Smuggler Nation (31 page)

Authors: Peter Andreas

Tags: #Social Science, #Criminology, #History, #United States, #20th Century

The Protectors of Protectionism

The years between the Civil War and the Great Depression have been called the “golden era of American protectionism.”

2

Between 1871 and 1913, the average tariff on dutiable imports was never less than 38 percent.

3

Although America was born espousing free trade and condemning British mercantilist restrictions, the country now embraced protectionism. And Britain, ironically, had become the world’s leading proponent

of free trade. Indeed, in the heated debates over protectionism, free-trade advocates were disparagingly labeled “English free traders.”

4

Epitomizing this remarkable metamorphosis was Rhode Island, which went from being one of the most trade-dependent and pro-free-trade colonies to an industrial manufacturing center nurtured by protectionist policies. Its jewelry makers, for instance, were protected by an 87 percent tariff. By 1907, Rhode Island was described in the

American Magazine

as a “tariff made” state—“high protection’s most perfect work”—with three-fourths of its population tied to factory jobs.

5

Thousands of customhouse workers—appraisers, collectors, inspectors, surveyors, gaugers, and weighers—served as the protectors of protectionism. They also enforced import bans on an increasingly long list of items, but their main job was revenue collection.

6

They sifted through luggage, inspected and weighed cargo, checked papers and documents, collected duties and imposed fines, and made seizures and arrests. Customs was the second largest federal employer after the postal service, with a workforce of more than thirteen hundred in New York alone by 1877.

7

Between July 1869 and July 1874, customs agents at the New York port seized more than thirty-six hundred shipments, secured sixty-eight smuggling-connected indictments, and collected more than $4 million in fines. Penalties were stiff. A complicit sea captain could face fifteen years in prison, a $5,000 fine, and loss of vessel; penalties for others could include up to a two-year prison term, a $10,000 fine, court costs, and payment of duties double the value of the smuggled item.

8

Like their British colonial predecessors, customs officials were often viewed as abusive, heavy-handed, and corrupt. Far from deferring to the “invisible hand” of the market, the customhouse was the most “visible hand” of the state.

9

Indeed, customs was the most striking exception to an otherwise anemic central state. Customs was the main generator of revenue for government coffers but was also used to line pockets and bankroll patronage politics. Unlike a century earlier, though, the abuses, graft, and corruption within customs generated pressures for reform rather than revolution.

10

In the years before Congress finally pushed to reform customs in the 1870s, revenue enforcement was remarkably profitable: under the “moiety system,” which dated back to the eighteenth century, agents and their informants could be awarded a substantial cut of all fines and forfeitures. This could amount to many times the annual salary of a customs

official.

11

Entire shipments could even be impounded if any part of the cargo was improperly disclosed. As noted by historian Andrew Wender Cohen, this was most dramatically illustrated in the winter of 1872–73, when customs agents discovered that the New York firm Phelps, Dodge and Company had undervalued its imports by $6,658.78 and failed to pay $1,664 in duty. Customs consequently seized the entire shipment, valued at $1.75 million. The company ended up paying $271,000 in fines and duties in order to get its shipment back.

12

These financial incentives encouraged the same sort of overzealous enforcement that had so enraged colonial merchants in their dealings with British customs offices. In one bust alone, the collector of customs at the New York port reportedly pocketed $56,120—more than the annual salary of the U.S. president. The collector was Chester Arthur, who was so notorious for abusing the system that the president asked him to resign—and when he refused, it took years to force him out.

13

Arthur went on to become the twenty-first president of the United States and surprised his critics by turning into an advocate for civil service reform, including within customs.

In the face of mounting evidence of abuses and public outrage over unscrupulous profit-driven enforcement, the Grant administration finally abolished much of the moiety system in June 1874.

14

With the personal financial incentives and rewards for customs agents greatly reduced, enforcement noticeably loosened. Even as imports increased sharply, the amount collected from fines and forfeitures plummeted.

15

The New York customhouse, by far the nation’s largest, epitomized the excesses of patronage politics and the political spoils system. As one account of the history of the U.S. Customs Service describes it, “The office of the Collector of Customs at the Port of New York had become a prize second only in political prestige and influence to a Cabinet appointment.”

16

Customs often served as a jobs program to reward loyal political supporters, regardless of qualifications. And those hired through political favoritism, in turn, were expected to make regular financial contributions to the political party. As a congressional commission appointed to investigate the New York customhouse reported in 1877, the amount of political contributions was set on the basis of salary level, and that “some of them repair their diminished salaries by exacting or accepting from the merchants unlawful gratuities.”

17

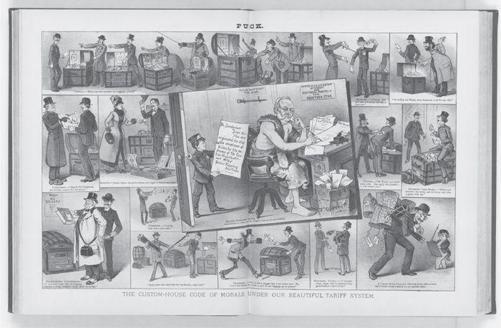

Figure 10.1 “The CustomHouse code of morals under our beautiful tariff system.”

Puck

, October 14, 1885. Political cartoon showing the many types of bribes offered to customs agents. (Library of Congress).

