Stonehenge a New Understanding (29 page)

Read Stonehenge a New Understanding Online

Authors: Mike Parker Pearson

Tags: #Social Science, #Archaeology

12

__________

The dig to retrieve the 1935 deposit of cremated bones from Aubrey Hole 7 began, and all except a small handful of Druids went away. Now we could start trying to find out who those people buried at Stonehenge were. Hawley had stripped the entire area around Aubrey Hole 7 and its neighbors, and Newall and Young had dug it out for a second time, so we didn’t expect to find very much in the hole other than the reburied bones.

This Aubrey Hole is one of the largest and it was one of the most prolific in finds. Hawley recovered fifty-five sarsen hammerstones from this one hole, together with more than eighty bluestone and sarsen chips, and an ax-shaped bluestone. The bones of a disturbed cremation (of what he thought was a young adult) were scattered from top to bottom through the layers filling the southeast side of the pit. On the bottom of the pit, among chalk rubble, he found a small deposit of wood ash. Apart from three shards of Roman and Bronze Age pottery, and a single worked flint, Hawley did not bother to collect the smaller finds. In 1935 Newall and Young found an unfinished oblique arrowhead in his backfill. This was just the tip of the iceberg in terms of what he either missed or deliberately left behind: We found more than thirty worked flints, more chippings of sarsen and bluestone, and more shards of Roman and prehistoric pottery.

In the thirty-two Aubrey Holes that he excavated, Hawley found thirty cremations, more than four hundred hammerstones, and more than a thousand chips of bluestone and sarsen. Just like in the Q and R Holes, there was not a single antler pick. He noticed that most of the cremation

burials had been disturbed by the removal of what he reckoned were standing stones, but he also recorded that one or two cremations had been inserted after stone removal, because they remained intact and had not been crushed or otherwise disturbed. Cremation burials had also been placed around the edges of some of the holes.

Why all the hammerstones, stone chippings, and cremations? Atkinson believed the Aubrey Holes were neither structural nor sepulchral in their primary purpose. He thought that the cremations were introduced to the holes during their refilling, in the same way that ritual libations were made in pits as entrances to the underworld in Classical Greece. Yet Hawley was very clear that most of the burials had been included in the initial filling of the pits, and then disturbed later.

Hammerstones are fist-sized cobbles that have been used for pounding the surfaces of the sarsens. They are often used subsequently as packing for standing stones—Gowland found twenty-two of them slipped into the south side of the great trilithon upright to help fix it in place. Perhaps they were used for a similar purpose in the Aubrey Holes, or perhaps they were introduced after the stones were pulled out, to fill in the consequent depressions.

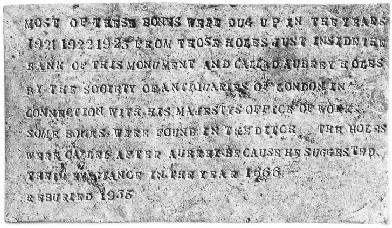

At the bottom of the loose soil tipped back in by Newall and Young in January 1935, we found the lead plaque that they had left there for us, the archaeologists of the future. It reads:

MOST OF THESE BONES WERE DUG UP IN THE YEARS 1921 1922 1923 FROM THOSE HOLES JUST INSIDE THE BANK OF THIS MONUMENT AND CALLED AUBREY HOLES BY THE SOCIETY OF ANTIQUARIES OF LONDON IN CONNECTION WITH HIS MAJESTYS OFFICE OF WORKS SOME BONES WERE FOUND IN THE DITCH THE HOLES WERE CALLED AFTER AUBREY BECAUSE HE SUGGESTED THEIR EXISTANCE IN THE YEAR 1666 REBURIED 1935

We were all a bit disappointed with this truly prosaic inscription—we’d secretly wished for something more archaeologically informative, or even more poetic. And it has a spelling mistake.

Once we’d carefully lifted the plaque, we could see a mass of cremated bones beneath. Scraping away the last of the loose soil on top of them, it was obvious that they had been dumped in a single heap. Young had written in his diary of their having been laid in four separate sandbags but there was no sign of any such division. It looked more likely that the bones had been poured into the hole, perhaps simply to keep the sandbags for re-use.

All of us had hoped that these archaeologists of the 1920s and 1930s had understood the value of context—and might therefore have appreciated the need to keep the bones from each burial separate. In the months before starting work, we’d been hoping that the bones from each burial had been kept separate in tins, paper bags, cloth wrappings—anything that could allow us to distinguish between the separate burials. We’d even fantasized that Newall and Young might have written indelible labels detailing from which context—or at least which Aubrey Hole—each burial had originally come.

Jacqui McKinley (top) and Julian Richards (right) excavating the undifferentiated mass of prehistoric cremated bones deposited in Aubrey Hole 7 in 1935.

The lead plaque left on top of the cremated bones in Aubrey Hole 7 by Robert Newall and William Young.

Instead, everything was mixed together. It was possible that the whole lot had not been utterly shaken up before being put in the ground, and that the bones from one burial might be packed next to the bones from another. If we took them out of the ground using a very precise three-dimensional grid of five centimeter blocks, it was just possible that specialist laboratory analysis could determine which bones belonged to which burials. The gloom induced by this archaeological carelessness was lifted by the optimism of Jacqui McKinley. She is the osteoarchaeologist (human bone specialist) for Wessex Archaeology, and has probably analyzed more cremation burials than anyone else in the world.

