Stonehenge a New Understanding (31 page)

Read Stonehenge a New Understanding Online

Authors: Mike Parker Pearson

Tags: #Social Science, #Archaeology

Christie was already getting results soon after she began work. The complete cremation burial, missed by Hawley but found by us in 2008 in the side of Aubrey Hole 7, was that of an adult woman in her thirties who died in the period when Stonehenge was first built (3000–2920 BC) or in the century before. One of the cremations found by Atkinson in the Stonehenge ditch is also that of a woman, aged about twenty-five,

4

who died about five hundred years later, when the sarsen circle and trilithons were put up, or even a century after that. Although these two burials were

of women, Christie has so far found that all of the bones with identifiable sex traits from the mixed mass in the Aubrey Hole are those of men.

As for the age of the individuals, Hawley remarks in his records that he reckoned that only two of the cremations he found were those of children

5

and Christie’s findings reveal no more than four or five children of various ages. Jacqui had been very skeptical of Hawley’s ability to distinguish men, women, and children among the cremations—he had no training in anatomy—but he may not have been too far wrong in simply attributing clusters of very small bones to children as opposed to adults.

The picture that Christie is beginning to reveal is of a burial ground reserved predominantly for adult men. This is not a normal demographic picture. Before modern medicine, childhood mortality was very high, and most deaths in any population would have been those of children.

6

Thus if all members of a community were buried at Stonehenge, without discrimination, most of them should be children. Furthermore, half of the people should be women but, according to the identifiable sex traits among the adult bones, they are not there. In other words, there were strong biases at work in selecting people to be buried (as cremated remains) at Stonehenge.

Might the men whose remains were buried there have been sacrificial victims? We can look at the comparative examples of Neolithic and other prehistoric bog bodies from Scandinavia and northwest Europe; many of these show good evidence for having suffered a violent death, and archaeological opinion is very strongly in favor of their having been human sacrifices.

7

In contrast to the Stonehenge people, the bog bodies include a high proportion of women and children as well as men. Our overall knowledge of cremation across Britain during the Neolithic indicates that this was the standard burial practice for everybody, with some burials being provided occasionally with grave goods.

8

The most likely explanation is that the people buried at Stonehenge were drawn from an elite. They could have been rulers, born into the office, or chosen by their peers, or even ritual specialists who mediated between the living and the supernatural. The presence of a macehead and an incense burner in two of the burials gives weight to the idea that some sort of power, political and religious, was held by at least two of them.

The good preservation of the burned bone fragments has allowed Christie to find out about Neolithic illnesses and diseases. While none of the bones has produced evidence of violent trauma, several individuals had arthritis. This was not of the rheumatoid form (a disease that seems to have developed much later in human history) but was osteoarthritis. Christie has so far found it in the lower backs of some individuals, visible as patches of wear on the spine caused by degeneration of the cartilage between the vertebrae. One individual suffered from a soft-tissue tumor behind the knee. It was so large that it affected the growth of the tibia (the larger of the two lower leg bones) but was benign; it might well have caused a limp but not premature death.

The selection of samples from the Aubrey Hole cremations for dating is a mathematical puzzle. We know that there are fifty-nine burials (although some of these may contain more than one individual) in the form of fifty thousand fragments of human bone. How many bones need to be radiocarbon-dated to get a representative sample? We have to be sure that we don’t date the same individual twice. To avoid this, Christie and Jacqui must establish the minimum number of individuals (MNI) present and select one bone from each. This standard technique used to analyze all archaeological bone—human and animal—means finding out which anatomical part of the skeleton is most regularly represented; we will then radiocarbon-date each example of that.

