Smuggler Nation (34 page)

Authors: Peter Andreas

Tags: #Social Science, #Criminology, #History, #United States, #20th Century

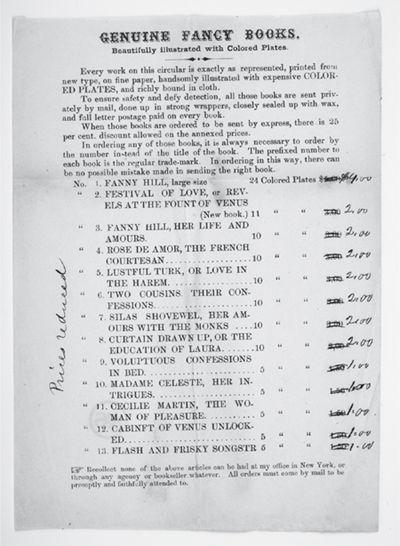

Figure 11.3. “Genuine Fancy Books.” Private circular advertising erotica, promising to make discreet deliveries through the mail in a manner that will “defy detection” (American Antiquarian Society)

Contraband Contraceptives

Obscene texts and pictures were not the only items banned. The Comstock Act extended the definition of obscenity to include all devices and information related to contraception or abortion as well.

24

Imports were prohibited. When asked why birth control was added to the ban on obscenity, Comstock replied, “If you open the door to anything, the filth will all pour in and the degradation of youth will follow.”

25

But as was the case with obscene material, the import ban on contraceptives did more to stimulate domestic production than curb supply. This was strikingly evident in the story of the condom.

Until the 1850s, virtually all condoms were imported from Europe and made from animal intestines. They were also expensive, as much as a dollar per condom in the 1830s, making them unaffordable to most.

26

Condoms were often imported via smuggling, but to evade U.S. tariffs rather than prohibitions.

India Rubber World

, an American trade journal, reported that condoms were regularly “brought in from Europe, not as a regular import, but in small carefully-guarded packets that got by the customs officials without paying duty.”

27

Condom production was revolutionized in midcentury through a technical breakthrough—the vulcanization of rubber (which made rubber resistant to both melting and cracking)—patented in 1844 by the American Charles Goodyear. Skin condoms remained popular,

but the rubber revolution increased supplies, heightened competition, and drove down prices. By the early 1860s, a condom cost as little as a dime.

28

George Bernard Shaw even called the rubber condom “the greatest invention of the nineteenth century.”

29

Condoms were not only more affordable than ever by the time of the 1873 ban; they remained relatively cheap afterward, with the price of a rubber condom in 1887 still ten times less than that of the animal skin equivalent of a few decades earlier.

30

Curiously, the same year that condoms were criminalized and imports banned, the duty on legal imports of the animal intestines most commonly used to make skin condoms was lifted and never drew Comstock’s attention. As historian Jane Farrell Brodie writes, the prohibition on “the importation of contraceptives was never enforced against goldbeater’s skins [the outer membrane of calf intestines] or their molds, so that throughout the decades when the laws against reproductive control were most stringently enforced a constant supply of materials ready to be made into condoms was available.”

31

In other words, even as the importation of condoms was banned, the legal importation of skins for clandestine domestic condom manufacturing remained legal and was even facilitated by the lifting of the tariff. Predictably, this encouraged and enabled import substitution in the condom trade.

As was the case with pornography, the main effect of prohibition was to drive the birth control business underground, making it much less public and visible even as it continued to thrive. Compare, for example, advertising before and after the Comstock law. As Robert Jutte notes, “At the beginning of the 1870s … a third of all advertisements in the popular New York paper the

Sporting Times and Theatrical News

consisted of publicity for methods of abortion and contraception.”

32

One Manhattan-based firm advertised its wares as follows: “Best protectors against disease and accident. French rubber goods $6.00/dozen; rubber $4.00/dozen. Sample 30 cents. Trade supplied. Ladies protectors $3.00.”

33

The first advertisement for condoms appeared in the

New York Times

in 1861, but the Comstock law made such advertisements increasingly scarce. After 1873, information and knowledge about birth control continued to circulate, though much less freely. Advertising continued, using less candid and blunt language. Distributors protected themselves from the law by advertising products for their hygienic value

(such as “sanitary sponges for ladies”) rather than for their antipregnancy uses.

34

Some inventors even continued to apply for patents for birth control devices, but without directly labeling them contraceptives. Texas inventor Uberto Ezell applied for a patent in 1904 for a rubber “male pouch,” which was a condom in all but name, described as a device to “catch and retain all discharges coming” from the “male member.”

35

The patent was approved in 1906.

Comstock’s crusade was noticeably selective, typically targeting lower-class immigrants while turning a blind eye to the rich and respectable.

36

This latter group included Samuel Colgate, the president of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice; his New Jersey soap company was the exclusive manufacturer of Vaseline, a petroleum jelly advertised as a safe contraceptive aid to help kill sperm.

37

Other major companies—notably Goodyear; Goodrich; and Sears, Roebuck and Co.—advertised contraceptives without attracting the ire of Comstock and his antivice agents. They escaped scrutiny partly because contraceptives were never more than a marginal part of their commercial profile. This created space for smaller players to participate in the riskier and more criminalized business of mass distribution. The prohibitionist climate inhibited larger firms from making contraceptives a core part of their business and thus taking over the market.

