Sisters in Spirit: Iroquois Influence on Early Feminists (4 page)

Read Sisters in Spirit: Iroquois Influence on Early Feminists Online

Authors: Sally Roesch Wagner

BOOK: Sisters in Spirit: Iroquois Influence on Early Feminists

12.25Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Clear as she was about the Old World perspective, Gage did not understand the distinction between tribes and nations. Harriet Maxwell Converse, a friend of Gage, did. Converse explained that the difference between tribes and nations was one “not generally understood, the two terms being frequently confounded.” The significance rested in nation sovereignty. Converse explained: “The Seneca Nation is ... as distinct among Indians as France, Germany, and England are distinct among the nations of Europe.”

19

Language, she understood, has critical political consequences. Treaties were made with sovereign American Indian nations, not with tribes. However, if no “nations” are recognized, there are no treaties, and the use of the word

tribe

instead of

nation

has the political effect of erasing treaty obligations.

What Do We Call the People Who Influenced the Suffragists?19

Language, she understood, has critical political consequences. Treaties were made with sovereign American Indian nations, not with tribes. However, if no “nations” are recognized, there are no treaties, and the use of the word

tribe

instead of

nation

has the political effect of erasing treaty obligations.

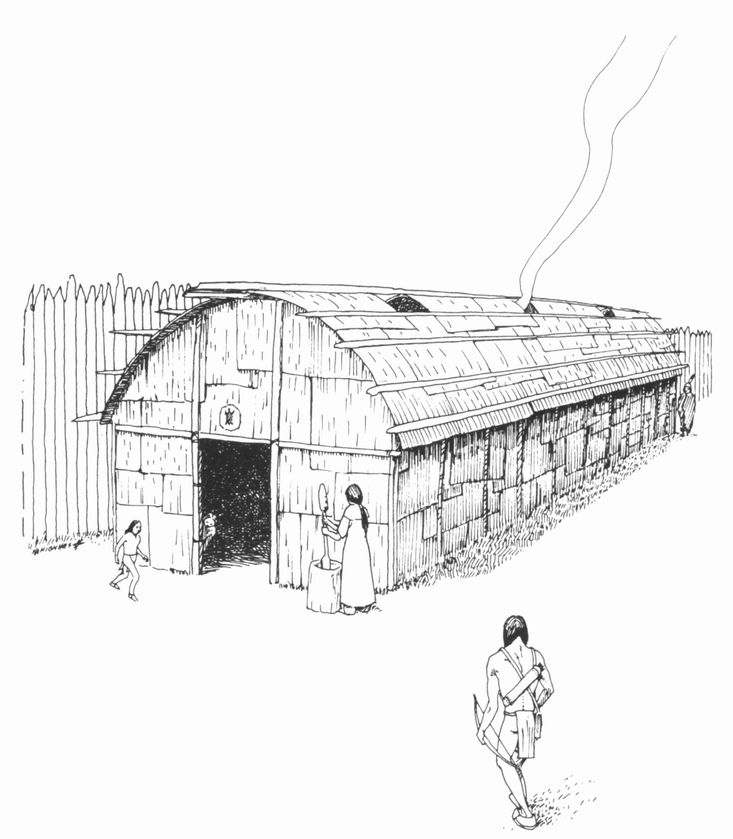

Having identified the need to find the missing players, we ask, who it is that may have influenced the suffragists? Once we identify them, we run into the question of name. The quick reply, “the Iroquois,” uses an imposed name, not the name the people call themselves, which is the “Haudenosaunee, the People of the Longhouse.”

“The Six Nations,” Converse told her readers, comprised “one of the most powerful confederacies ever known.” It “included the Onondagas, the Cayugas, the Senecas, the Mohawks, and the Oneidas. The Tuscaroras were added in 1723. The name Iroquois was not their proper Indian name but was derived, I believe, from the French and has been used instead of Ho-de-man-san-ne.”

20

[Her spelling] Converse’s description clarified not only the proper name but the confusion that resulted from the Five Nations Confederacy adding a sixth nation after its founding, when the Tuscaroras, after nearly being destroyed by colonists, took safety under the tree of peace and joined the Confederacy.

20

[Her spelling] Converse’s description clarified not only the proper name but the confusion that resulted from the Five Nations Confederacy adding a sixth nation after its founding, when the Tuscaroras, after nearly being destroyed by colonists, took safety under the tree of peace and joined the Confederacy.

