Scene of the Crime (16 page)

Read Scene of the Crime Online

Authors: Anne Wingate

With that debacle, petty hoodlum Roscoe Pitts found his way into history. If he hadn't tried to get rid of his fingerprints, nobody would ever have heard of him.

Are Criminals too Smart?

I have heard people—even police officers—say that there has been so much publicity on fingerprints that criminals aren't dumb enough to leave them anymore. Fortunately, that is absolutely untrue. U.S. Department of Justice figures indicate that a constant minimum of one-third of all property crimes result in usable fingerprints, if police would just look for them. The sad fact, however, is that too many police have stopped looking for fingerprints, with the result that too many criminals are getting away with crimes they should not be getting away with.

When my house in Fort Worth was burglarized, it took me several telephone calls to get ident officers to come to the scene. When one finally showed up, she informed me in superior tones that it is impossible to get fingerprints from aluminum screen frames.

That was a lie; aluminum screen frames are one of the best surfaces. But I pretended to assume she was simply ill-informed; I explained my background, borrowed her fingerprint equipment, and lifted several beautiful prints, which I turned over to her. To the best of my knowledge, nothing was ever done with the prints—even when a couple of teenagers who had been burglarizing houses in my neighborhood were arrested.

I visited the Fort Worth ident office and learned why. Despite banks of stored fingerprint cards, they had one person working apparently only part-time on latent comparison, and apparently no attempt at nonsuspect identification was even being made.

Introducing AFIS

In real life,

every

burglary, robbery, recovered stolen auto, theft from auto, sexual assault by an unknown assailant, forgery, and counterfeiting—as well as any other crime in which the use of human hands was involved—should be followed, as soon as possible, by a diligent search for fingerprints. If this were done, and if all legible lifted fingerprints were then checked through AFIS—the Automated Fingerprint Identification System—the conviction rates in some areas would more than triple. In fiction, you may decide whether the department you're writing about does this right, does it in what police would call a half-assed manner, or does it not at all. If you're writing about a real department, find out how good a clearance rate (that is, what percentage of reported crimes are solved) the department has and how much use it makes of fingerprints. Ask politely; people tend to get defensive about these things. In writing about the Fort Worth Police Department, for fairly obvious reasons I tend to avoid mentioning fingerprints. My other series is set in a fictitious town, but it's near the real town of Galveston, and Galveston has a terrific ident section, which I mention fairly often.

Suspect Ident, Nonsuspect Ident

What is the difference between a suspect ident and a nonsuspect ident?

In a suspect ident, a suspect has been developed by other means, and all the identification technician has to do is to com

pare the latent with one fingerprint card. Anyone who cannot make an ident in that way has no right to call himself or herself an identification technician.

In a nonsuspect ident situation, there is no evidence except the lifted latent. The identification technician must search the latent—that is, compare the latent to a set of fingerprint cards. In Albany, Georgia, we maintained separate sex-crime files and burglar files, so that the print would be searched through the appropriate files (a robber would usually be found in the burglar file, as few people graduate to robbery without first trying burglary). Only in extraordinary cases would we search the entire files; comparing a single print to 10,000 or more fingerprint cards by hand is a monumental task.

Prior to AFIS, even a large police department identification section making as many nonsuspect idents a month as Doc and I were would have had the right to preen. But now, with AFIS, a police department of any size at all that is not making at least twenty to thirty idents a month must be considered lazy or ignorant. One identification officer proudly told me that his department had about a 15 percent ident rate; that is, they made idents on about 15 percent of all latents lifted. That sounded pretty good to me—until I found out his department, in a town eight times the size of Albany, was making fewer latent lifts than Doc and I had been making idents.

How AFIS Works

Let's step back for a moment and talk about fingerprints themselves.

And why do I want to do this? Because a mystery writer can be made to look extremely stupid if s/he misdescribes fingerprints. My dear friend Elizabeth Linington/Lesley Egan/Dell Shannon once severely misdescribed a fingerprint in one of her novels. I gave her a book about fingerprints. In her next novel, she described a "tented whorl." There is no such thing.

Fingerprint Types

There are three main types of fingerprints:

arches, loops

and

whorls.

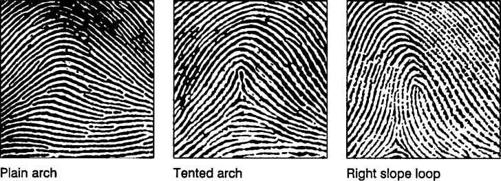

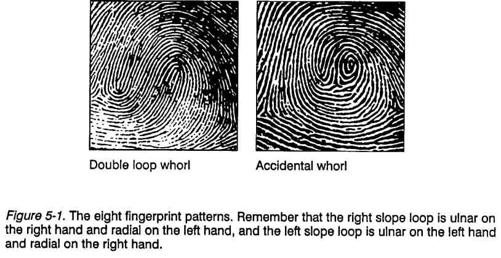

About 35 percent of all fingerprints are whorls; about 5 percent of all fingerprints are arches; and about 60 percent of all fingerprints are loops. These are subdivided into plain arches and tented

arches; radial loops and ulnar loops; and plain whorls, double loop whorls, central pocket loop whorls, and accidentals. People often have different patterns on different fingers; whorls are most often found on the thumbs, and arches are most often found on the index and middle finger. Now let's have a look at some of these patterns.