38

At the high end of the contraband condom business, the best and most reliable products continued to be shipped in from Europe.

39

But the mass-produced stuff was increasingly domestic. Clandestine condom production (both rubber and skin) required minimal start-up costs, and the product itself was highly portable, profitable, concealable, and in great demand—an ideal commodity in a dispersed and decentralized black market. As was the case with pornography, illicit distribution was facilitated by the increasingly efficient and inexpensive U.S. mail system. In the end, it was not Comstock but rather the invention of latex in the 1920s, as well as new FDA regulations, mass production, and product standardization in the 1930s, that pushed small-time entrepreneurs out of the business.

40

Until then, criminalization had a democratizing effect on the market, creating a profitable niche for small-time entrepreneurs—many of them immigrants—who were otherwise relegated to the margins of society. For those willing to take the

risks, the commerce in contraband contraceptives offered few barriers to entry and provided an alternative avenue of upward mobility.

41

Take the remarkable career of Julius Schmidt, a young Jewish immigrant from Germany who started out making animal-intestine condoms on the side while working at a meat-processing plant in New York. Harassed, arrested, and fined by Comstock, Schmidt nevertheless managed to build up an underground condom business that would not only survive but thrive. Despite raids on his home, Schmidt continued to expand his business, and he listed “cap manufacturer” as his occupation on the 1890 census.

42

Decades later,

Fortune

magazine would dub him the king of the American condom empire—without mentioning his criminal past. Changing his last name to Schmid, he also became the top condom supplier to the U.S. armed forces during World War II.

43

Many women also turned to birth control bootlegging at a time when their economic opportunities were few and far between.

44

This included, for instance, Antoinette Hon, a Polish immigrant who specialized in mail order distribution of “womb suppositories” and “douching powders” from her base in South Bend, Indiana.

45

In the case of Margaret Sanger, birth control (a term she coined) was a cause rather than a business. Credited as the founder of the American birth control movement, she repeatedly defied and evaded Comstock in the waning years of his campaign. She was arrested multiple times, in 1916 for opening the country’s first birth control clinic, which landed her in jail for thirty days. On several other occasions, she fled to Europe to avoid arrest. It was during these overseas trips, including to the Netherlands, where she expanded her knowledge about birth control practices, that she developed many of her core views.

46

Sanger also colluded with her husband, James Noah Slee, to smuggle Mensinga diaphragms into the country. Slee, the president of the Three-in-One Oil Company, used the cover of his business to ship the diaphragms from Europe to Montreal, and from there the shipments were smuggled across the U.S.-Canada border hidden in the company’s oil drums. Sanger resorted to this smuggling scheme not only to evade the prohibition on contraceptives but also to avoid dealing with domestic black marketeers such as Schmid, whom she viewed as too commercially oriented.

47

As was the case with catching pornography traders, Comstock and his agents relied heavily on undercover purchases and buy-and-bust sting operations. But their effectiveness was limited by privacy protections and court rulings against entrapment. Much to Comstock’s frustration and dismay, judges and juries tended to have a more lenient and less punitive attitude toward bootleg birth control than toward smut smuggling.

48

There were far fewer arrests and convictions for the former than the latter. Comstock’s agents made fewer than five arrests related to birth control per year between March 1873 and March 1898.

49

So despite Comstock’s crusading efforts, black market contraceptives remained widely available at relatively affordable prices.

50

It is striking that the national fertility rate was declining at the same time as Comstock was busily trying to suppress contraception and abortion. Although extremely difficult to measure, it is not unreasonable to speculate that black market supplies played a role in the country’s declining birthrate. Abortion was obviously not a form of smuggling, but importing and distributing information and devices related to abortion certainly was.

51

World War I proved to be a decisive turning point in the battle over contraband contraceptives. In the context of war, concern about the spread of sexually transmitted diseases was elevated to the status of a security threat, for which the condom was increasingly viewed as an urgently needed shield. The logistical challenge, however, was that Germany was Europe’s largest producer of rubber condoms. Cut off from German supplies, Allied troops looked to alternative sources—including from outlawed U.S. producers such as Schmidt—who now also became illicit exporters for the war effort in Europe. The American company Youngs Rubber began to produce the now-famous Trojan brand of condoms in 1916. As Merle Youngs, the company’s founder, later acknowledged, the war generated “a tremendous demand … for these little articles.”

52

According to Youngs, condoms were “unofficially” sold in many government-run canteens despite the military’s official stance of prohibition. More than four million American men took part in World War I, and they brought back both greater familiarity with and acceptance of condom use.

53

Growing anxiety and concern about venereal disease ultimately trumped Victorian taboos and legal prohibitions. Legal rulings began to

roll back the Comstock law. In 1918, Judge Frederick Crane overturned a conviction against Sanger, ruling that condom use was legal and not “indecent or immoral” if prescribed by a doctor to prevent disease. But since there was no real enforcement of the prescription requirement—condoms marked “for the prevention of disease only” could even be bought at pool parlors and gas stations—the need for a medical justification was moot.

54

In a July 1930 New York court of appeals ruling, producers of contraceptives who promised to sell only to licensed doctors and druggists were exempted from federal prosecution.

55