New York Governor DeWitt Clinton spelled the name, Ho-de-no-sau-nee, which meant “the People of the Longhouse, from the circumstance that they likened their political structure to a long tenement or dwelling.”

21

21

Gage recognized another name the Haudenosaunee use for indigenous people: “To themselves the Five Nations were known as the Ongwe Honwe, that is, a people surpassing all others.”

22

22

“The Iroquois call themselves the

real people,”

Minnie Myrtle wrote, “and in speeches or conversation, if allusion is made to white people, they say invariably ‘our younger brethren.’”

23

real people,”

Minnie Myrtle wrote, “and in speeches or conversation, if allusion is made to white people, they say invariably ‘our younger brethren.’”

23

It is instructive to find that these self-chosen, inclusive names, well known to non-Natives a hundred years ago, have somehow become lost in the dusty archives and seldom appear in books today.

Haudenosaunee is the name (and accepted spelling today) for the Six Nations of the Confederacy, but it is not recognizable to most non-Native people, so completely has the power to name been usurped. Should we use the self-chosen name, knowing few will understand or should we use the imposed name that has nearly universal recognition? A third option presents itself: use both. We could begin with the commonly recognized name, Iroquois, and follow it with the chosen name in parentheses, like this:

The Iroquois (Haudenosaunee) Influence on

the Early

Woman’s Rights Movement.

However, parentheses are an aside, a brief interruption in the flow of the narrative. Notice the difference when we present the names the other way around:

The Haudenosaunee

(Iroquois) Influence on the

Early Woman’s Rights Movement.

Haudenosaunee now stands as the proper term; the word Iroquois is included to assist those who do not recognize it.

Language Evolves to Reflect the Way People ChangeThe Iroquois (Haudenosaunee) Influence on

the Early

Woman’s Rights Movement.

However, parentheses are an aside, a brief interruption in the flow of the narrative. Notice the difference when we present the names the other way around:

The Haudenosaunee

(Iroquois) Influence on the

Early Woman’s Rights Movement.

Haudenosaunee now stands as the proper term; the word Iroquois is included to assist those who do not recognize it.

Savage

—a EuroAmerican word implying a lower degree of civilization—was widely used in the 19th Century to describe Native people.

—a EuroAmerican word implying a lower degree of civilization—was widely used in the 19th Century to describe Native people.

The name the people call themselves, which is the “Haudenosaunee, the People of the Longhouse.”

How did this word pass out of use? We look to the suffragists and their acquaintances for a part of the answer.

Minnie Myrtle lived with Laura and Ashur Wright, missionaries to the Seneca nation whose writings were quoted by Stanton. Myrtle questioned the use of the term “savage” in her popular 1855 book,

The Iroquois;or, The Bright Side of Indian Character:

The Iroquois;or, The Bright Side of Indian Character:

A people like the Iroquois who had a government, established offices, a system of religion eminently pure and spiritual, a code of honor and laws of hospitality excelling those of all other nations, should be considered something better than savage, or utterly barbarous.

Myrtle quoted an eminent Spanish legal authority, Zurita, who spent nineteen years among the Aztecs, and was as indignant that they should be called barbarian as she was when the Haudenosaunee were similarly labeled:

It is an epithet which could come from no one who had personal knowledge of the capacity of the people or their institutions, and which in some respects is quite as well merited by Europeans. If the Aztecs did not deserve the term barbarians, surely I shall be thought just in denying the term savage to belong to the Iroquois; and from their mythology, if nothing else, it is evident that they were destitute neither of genius nor of poetry.

24

Eventually such challenges to the white supremacy embedded in the word

savage

caused the term to drop from common usage. The presence of equally offensive words in our present language reveals how far we have yet to go in our evolution toward equality.

savage

caused the term to drop from common usage. The presence of equally offensive words in our present language reveals how far we have yet to go in our evolution toward equality.

Squaw,

an insulting slang term which French fur trappers created from an Algonquin word referring to female genitalia, is an example of a word on its way out of the English language. Two teenage Ojibwa girls led a successful crusade to have Minnesota remove the word from all place names in the state. The issue is not new. Native American women have been protesting the use of the offensive term for at least a hundred years, as this 1890 story in the

Onondaga Standard

demonstrates:

an insulting slang term which French fur trappers created from an Algonquin word referring to female genitalia, is an example of a word on its way out of the English language. Two teenage Ojibwa girls led a successful crusade to have Minnesota remove the word from all place names in the state. The issue is not new. Native American women have been protesting the use of the offensive term for at least a hundred years, as this 1890 story in the