Jacqui reckoned that the petrous bone (the outside of the ear cavity) is the one most easily identifiable, but we’d have to be careful not to destroy the actual cavity structure itself when sampling from the skull around it. So, if Christie finds twenty-five left petrous bones and twenty right petrous bones, our MNI will be twenty-five. If every one of these bones came from a different individual, there

might

be as many as forty-five individuals represented, but archaeologists have to ignore this number and work with what can be proved—in this example, the left-side bones would definitely come from twenty-five different people, so we would radiocarbon-date all the left-side petrous bones, and none of the right-side bones (which could be duplicates, belonging to the same people). The dates from these twenty-five individuals would give us a range for their deaths, and we would have to hope that this was a representative sample of the dates of death of each of the fifty-nine people.

We already have an inkling of how the burials should be distributed though time, so we know broadly what their numbers should look like from 3000 BC, the beginning of Stonehenge, to around 2400 BC, the latest date of Atkinson’s three cremations. This is because Hawley recorded not only where but at what depth he found each cremation burial within the Stonehenge ditch. Thanks to English Heritage’s dating of the ditch’s layers in 1994, we know the rate at which the ditch filled up over time. Our radiocarbon specialist, Pete Marshall, has been able to refine the chronology still further, by fine-tuning the statistical model. The cremation burial found by Hawley on the bottom of the ditch is likely to date to soon after its digging, around 2950 BC. Just two cremations were buried in the intermediate, secondary fills of the ditch; these ought to date to 2900–2600 BC. Fifteen were dug into the top of the ditch and can be expected to date to 2600–2300 BC.

A similar statistical exercise is also possible, but less certain, for the cremations from the fills of the Aubrey Holes. Up to eleven cremations (like the one found by Atkinson in Aubrey Hole 32) are probably primary burials from around 2950 BC. These deposits of cremated bone were later disturbed by the removal of small standing stones from these pits. Another twelve cremations are likely to have been inserted after the stones had been withdrawn and the pits filled in, perhaps around 2600–2300 BC. Thirteen of the cremations found by Hawley had been put into isolated pits that are impossible to date within the Stonehenge sequence, so no estimates of their dates can be made.

We also have to bear in mind the likely number of people buried at Stonehenge. Extrapolating from the number of known burials, Mike Pitts estimated in 2000 that it could be as many as 240. Although previous excavators have investigated about 50 percent of the area of Stonehenge, Mike reasoned that many undiscovered burials may lie under the outer bank and even outside the ditch. These are areas that have never been excavated, so there is no existing sample of burials to work with. My guess for the total number is slightly lower than Mike’s, at around 150.

The Stonehenge stratigraphy shows that very few people were buried there at the beginning of the sequence of construction, and lots were buried there toward the end of the monument’s use as a cemetery, about

five hundred years later. The overall pattern of this stratigraphic dating of the cremations suggests that only a minority of the Stonehenge dead (around ten out of 150) were buried at the beginning, with the numbers growing exponentially to around ninety cremation burials in the centuries around 2500–2300 BC.

Andrew Chamberlain, an expert in human osteology and ancient demography, estimates that this pattern of burials at Stonehenge could be created by a small kin group burying their dead over a five hundred-year period. The cemetery starts with a small number of founder graves. As the living offspring increase in number over about twenty generations, what started as a small family becomes a large number of families, or a lineage, descended from common ancestors. This may sound like a lot of people but, at a uniform rate of mortality, the number of burials at Stonehenge would derive from only one death every three or four years.

This gives us a model for what to expect from the results of the radiocarbon dating: We should find very few early cremations and a lot of later ones. If that is not the pattern, then there has to be something we have not accounted for—the unstratified burials may all belong to the early period of use, for example, or there may have been more primary burials in the Aubrey Holes than Hawley recognized.

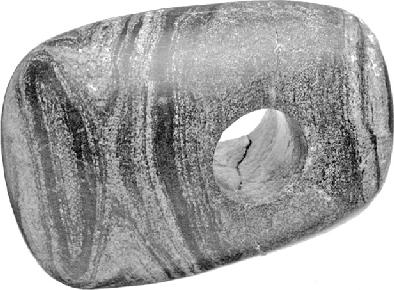

If Andrew is right about Stonehenge being a place of burial for a lineage, who were these people whose burial place was so illustrious? They were provided with no grave goods, except in one or two special cases. Hawley found one burial with a stone macehead, near the south entrance. Maceheads are ground and polished stones, drilled through the center for mounting on top of a wooden handle or staff.

