Sisters in Spirit: Iroquois Influence on Early Feminists (8 page)

Read Sisters in Spirit: Iroquois Influence on Early Feminists Online

Authors: Sally Roesch Wagner

BOOK: Sisters in Spirit: Iroquois Influence on Early Feminists

7.7Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Until woman’s rights advocates began to change divorce laws in the last half of the nineteenth century, women found themselves trapped in marriage, unable to leave. Women fleeing from a violent or abusive husband could be returned to him by the police, as runaway slaves were returned to their master. Husbands could will away an unborn child, and the baby would be taken from its mother and given to its “rightful owner” when the father/guardian died. And, until married women’s property acts were slowly enacted state by state throughout the nineteenth century, any money a wife earned or inherited belonged outright to her husband.

A married woman was “nameless, purseless and childless,” Stanton summed up, even though she be “a woman, heiress and mother.” Calling for an end to this injustice, the early suffragists were labeled hopeless dreamers for imagining a world so clearly against nature; worse, they were labeled heretics for daring to question God’s divine plan. Stanton, whose major work,

The Woman’s

Bible,

was published in 1895, became convinced that the oppression of women was not divinely inspired at all. Gage agreed, calling the church the “bulwark” of women’s oppression.

The Woman’s

Bible,

was published in 1895, became convinced that the oppression of women was not divinely inspired at all. Gage agreed, calling the church the “bulwark” of women’s oppression.

When the religious right tried to destroy religious freedom by placing God in the Constitution and prayer in public schools and by pushing a conservative political agenda in the 1890s, Stanton and Gage (Mott had died) determined to challenge the church. Their theory held that indigenous women in early history held positions of respect and authority in egalitarian and woman-centered societies that often worshiped a female deity, sometimes in combination with a male consort. This matriarchal system was overthrown, Stanton contended, when “Christianity, putting the religious weapon into man’s hand, made his conquest complete.”

22

While common knowledge held that Christianity and civilization meant progress for women, Stanton and Gage disagreed.

A Vision of Responsibilities22

While common knowledge held that Christianity and civilization meant progress for women, Stanton and Gage disagreed.

A few years ago I was invited to lecture at the annual Elizabeth Cady Stanton birthday tea in Seneca Falls along with Audrey Shenandoah, an Onondaga nation Spiritual leader. A crowd of my feminist contemporaries packed the elegant, century-old hotel, and I spoke about the rights of Haudenosaunee women. Then Audrey talked matter-of-factly about the responsibilities of clan mothers, who continue to nominate, counsel, and keep in office their clan’s chief, as they always have. In the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy, she explained, Haudenosaunee women have worked with the men to successfully guard their sovereign political status against persistent attempts to turn them into United States citizens. In Audrey’s direct and simple telling, the social power of the Haudenosaunee women seemed almost unremarkable. “We have always had these responsibilities,” she said.

23

23

My feminist terminology, I suddenly realized, had revealed my cultural bias. Out of habit I had referred to women’s empowerment as women’s “rights.” But for Haudenosaunee women who have maintained many of their traditional ways despite two centuries of white America’s attempts to “civilize and Christianize” them, the concept of women’s “rights” has little actual meaning. To the Haudenosaunee, it is simply their way of life. Their egalitarian relationships and their political authority are a reality that I—like my foresisters—still but dream.