1

Not only were there far more bones than we had anticipated, but she was very pleased to see that they were generally large pieces in good condition.

When a body is cremated on a pyre, the fat and flesh burn away over a period of four to eight hours (depending on fuel and the tending of the fire) so that only the bones remain. These become calcined, turning blue and white, shrinking, warping, cracking, and splintering. Once the fire cools, they can be gathered off the pyre surface, which has become a mass of charcoal, ash, and calcined bones. Colin Richards has seen the whole process on an open-air pyre at a cremation ceremony on the Indonesian island of Bali. Many years ago, when I was doing some

research on modern British funerary practices, I spent some time with the staff at a British crematorium, peering through the furnace spy-hole to watch the flaming, bubbling fat and flesh burning off to leave a glowing red skeleton. The crematorium operator then takes a long iron tool and pokes the bones so that they fall in chunks down a chute, to be collected in a metal container. After they’ve cooled, the burned bone fragments are put into a “cremulator” (a machine that looks rather like a clothes-drier) to be reduced to tiny dust-sized particles.

Of course, the cremulator is a twentieth-century invention and prehistoric cremated bones never received this kind of final treatment. That said, archaeologists sometimes find that the bones from a cremation have broken into very small pieces and have been heavily weathered and eroded. Jacqui has also found that the average archaeological cremation weighs less than two pounds, whereas the weight of an adult’s burned bones should be around five pounds. Most prehistoric cremation burials have lost some of the bones along the way—partly, she thinks, because retrieval from the pyre would not have been particularly efficient, and partly because bones could well have been divided up so that not all were buried. For example, the three cremation burials excavated by Atkinson from Stonehenge vary in weight from 77 grams to 150 grams to 1,546 grams, with only the last one likely to comprise most of the recoverable bone.

With the last of the cremated bones removed from the bottom of Aubrey Hole 7, we troweled around the edges of the pit to find out whether there were other features—postholes and stakeholes—in its vicinity. There was a small stakehole on its west side and, to our surprise, a completely unexpected cremation burial close to the western edge of the hole. We’d seen the dark spread of its surface as soon as we had taken off the turf but had immediately assumed that it was something already investigated—two previous groups of very competent archaeologists had already dug here, after all.

It seems strange that William Hawley, as well as Newall and Young, missed this cremation burial. Capped by a small sarsen chipping, this was a small collection of cremated bones placed in a neat little hole cut just 10 centimeters into the chalk. The tidy, circular distribution of the bones indicated that they had been placed there within an organic container, most likely a leather bag, but possibly a birch-bark box or some other

form of circular wooden container. Hawley had indeed noted other burials as having been deposited in what he, too, thought had been leather bags. Having disturbed this unexpected cremation burial, we couldn’t leave it in the ground, so its fragile fragments were lifted and taken back to the laboratory with the mass of bones from Hawley’s excavations. This burial has produced a radiocarbon date of 3330–2910 BC, indicating that it was buried next to Aubrey Hole 7 right at the beginning of Stonehenge’s construction.

To Mike, Julian, and me it seemed extraordinary that this find had been overlooked. How many more such cremation deposits had Hawley failed to find within Stonehenge? Perhaps we should revise our estimates for the number of people buried at Stonehenge, since Hawley’s work had perhaps not been as thorough as everyone thought. Might the stakehole next to the burial have held a grave marker? How many more stakeholes had Hawley missed? He recorded only postholes, and perhaps his ability to recognize these ephemeral features across the ground surface of Stonehenge was not great. Maybe it’s no wonder that it’s difficult for archaeologists today to make sense of the arrangements of postholes recorded by Hawley: He may well have missed a lot of them.

The first cremated bones to be visible after our team lifted the lead plaque.

We could see that Hawley had failed to thoroughly clean out Aubrey Hole 7: He’d left a thin spread of chalk rubble undisturbed in the bottom. Here was a fortuitous opportunity to see if any evidence remained to show us at first-hand what had once stood, or had been put, in this hole. The chalk rubble was solid, so hard that I had to remove it with a hand pick; someone in prehistory had worked hard to ram and pack this chalk as firmly as possible. There was one spot without rubble, about 40 centimeters across, where a thin layer of chalk on the bottom of the pit had been crushed. We called Josh over to confirm what those of us who had previously dug stoneholes suspected. The majority of us agreed that we knew exactly what this was—the crushing of a chalk pit base by the weight of a standing stone.

q

It seems very likely that Stonehenge was a stone circle from its very beginning. From the sizes of the Aubrey Holes, it is evident that the stones they once held were small and narrow. This rules out the sarsens, so we’re confident that Stonehenge most likely started as a circle of fifty-six bluestones. Judging by the number of known empty stoneholes in the bluestone circle and Q and R Holes, from Atkinson onward archaeologists have estimated that around eighty bluestones were once here, employed in these later constructions.

2

If the first installation of bluestones was a circle of fifty-six in the Aubrey Holes, by the time the bluestone circle and bluestone oval were erected in the period 2280–2030 BC, another twenty-four or so bluestones had to be added to Stonehenge to reach a total of eighty. Many of these have been destroyed and removed; today just forty-three bluestones remain at the site.