at Stonehenge since 1985, English Heritage had changed its policy in the 1990s: Now, instead of confrontation, it seeks negotiation. My colleagues and I could see no objection to the peaceful public performance of any religious ritual that anyone cared to undertake (except that we had a tight schedule and needed to get to work); I certainly have no desire to dictate to others what they should or shouldn’t believe, and my own beliefs are irrelevant. My personal view is that Druids and other Pagans have a great deal in common with archaeologists—the members of both groups know a great deal about our ancient heritage; they see it as being of inestimable value and care very deeply about what happens to it.

About sixty people turned up in the field outside Stonehenge, wearing what I think was religious costume—a variety of robes and antlers—banging drums and shouting, to the alarm of both the diggers and the visiting public. Two small girls burst into tears and had to be calmed by their parents. Tolerance was apparently a one-sided affair: Julian Richards was publicly condemned with a Druidical curse. Finally, the proceedings calmed down and a Pagan blessing was provided next to the parking lot by some of the more moderate celebrants.

11

__________

By the early 1930s, mass tourism had reached Stonehenge. There was a pressing need for visitors to have somewhere to park their cars. In January 1935, in consequence, Robert Newall (Lieutenant Colonel Hawley’s assistant) and William Young (who had worked at Woodhenge for archaeologist Maud Cunnington in the 1920s) were digging in advance of the construction of this first parking lot just to the northwest of Stonehenge. They took the opportunity to re-open Aubrey Hole 7 and bury in it all the cremated human bones that had been found by Hawley at Stonehenge. They kept a written record of their work but didn’t record why they chose Aubrey Hole 7—though its large size and proximity to the road might have been the reason. Young recorded in his diary that they dumped four sandbags of bone in the re-opened hole; so that future archaeologists would know what these bones were—and in case Young’s diary did not survive—they also left an inscribed lead plaque in the pit on top of them.

Working out what the Aubrey Holes were originally used for is tricky. Before working at Stonehenge, Atkinson had dug a series of pit circles on the river terrace gravels at Dorchester-on-Thames in Oxfordshire, so he had some experience of this type of Neolithic feature.

1

After digging two Aubrey Holes in 1950, he decided that the Aubrey Holes “were never intended to hold any kind of upright, either the bluestones . . . or wooden posts.”

2

They were just a circle of pits. Later archaeologists tended not to agree with him. By the time our project started, the usual interpretation given in guidebooks and elsewhere was that the Aubrey

Holes had once held wooden posts. Josh Pollard, for example, could easily interpret the old excavation records and the beautiful sections drawn for Atkinson by Stuart Piggott to see that the compacted chalk rubble found in all the holes was best explained as packing around a central upright.

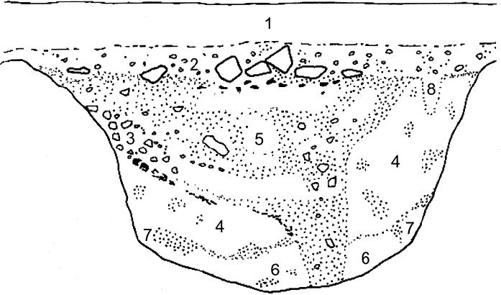

A section of Aubrey Hole 32, drawn by Stuart Piggott, showing the filled-in void where a bluestone once stood (5) and the chalk packing material for the stone (4, 6, 7) from which bones of a cremation burial were recovered (4). To the left (at 3), the side of the pit has been crushed and the packing layer displaced where the stone was removed.

Going back through Hawley’s notes and reports of his excavations in the 1920s, I discovered that he had made careful observations about how the Aubrey Holes had been used. He noted that the chalk bottoms of at least two of them had been compacted and crushed. Many more, Hawley wrote, had their edges “shorn away, or crushed down, on the side toward the standing stones of Stonehenge, this being apparently due to the insertion or withdrawal of a stone, probably the latter.” In 1921, he concluded that “there can be little doubt that they [the Aubrey Holes] once held small upright stones.”

3

For some reason, Hawley didn’t have the courage of his convictions and later changed his mind.

4

In his diary he wrote that Maud Cunnington and her husband had convinced him that the Aubrey Holes were postholes. Their excavation at Woodhenge between 1926 and 1928 had uncovered evidence that part of this Neolithic monument consisted of massive wooden posts, not just standing stones. These Woodhenge postholes were about the same diameter as the Aubrey Holes so superficially looked very similar.

In 2007, I began to wonder if Hawley had been right the first time. In all the discussion and mulling over what the Aubrey Holes could have

once held—timber, stone, or nothing at all—no one had thought to make a very careful comparison of the dimensions of these intriguing pits with those of known postholes or stoneholes. There are plenty of excavated examples to make such a comparison possible—from Stonehenge itself one can examine the records of excavated sarsen holes, the bluestone Q and R Holes, and other bluestone-holding holes. From our own experience at Woodhenge and Durrington Walls, and its avenue, we knew that stoneholes are much shallower than postholes of equivalent diameter. The stoneholes we had dug also had a thin layer of crushed chalk at their bases, which is something not found in even the largest of the postholes.

The results of a metrical comparison between Neolithic postholes and Neolithic stoneholes are very clear.

5

The Aubrey Holes are too narrow to be pits, and too shallow to be postholes. They are, on average, half a meter shallower than postholes of equivalent diameter. They are also narrower than either sarsen holes or, for example, the Neolithic pits found at Dorchester-on-Thames by Atkinson. The Aubrey Holes are, in fact, identical in width, depth, and shape to the bluestoneholes located elsewhere in Stonehenge.