Mother Earth Does Not Revolve Around the SonI arrive, hurried, at the home of Ethel, a friend with whom I work. We have exactly an hour to meet, squeezed into a tight travel schedule. After pleasantries we get down to business, moving along at a smooth clip, and it looks as if we will finish on time when suddenly her son enters. A strapping 17-year-old, he fills the room with his presence. Ethel beams at him and hangs on his every word as he describes his teachers’ deadlines, clean uniform needs, other mundane details of his day. Virginia Woolf got it right: his mother’s admiring gaze reflects him twice life size. He never acknowledges my presence, she doesn’t introduce us, and our work is forgotten. When finally he walks out, Ethel and I scramble to tie up loose ends, some of which still dangle as I dash out the door.Ethel is EuroAmerican; her son stands poised to inherit the world.A week later I sit in my friend Jeanne’s living room, enjoyably chatting. I hear her 17-year-old son in the kitchen rattling pans, perhaps cooking or washing dishes. Minutes later he appears and places cups of tea in front of us without a word, his gift offered unobtrusively, his demeanor without display. I look up to thank him but he is gone, his back already turned as he repairs to the kitchen. Jeanne seems not even to notice, and our conversation continues.Jeanne is Onondaga, a Haudenosaunee woman descended from the traditional “pagan” Iroquois—those who refused to be “Christianized” and “civilized.” Her son recognizes his mother, and all women, as the center of the culture.Such sons of such mothers belonged to our feminist foresisters’ vision too. They are sons who learned from their fathers and their father’s fathers to respect the sovereignty of women. They are sons of a tradition in which rape and battering of women was virtually unknown until contact with white people, a tradition in which women’s rights are a birthright.

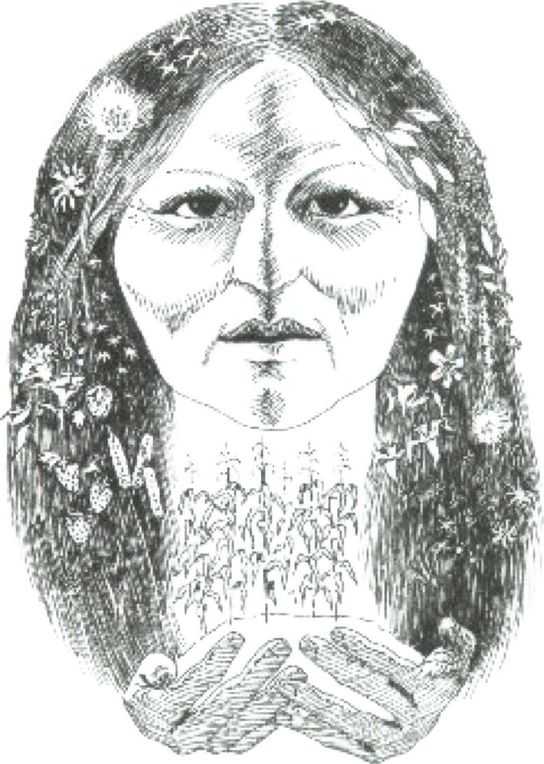

Mother Earth, Creator of Life

Haudenosaunee women were farmers. What an amazing revelation this must have been to reformers accustomed to a society where women were corseted, fashionably weak, and believed to be incapable of hard labor. Nodding their tacit approval to the prevailing social, legal and religious wisdom, most white women of means accepted their place: inside the home. Not Native women, who farmed, Gage marveled, and who did so using highly effective methods unknown to white men.

Their method of farming was entirely different from our own. In olden Iroquois tillage there was no turning the sod with a plough to which were harnessed a cow and a woman, as is seen today in Christian Germany; but the ground was literally ‘tickled with a hoe’ and it ‘laughed with a harvest.’ Corn hills three or four times larger than those seen today remained in use successive years, and when the country was first settled the appearance of those numerous little mounds created great wonder. Slightly scratched with a stick or piece of bone, maize was there planted, and but little labor attended its cultivation.

1

Haudenosaunee women planted primarily corn, beans, and squash. Harriet Maxwell Converse (Gage’s friend) explained that this nutritionally perfect combination was the staple of their diet:

The three vegetables, the corn, beans and squash were known to the Onondagas as tu-ne-ha-kwe meaning ‘these we live on,’ and to the Senecas as Dio-he’-ko, meaning ‘our true sustenance.’ It is interesting to note that among the ancient Aztecs the spirit of the maize was called Tonacayohau, She Feeds Us.