Figure 5-1 illustrates the eight different fingerprint patterns. The drawing of the radial and ulnar loops assumes that the prints are from the right hand; in fact, a radial loop is one in which the direction of flow tends to be in the direction of the thumb, and an ulnar loop is one in which the direction of flow tends to be in the direction of the little finger. Ulnar loops are far more common than radial loops, and radial loops tend most commonly to be found only on the index or index and middle fingers.

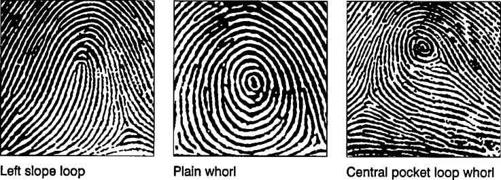

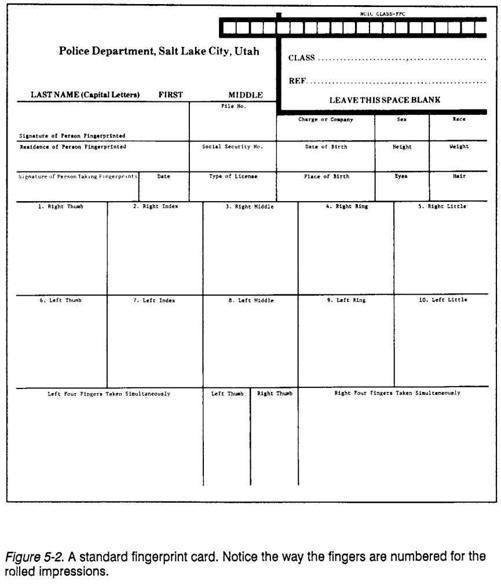

There are 1,024 possible primary classifications of fingerprints—and where do we get the primary classification? Figure 5-2 is the rolled print portion of a fingerprint card; remember that below it will be the plain—nonrolled—prints, with all four fingers on each hand printed together, the left hand first, then the left thumb, then the right thumb, then the right four fingers.

The top number in this chart is the finger number. All fingerprint cards use the same finger numbers, so that the prints are always taken in the same order and so that an identification technician will always know, for example, that the number 1 finger is the right thumb and the number 10 finger is the left little finger. Each numbered finger is given a numerical value as shown above, but only the whorls are counted. Arches, tented arches and loops are called "nonnumbered" patterns. The primary classification appears as a fraction, with the sum of the first number in each set of two—that is, fingers number 1, 3, 5, 7 and 9—plus a 1 which is added to each set of numbers, as the denominator and the sum of the second set of numbers—fingers 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10—plus the added 1 as the numerator. For example, suppose that we have whorls on both thumbs and loops everywhere else (this is an extremely common pattern). The primary classification would have a denominator of 16 (from the right thumb, finger #1) plus 1 (the additional 1), or 17, and a numerator of 4 (from the left thumb, finger #6) plus 1 (the additional 1) of 5 —hence, 5/17. The single most common primary classification, taking in over half of all fingerprint patterns, is 1/1 — that is, there are no whorls at all; therefore, none of the numerical values count except the additional 1 which is always added.

You don't have to understand this. You don't even have to try. I have explained it in far greater detail than this to people who then stare at me and exclaim, "That's impossible."

The entire FBI fingerprint classification system—a major refinement of the Henry system—with all its primaries, secondaries, subsecondaries, sub-subsecondaries, finals and so forth, is extremely complicated; even some fingerprint technicians do not understand it fully, and there is no earthly reason to give it here. If you really want to learn it, get a copy of the FBI fingerprint handbook

The Science of Fingerprints,

available from the United States Government Printing Office for about eight dollars; several other very fine fingerprint books are listed in the bibliography.

The NCIC System

The NCIC fingerprint system, although it is based on the Henry system, is not quite the same. We need to get to a little more information before explaining it.

Figure 5-3 shows a loop pattern, with arrows pointing to the

delta

and the

core.

A loop is measured by counting the ridges intervening between the delta and the core.

Figure 5-4 shows a whorl pattern. Whorls theoretically always have at least two deltas (only the very rare

accidental whorl

can have more than two deltas); in fact, as most fingerprint people know, some whorls do not have two deltas. But a whorl is measured by tracing the ridge from the left delta. If it goes more than two ridges inside the right delta, as this one does, it is an

inner trace whorl.

If it meets the right delta within two ridges one way or the other, it is a

meeting trace whorl.

If it goes more than two ridges outside the right delta, it is an

outer trace whorl.

Arches and tented arches are not measured.

For an NCIC classification, a fingerprint would be listed as follows: