Smuggler Nation (36 page)

Authors: Peter Andreas

Tags: #Social Science, #Criminology, #History, #United States, #20th Century

An Old American Tradition

Our story begins with a brief historical detour back to the colonial era. Illegally moving and settling, it turns out, is an old American tradition, even if it was not called “illegal immigration.” Consider, for instance, colonial defiance of the British Proclamation of 1763, which imposed a frontier line between the colonies and Indian territories west of the Appalachian Mountains. King George III prohibited colonists from moving across the line and settling, and he deployed thousands of troops to the western colonial frontier to enforce the law. The British feared loss of control over their subjects, and they also wished to avoid conflicts between colonists and Indians. But the colonists simply ignored the proclamation and illegally moved into what became Kentucky and Tennessee. Tensions between the colonists and British authorities over freedom of movement intensified until the outbreak of the American Revolution. And after Independence, these Anglo-American tensions persisted, but now over the illegal emigration of skilled British artisans. As we saw in

Chapter 6

, thousands of ambitious artisans managed to smuggle themselves out of the country in violation of strict British emigration laws, helping to jump-start the American industrial revolution.

Meanwhile, independence from Britain opened up enormous opportunities for illegal westward movement by settlers in defiance of central government authorities.

2

With the adoption by Congress of the Land Ordinances of 1784 and 1785, the national government planned to survey and then sell off territory west of the original states. The Northwest Ordinance, passed in August 1789, created the Northwest Territory, a geographic area east of the Mississippi River and below the Great Lakes. These land ordinances, designed by Congress to raise revenue, deter squatters, and promote orderly westward migration and settlement, were quickly undermined by a flood of unlawful settlers unwilling or

unable to pay for the public land. Squatters also moved onto Indian lands in violation of federal treaty obligations, often leading to bloodshed. The debates over the Northwest Ordinance included public denouncements of illegal squatters. William Butler of New York, for instance, complained, “I Presume Council has been made acquainted with the villainy of People of this Country, that are flocking from all Quarters, settling & taking up not only the United States lands but also this State’s, many Hundreds have crossed the Rivers, & are dayly going many with their family’s, the Wisdom of the Council I hope will Provide against so gross and growing an evil.”

3

In 1785 Congress empowered the secretary of war to crack down on illegal settlers, and the laws grew harsher as the problem persisted. The Intrusion Act of 1807 criminalized illegal settlement and authorized fines and imprisonment for lawbreakers. These measures were largely ineffective from the start. Testimony delivered to Congress in 1789 noted that the army “burnt the cabins, broke down the fences, and tore up the potatoe patches [of the squatters]; but three hours after the troops were gone, these people returned again, repaired the damage, and are now settled upon the land in open defiance of the union.”

4

Some states, such as Vermont and Maine, actually won statehood after being settled by illegal squatters who refused to buy the land from the legally recognized owners and violently resisted government eviction efforts. Even President Washington found it maddeningly difficult to remove illegal settlers from his western lands and bitterly complained about it.

5

The pattern of illegal settlement and intense (sometimes even violent) resistance to central government authority repeated itself for decades as migration accelerated and the frontier pushed westward.

6

According to one estimate, by 1828 two-thirds of Illinois residents were illegal squatters on federal land.

7

The westward demographic movement included European immigrants who entered the country legally but then settled illegally. Failing to deter and remove illegal settlers, Congress passed “preemption” acts, first in 1830 and again in 1841. These were essentially pardons for illegal settlement, providing legitimate land deeds at heavily discounted prices. The law, in other words, eventually adjusted and conformed to the realities of the situation, legalizing previously criminalized behavior.

8

Of course, even though illegal settlers defied the authorities and undermined the rule of law, in the end they were an essential part of westward expansion, very much serving the federal government’s objective of populating the West and extending the nation’s geographic reach. This included the illegal influx of American settlers into what is now the state of Texas despite Mexico’s decree of April 1830 prohibiting further immigration from the United States. Texas border officials paid little attention to such orders from a faraway central government. By 1836, the immigrant population greatly outnumbered Tejanos.

9

The Mexican government even deployed garrisons to try to control the influx, but the Americans continued to illegally move across the border. In this regard, the famous battle at the Alamo can be viewed as a militarized attempt to stop illegal American immigration—though that is not what “remember the Alamo” is meant to remind us of.

Last but not least, the smuggling of hundreds of thousands of African slaves into the country after the importation of slave labor was banned—first by states and then by the federal government—certainly qualifies as the most brutal form of forced illegal migration in the nation’s history. The federal government’s erratic and often halfhearted measures to restrict the illegal importation of slaves can be viewed as a form of immigration control. Moreover, as formally codified in the nation’s fugitive slave laws, escaped slaves residing in the North were essentially illegal immigrants. They were asylum seekers denied the legal protection of asylum, and therefore lived in constant fear of being deported back to the South. And even in the midst of the Civil War, fleeing slaves crossing Union lines were labeled “contrabands”; they remained in a legal limbo until the repeal of the fugitive slave laws and abolition of slavery.

Closing the Front Door

The federal government did not get into the business of controlling immigration in a serious and sustained way until the efforts to prohibit Chinese immigration in the 1870s and 1880s, marking the beginning of Washington’s long and tumultuous history of trying to keep out “undesirables.” Before then, regulating immigration was mostly left to the states to sort out.