The New York customhouse came to symbolize corruption in a famously corrupt era. A standard scheme was for customs appraisers to take bribes from importers in return for undervaluing incoming goods.

18

“It is a fact more or less notorious among merchants,” reported the

New York Herald

, that the appraiser’s office within the customhouse “is rotten throughout.… The Place has become a disgrace even to the present administration.”

19

Foreshadowing the Progressive movement’s calls for reform decades later, in April 1877 the New York

Tribune

suggested that the city’s customhouse was so corrupt that it should be placed at the top of the list of government operations across the country most in need of reform.

20

Although the New York customhouse gained the greatest notoriety (partly due to its sheer size and importance), corruption also plagued the customhouse at other major ports. At the New Orleans customhouse, government investigators in 1877 found that the declared value of goods by importers was usually not questioned, and that there was “great elasticity of conscience” in such declarations—evident, for example, in keeping multiple sets of invoices (one reflecting the actual value of the goods, one below value used for entry, and one above value for selling the goods).

21

Special Treasury Department agents in San Francisco reported that in far too many instances “the luggage of passengers arriving from foreign ports were delivered to the owners without any examination, and that this was done by special order from the collector.” Consequently, “hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of merchandise is brought into San Francisco and passed without payment of duty.”

22

It was apparently common for passengers to bribe inspectors; as John Dean Goss wrote in his late-nineteenth-century survey of tariff administration, “the practice of bribe-taking, or the ‘acceptance of gifts’ by the inspectors from arriving passengers is very general, and produces a very demoralizing effect.”

23

Even as the New York customhouse faced mounting public complaints and charges of corruption, supporters rushed to its defense. In June 1871,

Harper’s New Monthly Magazine

published a glowing profile of the New York customhouse, portraying it as a victim of corrupt merchants: “It is the fashion of the day to speak derisively of Customhouse officials. They are supposed to be idlers, and, if opportunity offers, dishonest.” Nevertheless, “it should be remembered

that no dishonest customs official can exist unless he is seduced into his fraudulent course by some unprincipled merchant trader. And yet the press and the public opinion launch their condemnation of the poor clerk, but never breathe a word of censure upon the plotter of the mischief, and receiver of the lion’s share of the dishonestly obtained plunder.”

24

In June 1884,

Harper’s

followed up with another glowing profile, calling the New York customhouse “the greatest institution in the city,” noting that trade had almost doubled since 1866 and that most of this trade flowed through New York.

25

The city was indeed the leading beneficiary of the trade boom, becoming the world’s most important trading center by the turn of the century. Astonishingly, American imports and exports doubled between 1897 and 1907, with much of it flowing through the port of New York. “Commerce,” proclaimed an upbeat Charles King, the president of Columbia College, “is the interpreter of the wants of all other pursuits, the exchange of all values, the conveyor of all products.”

26

He could have added, “through both legal and illegal means.”

Smuggling in the American Dream

Whether by buying off, deceiving, or evading customs agents, smugglers managed to sneak in large quantities of untaxed goods. As one historian describes it, “Illegally imported goods from Europe, the Caribbean, and Asia filled store shelves, graced the dinner tables of fashionable houses, and swathed the bodies of chic women.”

27

Smuggling greatly contributed to America’s increasingly consumer-oriented and fashion-conscious society in the Gilded Age, an era defined by conspicuous consumption of foreign styles and tastes, imported both licitly and illicitly.

28

In New York social circles an appearance of cosmopolitanism was attained through imitation, and imitation was attained through importation. In this “golden age of New York society,” some high-society women ordered forty gowns from Paris every season, with each dress costing $2,500.

29

It should therefore be little surprise that in a period of both high tariffs and high consumption, some were tempted to keep up with changing fashion styles through tax-evading smuggling. As the

New York Times

reported, “In the Spring and in the Fall, when the styles change, there is always an epidemic of smuggling. The dressmakers,

buyers, and milliners who bring back the latest Paris styles are now the subjects of constant watch.”

30

One woman was even caught trying to use a fellow passenger to help her smuggle in her bridal outfit.

31

The customs commissioner estimated that in fiscal year 1872–73 36,830 travelers smuggled in goods worth $128,905,000 (the equivalent of $2.4 billion in 2010), though one must wonder how he could possibly have come up with such a precise number.

32

America in the Gilded Age, it seems, was not just a nation of shoppers but also a nation of illicit shoppers.

Illicit importers ranged from petty smugglers to major firms engaged in bulk smuggling. The former typically involved smuggling high-value and low-bulk items subject to heavy duties—such as jewelry, cigars, and watches—carried on the person or in personal luggage when returning from abroad.

33

The latter most often involved systematic undervaluing or false invoicing of commercial cargo, such as underestimating the weight of a shipment of sugar or bay oil, or listing highly dutiable silks and linens as cheaper cloth material.

34

For instance, in 1870 the

New York Times

reported that almost thirty “prominent firms” were accused of trading in smuggled bay oil, and in 1889 the paper reported on the near monopoly of the sugar trade by some twenty firms able to defraud the government and drive out competitors.

35

In 1877, the customhouse statistician Joseph Solomon Moore estimated that nearly $12 million in silk imports—some 25 percent of the total—was smuggled in.

36

In 1881, a leading New York silk manufacturer claimed that a majority of the duties on silk—which carried a 60 percent tariff—were routinely evaded through false invoicing.

37