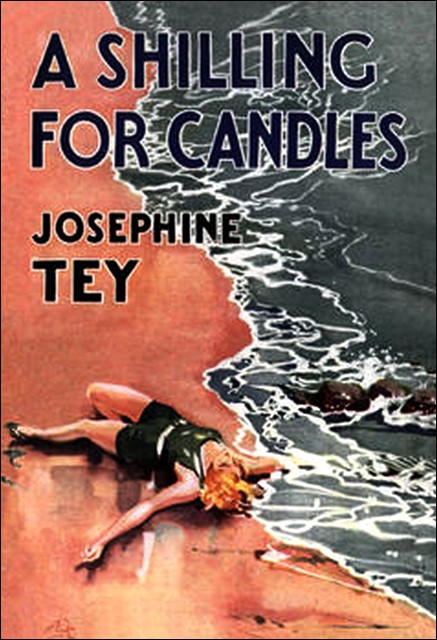

A Shilling for Candles

RGL e-Book Cover 2014

©

First US edition: The Macmillan Company, New York, 1951

This e-book edition: Roy Glashan’s Library, 2014

Produced by Colin Choat and Roy Glashan

“A Shilling for Candles,” Methuen & Co. Ltd., London, 1936

IT was a little after seven on a summer morning, and William

Potticary was taking his accustomed way over the short down grass of the

cliff-top. Beyond his elbow, two hundred feet below, lay the Channel, very

still and shining, like a milky opal. All around him hung the bright air,

empty as yet of larks. In all the sunlit world no sound except for the

screaming of some seagulls on the distant beach; no human activity except for

the small lonely figure of Potticary himself, square and dark and

uncompromising. A million dewdrops sparkling on the virgin grass suggested a

world new-come from its Creator’s hand. Not to Potticary, of course. What the

dew suggested to Potticary was that the ground fog of the early hours had not

begun to disperse until well after sunrise. His subconscious noted the fact

and tucked it away, while his conscious mind debated whether, having raised

an appetite for breakfast, he should turn at the Gap and go back to the

Coastguard Station, or whether, in view of the fineness of the morning, he

should walk into Westover for the morning paper, and so hear about the latest

murder two hours earlier than he would otherwise. Of course, what with

wireless, the edge was off the morning paper, as you might say. But it was an

objective. War or peace, a man had to have an objective. You couldn’t go into

Westover just to look at the front. And going back to breakfast with the

paper under your arm made you feel fine, somehow. Yes, perhaps he would walk

into the town.

The pace of his black, square-toed boots quickened slightly, their shining

surface winking in the sunlight. Proper service, these boots were. One might

have thought that Potticary, having spent his best years in brushing his

boots to order, would have asserted his individuality, or expressed his

personality, or otherwise shaken the dust of a meaningless discipline off his

feet by leaving the dust on his boots. But no, Potticary, poor fool, brushed

his boots for love of it. He probably had a slave mentality, but had never

read enough for it to worry him. As for expressing one’s personality, if you

described the symptoms to him he would, of course, recognize them. But not by

name; In the Service they call that “contrariness.”

A seagull flashed suddenly above the cliff-top, and dropped screaming from

sight to join its wheeling comrades below. A dreadful row these gulls were

making. Potticary moved over to the cliff edge to see what jetsam the tide,

now beginning to ebb, had left for them to quarrel over.

The white line of the gently creaming surf was broken by a patch of

verdigris green. A bit of cloth. Baize, or something. Funny it should stay so

bright a color after being in the water so—

Potticary’s blue eyes widened suddenly, his body becoming strangely still.

Then the square black boots began to run.

Thud, thud, thud,

on the

thick turf, like a heart beating. The Gap was two hundred yards away, but

Potticary’s time would not have disgraced a track performer. He clattered

down the rough steps hewn in the chalk of the Gap, gasping; indignation

welling through his excitement. That was what came of going into cold water

before breakfast! Lunacy, so help him. Spoiling other people’s breakfasts,

too. Schaefer’s best, except where ribs broken. Not likely to be ribs broken.

Perhaps only a faint after all. Assure the patient in a loud voice that he is

safe. Her arms and legs were as brown as the sand. That was why he had

thought the green thing a piece of cloth. Lunacy, so help him. Who wanted

cold water in the dawn unless they had to swim for it? He’d had to swim for

it in his time. In that Red Sea port. Taking in a landing party to help the

Arabs. Though why anyone wanted to help the lousy bastards—that was the

time to swim. When you had to. Orange juice and thin toast, too. No stamina.

Lunacy, so help him.

It was difficult going on the beach. The large white pebbles slid

maliciously under his feet, and the rare patches of sand, being about tide

level, were soft and yielding. But presently he was within the cloud of

gulls, enveloped by their beating wings and their wild crying.

There was no need for Schaefer’s, nor for any other method. He saw that at

a glance. The girl was past all help. And Potticary, who had picked bodies

unemotionally from the Red Sea surf, was strangely moved. It was all wrong

that someone so young should be lying there when all the world was waking up

to a brilliant day; when so much of life lay in front of her. A pretty girl,

too, she must have been. Her hair had a dyed look, but the rest of her was

all right.

A wave washed over her feet and sucked itself away, derisively, through

the scarlet-tipped toes. Potticary, although the tide in another minute would

be yards away, pulled the inanimate heap a little higher up the beach, beyond

reach of the sea’s impudence.