One might wonder whether the Aubrey Holes held small, short posts in shallow sockets, thereby contrasting with the normally deep postholes at other Neolithic sites, such as Woodhenge and the Southern Circle. But that cannot be the case because such short posts would not have been heavy enough to cause the crushing and compaction that Hawley noted within the Aubrey Holes.

Returning to Piggott’s section drawings of the Aubrey Holes, I could see how the crushed chalk rubble that fills the holes had been deposited and then displaced. It seems that the chalk fill had initially been packed against the base of a stone in each hole and was then displaced on one side when the stone was pulled out. Looking at the drawings, it is evident that in Aubrey Hole 32, for example, not just the rubble but also the side of the pit itself was crushed by withdrawing a stone, just as Hawley had observed on other examples.

6

From the records and drawings alone, a very strong case can be made for the Aubrey Holes having held small upright stones—presumably the bluestones—and for these to have formed a stone circle right at the beginning of Stonehenge’s sequence.

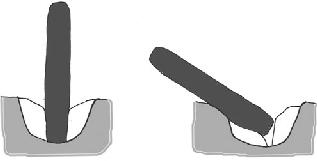

Removing a bluestone from an Aubrey Hole, showing how the shape of a pit is altered when a stone is removed.

I am puzzled as to why Atkinson said that the Aubrey Holes had held no uprights of either wood or stone. If a pit is dug and then filled in, an archaeologist can see the clear edges where the pit was cut into the soil. If a timber post is left to rot

in situ

, you see a parallel-sided “pipe” within the pit, where the timber has decayed. If an upright is pulled out of a pit, however, it changes the shape of the pit’s sides, because of the movement of soil caused by levering it out. These differences can be hard to spot for someone with little experience of digging postholes and stoneholes.

To work out what happened at Stonehenge, we needed to know more about the Aubrey Holes, to find out both what they were for and when they were dug. Everyone agrees that the construction sequence at Stonehenge begins with the ditch and bank. These were constructed at some point within 3000–2920 BC, on the basis of Bayesian-modeled radiocarbon dates. Some archaeologists reckoned that the Aubrey Holes belonged to this earliest phase, because they are set in a ring just inside the circles of the bank and ditch; others thought they must be part of a later phase.

To date the Aubrey Holes, we turned to Salisbury and South Wiltshire Museum again, which has responsibility for many of the prehistoric finds from Wessex. Given the amount of archaeological investigation that has been carried out at Stonehenge, and the huge amount of effort that has gone into unraveling the construction sequence, it is truly surprising that there is material still waiting to be dated. The curators in Salisbury take care of three cremation burials excavated by Atkinson and gave us permission to take samples for radiocarbon dating.

One of these cremation burials was found in Aubrey Hole 32, excavated during Atkinson’s very first Stonehenge season in 1950. Piggott’s impeccably drawn section shows that the bone fragments were found scattered within the layer of compacted chalk rubble packed into the bottom sides of the hole; these bones were therefore deposited in the initial fill of the hole, and not inserted later.

We sent a small sample of cremated bone off to the lab. Material for radiocarbon dating (C14 dating) has to go to one of a handful of specialist labs with accelerator mass spectrometers. The two labs that we use are in Glasgow and Oxford. Radiocarbon dating is a slow process that takes many months. On completion, the results are sent to the excavator by letter—until it arrives you don’t know the date of your sample. When our result finally came back, we learned that this Aubrey Hole cremation burial dates to 3030–2880 cal BC, the same period as the antler picks found at the bottom of the Stonehenge ditch, so we were confident that the Aubrey Holes did belong to Stonehenge’s initial phase of construction.

7

We also sent for radiocarbon dating two other cremations found by Atkinson, not from Aubrey Holes but from different layers within the ditch. These dated to around 2900 BC and around 2500–2300 BC. As well as carefully buried cremated bones, loose human bones were also being scattered at Stonehenge: Two fragments of unburned human skulls from the ditch date to 2800–2600 BC.

We now had some new dates to add to the existing chronology for Stonehenge’s construction and use. The 1995 book

Stonehenge in Its Landscape

by Ros Cleal and her team had finally provided the full and definitive account that Atkinson, Piggott, and Stone had envisaged, though only Piggott lived long enough to see it. Cleal’s team had examined all the existing radiocarbon dates, working out whether they were from secure contexts or not, and English Heritage had paid for a new suite of dates from antler picks and animal bones. Here was a solid framework for Stonehenge’s chronology, but there were still some problems to be ironed out. How did our new dates for the Aubrey Hole and for the other human bones fit into the chronology?

The new dates affected the chronology in two ways. Firstly, the orthodox view, that Stonehenge was used as a cemetery for just a short period of time around 2600 BC, was wrong. The new radiocarbon dates showed

that Stonehenge had started as a place of burial, since the Aubrey Hole cremation dates to the moment of Stonehenge’s construction and initial use. Secondly, the new date showed that the Aubrey Holes were definitely some of the first constructions at Stonehenge. If we were right that they once held bluestones, this had significant implications for the sequence of construction and the dates of the different stages of the monument. If Stonehenge had actually started as a bluestone circle shortly after 3000 BC, these stones must have arrived more than five hundred years earlier than anyone had previously reckoned.