Onondaga Standard

demonstrates:

By the way, a little note here will not be found out of place to those readers who expect at some future day to come into contact with Indians, when they shall have to, perhaps surrender all the nicety of good usages to appear favorable in the estimation of the Indians, only to be embarrassed by the horrible outbreak of calling an Indian woman ‘Squaw,’ and find when too late two piercing jet black eyes resting upon some troubled countenance, as much as to say, “What is a squaw? Why do you call me a squaw? You are a squaw yourself! It is a vulgar expression; don’t use it; the Indians don’t use it; why should others? ”

25

The Oregon Geographic Names Board is changing the name of a prominent peak from Squaw Butte to Paiute Butte. A South Dakota official faced sanctions from the Governor for telling a joke using the insulting term. Within our children’s lifetime, we will probably see this offensive word eliminated from public use. Unfortunately, many suffragists must not have been aware of its meaning, for they used the word. It will appear in this book as they wrote it with a [sic] beside it to remind us of its inappropriateness.

Haudenosaunee Women: An Inspiration to Early Feminists

The woman’s rights movement was born in the territory of the Haudenosaunee in 1848. Were the suffrage leaders influenced by Native women? Was there a connection between the authority and responsibilities held by Haudenosaunee women and the vision of the woman’s rights movement?

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Matilda Joslyn Gage, and Lucretia Mott were among the leaders of the woman’s rights cause. Stanton and Mott organized the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention. Gage joined the movement in 1852 along with Susan B. Anthony. During her lifetime, Gage was recognized as the third member of the suffrage leadership “triumvirate” with Anthony and Stanton, but today she is less well known. Recognizing Gage’s formative role in developing feminist theory opens a new story of women’s rights.

Gage wrote extensively about the Haudenosaunee, especially the position of women in what she termed their “matriarchate” or system of “mother-rule.” She was working on a book about the Haudenosaunee when she died in 1898. In 1875, while president of the National Woman Suffrage Association, Gage wrote a series of newspaper articles on the Haudenosaunee. The editor of the

New York Evening Post

said that Gage expressed “an exhibition of ardent devotion to the cause of women’s rights which is very proper in the president of the... Suffrage Association and gives prominence to the fact that in the old days when the glory of the famous confederation... was at its height, the power and importance of women were recognized by the allied tribes.”

1

New York Evening Post

said that Gage expressed “an exhibition of ardent devotion to the cause of women’s rights which is very proper in the president of the... Suffrage Association and gives prominence to the fact that in the old days when the glory of the famous confederation... was at its height, the power and importance of women were recognized by the allied tribes.”

1

Spanning a 20-year period, Gage introduced readers to the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy in articles, the newspaper she edited

(The National Citizen and Ballot Box,

1878-1881) and her magnum opus

(Woman, Church

and State,

1893). She explained the form of government of the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora and their confederacy of peace.

(The National Citizen and Ballot Box,

1878-1881) and her magnum opus

(Woman, Church

and State,

1893). She explained the form of government of the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora and their confederacy of peace.

The famous Iroquois Indians, or Six Nations, which at the discovery of America held sway from the Great Lakes to the Tombigbe river, from the Hudson to the Ohio... showed alike in form of government, and in social life, reminiscences of the Matriarchate.

2

The clarity of understanding of Indian nation sovereignty that Gage displayed in an editorial in her newspaper in 1878 is a source of wonder to Native people today:

Our Indians are in reality foreign powers, though living among us. With them our country not only has treaty obligations, but pays them, or professes to, annual sums in consideration of such treaties.... Compelling them to become citizens would be like the forcible annexation of Cuba, Mexico, or Canada to our government, and as unjust.

3

Matilda Joslyn Gage and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, the major theoreticians of the woman’s rights movement, claimed that the society in which they lived was based on the oppression of women.

Haudenosaunee society, on the other hand, was organized to maintain a balance of equality between women and men. Shown here are the contrasting differences between the two worlds of women who lived side-by-side in this region of upstate New York in 1848.

Other books

Daddy Dearest by Paul Southern

Those Endearing Young Charms by Marion Chesney

Eminencia by Morris West

The Blue Cotton Gown by Patricia Harman

The Builder (The Young Ancients) by Power, P.S.

Tomato Girl by Jayne Pupek

My Big Nose and Other Natural Disasters by Sydney Salter

Family Storms by V.C. Andrews

Calico by Callie Hart

All the Single Ladies by Jane Costello