Then his mind turned to telephones. He looked around for some garment

which the girl might have left behind when she went in to swim. But there

seemed to be nothing. Perhaps she had left whatever she was wearing below

high-water level and the tide had taken it. Or perhaps it wasn’t here that

she had gone into the water. Anyhow, there was nothing now with which to

cover her body, and Potticary turned away and began his hurried plodding

along the beach again, and so back to the Coastguard Station and the nearest

telephone.

“Body on the beach,” he said to Bill Gunter as he took the receiver from

the hook and called the police.

Bill clicked his tongue against his front teeth, and jerked his head back.

A gesture which expressed with eloquence and economy the tiresomeness of

circumstances, the unreasonableness of human beings who get themselves

drowned, and his own satisfaction in expecting the worst of life and being

right. “If they want to commit suicide,” he said in his subterranean voice,

“why do they have to pick on us? Isn’t there the whole of the south

coast?”

“Not a suicide,” Potticary gasped in the intervals of hulloing.

Bill took no notice of him. “Just because the fare to the south coast is

more than to here! You’d think when a fellow was tired of life he’d stop

being mean about the fare and bump himself off in style. But no! They take

the cheapest ticket they can get and strew themselves over our doorstep!”

“Beachy Head get a lot,” gasped the fair-minded Potticary. “Not a suicide,

anyhow.”

“Course it’s a suicide. What do we have cliffs for? Bulwark of England?

No. Just as a convenience to suicides. That makes four this year. And

there’ll be more when they get their income tax demands.”

He paused, his ear caught by what Potticary was saying.

“—a girl. Well, a woman. In a bright green bathing dress.”

(Potticary belonged to a generation which did not know swimsuits.) “Just

south of the Gap. ‘Bout a hundred yards. No, no one there. I had to come away

to telephone. But I’m going back right away. Yes, I’ll meet you there. Oh,

hullo, Sergeant, is that you? Yes, not the best beginning of a day, but we’re

getting used to it. Oh, no, just a bathing fatality. Ambulance? Oh, yes, you

can bring it practically to the Gap. The track goes off the main Westover

road just past the third milestone, and finishes in those trees just inland

from the Gap. All right, I’ll be seeing you.”

“How can you tell it’s just a bathing fatality,” Bill said.

“She had a bathing dress on, didn’t you hear?”

“Nothing to hinder her putting on a bathing dress to throw herself into

the water. Make it look like accident.”

“You can’t throw yourself into the water this time of year. You land on

the beach. And there isn’t any doubt what you’ve done.”

“Might have walked into the water till she drowned,” said Bill, who was a

last-ditcher by nature.

“Ye’? Might have died of an overdose of bull’s-eyes,” said Potticary, who

approved of last-ditchery in Arabia but found it boring to live with.

THEY stood around the body in a solemn little group:

Potticary, Bill, the sergeant, a constable, and the two ambulance men. The

younger ambulance man was worried about his stomach, and the possibility of

its disgracing him, but the others had nothing but business in their

minds.

“Know her?” the sergeant asked.

“No,” said Potticary. “Never seen her before.”

None of them had seen her before.

“Can’t be from Westover. No one would come out from town with a perfectly

good beach at their doors. Must have come from inland somewhere.”

“Maybe she went into the water at Westover and was washed up here,” the

constable suggested.

“Not time for that,” Potticary objected. “She hadn’t been that long in the

water. Must have been drowned hereabouts.”

“Then how did she get here?” the sergeant asked.

“By car, of course,” Bill said.

“And where is the car now?”

“Where everyone leaves their car: where the track ends at the trees.”

“Yes?” said the sergeant. “Well, there’s no car there.”

The ambulance men agreed with him. They had come up that way with the

police—the ambulance was waiting there now—but there was no sign

of any other car.

“That’s funny,” Potticary said. “There’s nowhere near enough to be inside

walking distance. Not at this time in the morning.”

“Shouldn’t think she’d walk anyhow,” the older ambulance man observed.

“Expensive,” he added, as they seemed to question him.

They considered the body for a moment in silence. Yes, the ambulance man

was right; it was a body expensively cared for.

“And where are her clothes, anyhow?”

The sergeant was worried.

Potticary explained his theory about the clothes; that she had left them

below high-water mark and that they were now somewhere at sea.

“Yes, that’s possible,” said the sergeant.

“But how did she get here?”

“Funny she should be bathing alone, isn’t it?” ventured the young

ambulance man, trying out his stomach.

“Nothing’s funny, nowadays,” Bill rumbled. “It’s a wonder she wasn’t

playing jumping off the cliff with a glider. Swimming on an empty stomach,

all alone, is just too ordinary. The young fools make me tired.”

“Is that a bracelet around her ankle, or what?” the constable asked.

Yes, it was a bracelet. A chain of platinum links. Curious links, they

were. Each one shaped like a C.

“Well,” the sergeant straightened himself, “I suppose there’s nothing to

be done but to remove the body to the mortuary, and then find out who she is.

Judging by appearances that shouldn’t be difficult. Nothing ‘lost, stolen or

strayed’ about that one.”

“No,” agreed the ambulance man. “The butler is probably telephoning the

station now in great agitation.”