2

Arthur C. Parker (of Seneca descendent), an acquaintance of Susan B. Anthony and an early Director of the Rochester Museum of Arts and Science (now the Rochester Museum and Science Center), explained the method of planting used by the women:

The Iroquois generally planted their squashes in the same hills with corn and some kinds of beans. Besides the land and labor saved by this custom there was a belief that these three vegetables were guarded by three inseparable spirit sisters and that the plants would not thrive apart in consequence.

3

The spiritual harmony of the Three Sisters is also ecological. The corn stalk provides support for the beans while the beans provide nitrogen to nourish the corn. The squash covers the mound, keeping weeds out and moisture in. Eaten together, these Three Supporters constitute a nutritionally balanced diet.

Native women’s honored obligation, recognized by the men, was to direct the home and the community’s agriculture. Satisfying and sacred, women’s work harmoniously complemented the hunting/diplomatic duties of men; both were equally valued. Within this framework of community responsibility, individual liberty flourished.

Gage knew about Mary Jemison, the white captive adopted into the Seneca nation who, when given the option of returning to the white world, chose instead to live with her Native family. Jemison’s story was recorded by a Dr. Seaver and made into a popular book during Gage’s childhood. Although she was eighty at the time the book was issued, Jemison still planted, tended, and harvested her corn, gathered and chopped her own wood, and fed her cattle and poultry, wearing the traditional dress. Jemison offered a detailed description of Seneca women’s agricultural work:

Our labor was not severe; and that of one year was exactly similar in almost every respect to that of the others.... Notwithstanding the Indian women have all the fuel and bread to procure, and the cooking to perform, their task is probably not harder than that of white women, who have those articles provided for them, and their cares certainly are not half as numerous, nor as great. In the summer season, we planted, tended, and harvested our corn, and generally had all of our children with us; but had not master to oversee or drive us, so that we could work as leisurely as we pleased.... We pursued our farming business according to the general custom of Indian women, which is as follows: In order to expedite their business, and at the same time enjoy each other’s company, they all work together in one field, or at whatever job they may have on hand. In the spring, they choose an old active squaw [sic] to be their driver and overseer, when at labor, for the ensuing year. She accepts the honor, and they consider themselves bound to obey her.... By this rule, they perform their labor of every kind, and every jealousy of one having done more or less than another is effectually avoided.

4

In a newspaper report that she published on the 1875 Onondaga County Indian Fair, Gage marveled that “forty-eight kinds of beans were on exhibition.” She went on to give some history of Haudenosaunee agriculture:

A Dutch history of the New Netherlands as early as 1621 speaks of the luxuriant growth of Turkey beans. Planted in hills with corn they twined around the stalks. Hendrick Hudson in 1609 saw at one place more than three shiploads of corn and beans drying, beside the crops still luxuriantly growing. It was no lack of other food that forced the Five Nations into agriculture; all kinds of game were abundant.... Turkeys, geese, ducks, swan, teal, plover, pheasants, deer, bear, beaver and many other kinds of game were equally abundant, besides an infinite variety of nuts and wild fruits. But this confederacy, with its wonderful government and customs and its fixed dwelling places, had in its own steps of progress developed a science of agriculture. Corn, beans, potatoes, and plants of the gourd family, including squash and a species of pumpkin, and tobacco, were all regularly cultivated, and together with vast quantity of nuts, were stored in pits or cellars for winter use.

5

Other books

Excessica Anthology BOX SET Winter by Edited by Selena Kitt

A Touch of Betrayal by Catherine Palmer

The Laird's Kidnapped Bride by Mysty McPartland

Forget-Her-Nots by Amy Brecount White

Hijos del clan rojo by Elia Barceló

How to Be English by David Boyle

Straightening Ali by AMJEED KABIL

Child of Earth by David Gerrold

The Sword by Gilbert Morris

Desert Hearts by Marjorie Farrell