9

The British Isles’ most beautiful example of a Neolithic macehead is an ornately carved specimen from the eastern chamber of the great tomb at Knowth in Ireland.

10

Another dates to about 1900 BC, probably some five hundred years later than the Stonehenge example, and was found just half a mile away from Stonehenge, in the richest prehistoric burial known from Britain. It came from Bush Barrow, a burial mound that lies on the skyline to the south of Stonehenge, and was excavated by Colt Hoare in 1808.

11

For many years, until Stonehenge’s re-dating in 1995, archaeologists wondered if the man buried in Bush Barrow had been responsible for the building of Stonehenge, since his grave goods were so rich and rare.

12

As well as a gold

lozenge-shaped ornament, a gold buckle, and bronze daggers with gold handles, he was provided with a macehead that had once been mounted on a staff decorated with chevron-shaped rings of bone.

The polished stone macehead found with one of the cremation burials at Stonehenge by William Hawley. It would have been attached to a wooden handle through the shaft-hole.

Maces could have been used as stone clubs, but there are good reasons for thinking that their role was primarily ceremonial. Even today in Britain, we recognize the mace as a symbol of power. The British parliament, local councils, and the Lord Mayor of London all have maces to proclaim institutional authority. Perhaps the Stonehenge mace had a similar purpose.

There is another peculiar grave good from among the Stonehenge cremations. This is a ceramic “incense burner”

13

—a small circular disc with concave surfaces on top and bottom. Holes on the sides show where it was suspended by string, and whatever substance was burned in it has left a sooty stain. Such items are known from all around the world as the paraphernalia of shamans and other ritual specialists. Ramilisonina and I have excavated such items, in use until a hundred years ago, that were

once used by Malagasy medicine men and diviners.

14

The Stonehenge “incense burner” is almost unique—only one other is known from the British Neolithic. Perhaps it tells us that some of the people buried at Stonehenge were ritual specialists as well as political leaders.

We might be tempted to ask why most of the burials had no grave goods—does this mean that these were not important people? But putting grave goods in the burial of an important individual is far from universal, across cultures and across time. Anthropological studies of traditional societies around the world have found that only in 5 percent to 40 percent of cases was social status signified by grave goods.

15

A lack of grave goods in a prehistoric burial is not an indication of lack of status; it all depends what the cultural traditions meant. On balance, given the small number of burials and their extraordinary location in this dramatic monument, it seems most likely that the people buried at Stonehenge were the elite of their day—rulers and shamans, perhaps forming a succession of powerful dynasties.

At the same time as Christie Cox Willis began to examine the cremated remains from the Stonehenge Aubrey Hole, I was coordinating a team exploring the lives of the people buried in the period afterward, from 2400 to 1800 BC. This project was not focused on the Stonehenge area but covered the whole of Britain.

16

Many of the skeletons from this period of the Copper Age and the Early Bronze Age were found with the distinctive form of pottery known as Beakers.

17

Ever since the nineteenth century, archaeologists have thought that the Beaker people were probably immigrants to Britain. Anatomists measured their skulls, pronouncing them to be round-headed (brachycephalic) in contrast to the long-headed (dolichocephalic) skulls from the Early Neolithic long barrows and, therefore, according to some, members of a different race.

18

Archaeologists saw these immigrants as the bringers of knowledge: It was in the Beaker period that metallurgy, horse-riding and brewing all first occur in Britain, spreading from the Continent.

19

The well-appointed Beaker burials often include not only the characteristic pottery but also archery equipment in the form of barbed-and-tanged arrowheads, and stone wrist-guards.