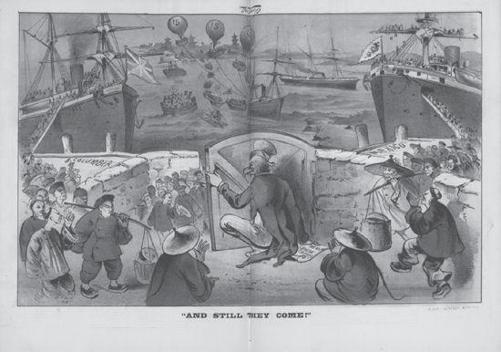

Figure 12.1 “And Still They Come.” Political cartoon depicts Uncle Sam trying to manage the influx of Chinese migrants through the front door while many sneak in via the back doors of Mexico and Canada.

The Wasp

, August–December 1880 (Bancroft Library, University of California).

Starting in the 1850s, tens of thousands of Chinese laborers (many of whom left China in violation of their country’s emigration laws

10

) were welcomed in the American west as a source of cheap labor, especially to build the transcontinental railroad. But they were never welcomed as people. From the start, Chinese could not become citizens. So it is little surprise that once the demand for Chinese labor dried up, an anti-Chinese backlash quickly followed. And it is also no surprise that the backlash was most intense in California, home to most of the country’s Chinese population.

11

By 1870, Chinese composed some 10 percent of the state’s population and about one-fourth of its workforce.

As political pressure to “do something” about the “yellow peril” intensified, Congress first passed the Page Act of 1875 (with enforcement mostly aimed at keeping out Chinese prostitutes), followed by the far more sweeping Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

12

These exclusions were renewed, revised, strengthened, and extended to other Asian groups in

subsequent years (and were not repealed until 1943). The front door was being closed and the welcome mat pulled up.

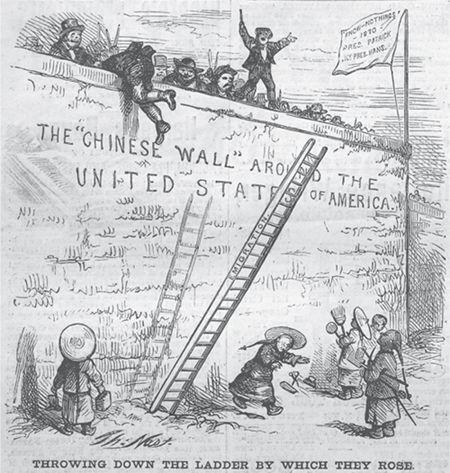

Figure 12.2 “Throwing down the ladder by which they rose.” Political cartoon of “The ‘Chinese Wall’ Around the United States of America.”

Harper’s Weekly

, July 23, 1870 (John Hay Library, Brown University).

But the door was not entirely shut. The law barred the entry of Chinese laborers but not Chinese in other categories: merchants, teachers, students, diplomats, and travelers. Also, Chinese who were legal U.S. residents before the exclusion law took effect could leave the country and return (though this right was later revoked). These exceptions to the exclusion laws created all sorts of opportunities for illegal entry through deception, as is evident in the many creative and sophisticated schemes used to impersonate being in a legally admissible category. Identification documents were sold and resold, borrowed and bartered, forged and doctored.

13

Laborers would pretend to be merchants, Chinese lawfully in the United States would return from trips to China with make-believe

children (“paper sons”

14

), and newly arriving Chinese would claim to have been born in San Francisco; all this was made much easier after birth records were destroyed by the earthquake-generated fire of 1906. One Seattle immigration agent explained the difficulty of sorting out legitimate from illegitimate arrivals: “There is not much way of checking on the Chinese when they get here. A number will have papers, a number will not have papers, and when asked why, they say they were born in San Francisco. Cannot show birth, for fire destroyed all.”

15

Former immigration inspector Clifford Perkins recollects, “At one time it was estimated that if all of those who claimed to have been born in San Francisco had actually been born there, each Chinese woman then in the United States would have had to produce something like 150 children.”

16

Steamship companies connecting China to San Francisco (notably the Pacific Mail Steamship Company, which dominated much of the shipping between Hong Kong and the United States) were well aware that many of their passengers were seeking unlawful entry.

17

Grueling interrogations of Chinese arriving by steamship at the San Francisco port could last days, weeks, or even months. An arrival and detention facility was opened on Angel Island in San Francisco Bay in 1910, where friends and relatives would smuggle in instructions—even inside peanut shells, banana peels, and care packages—to detainees on how to answer questions and fool the interrogators. Immigration guards could also sometimes be bought off to facilitate the smuggling of coaching notes to detainees.

18

The exclusion law included heavy penalties for violators. Fraudulent use of identification documents brought a fine of $1,000 and a maximum five-year prison term; aiding the entry of “any Chinese person not lawfully entitled to enter the United States” was subject to a fine and a maximum twelve-month prison term.

19

Over time, efforts to distinguish between lawful and unlawful entrants stimulated the development of a racially based national immigration control system increasingly reliant on standardized personal identification documents, photographs, visas, and so on.

20

These document requirements, pioneered by the Chinese exclusion laws, required creating entirely new federal administrative capacities, including document checks by U.S. consular officials in China.

21

Immigration law

evasion and law enforcement thus grew up together in the last decades of the nineteenth century and early decades of the twentieth century, in a political climate otherwise hostile to central government expansion.

22

And the elaborate immigration control system of documentation and registration first developed to keep out unauthorized Chinese could then be applied more widely.

23