Scene of the Crime (27 page)

Read Scene of the Crime Online

Authors: Anne Wingate

Let's get to some definitions now.

Serology

is the study of blood and other body fluids;

forensic serology,

of course, is the study of blood and body fluids in a criminal situation.

Electrophoresis

is a method of identifying chemicals by analyzing a small amount that has been burned.

Chromatography

and

spectrometry

are methods of identifying chemicals by using mixed chemical and computerized tests; the resultant colored bar graphs allow exact determination of chemicals present and their concentrations. We talked about atomic absorption analysis, also called neutron activation analysis, in reference to firearms evidence.

And what can scientists determine from all these tests? It's obvious, of course, that they can discover such things as what chemicals are present in or on the body and in what proportions. From stains left by the assailant on the victim, they may be able to determine sex and blood type of the assailant. If the victim yanked out some of the assailant's hair, very often scientists can determine the sex of the assailant from the hair (if it was not otherwise apparent).

By determining the trajectory of the knife or gun, the pathologist may determine the height of the assailant, the distance the assailant was from the victim, the handedness of the assailant. The trajectory is determined by the path the bullet or knife took through the clothing and through the body. But sometimes things get complicated in this area.

Unusual Problems

Hans Gross says that "it is possible to find large gun-shot wounds, while the dress covering them is not in the slightest degree injured." I would not believe this statement for a second, were it not for the case of Jack. (Remember the names are changed.)

This case occurred while I was still detective bureau secretary;

in fact, it was in the first few months, and the department had yet to learn that I am not unduly squeamish. Jack ran a small barbecue restaurant in a sleazy part of town. One evening, just about twilight, as he sat in his kitchen, listeners heard him involved in a loud quarrel. Then, quite suddenly, Jack got up and ran outside, apparently chasing the person he was quarreling with. Three shots were fired, and the next person to run outdoors found Jack on the ground dead, his pistol in his hand. His pistol had been fired twice. He had been killed by a shot from another pistol.

The body was hauled off to the emergency room, where detectives took custody of clothing before transferring the body to the morgue. The clothing was taken into the detective bureau. No crime lab yet existed in Albany, and the clothing was draped over chairs and a table in a witness room to allow the blood to dry. That was on Saturday.

On Monday, the chief of detectives went out in person to view the autopsy. About ten o'clock he called me from the morgue. There was a question about the trajectory of the fatal bullet, and he wanted me to go and examine the clothing. And here's where the whole thing got very, very complicated.

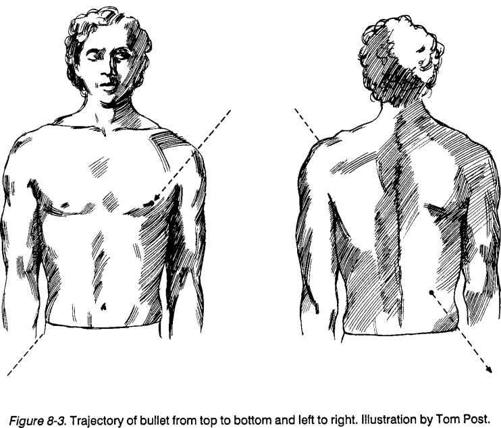

Jack had not been underdressed. He had on a bib apron, a button-up shirt, and a V-neck undershirt. The bullet had entered the left side of the chest at approximately the level of the nipple at a sharp angle, exiting on the right side below the rib cage (see Figure 8-3).

I examined the clothing carefully, and then I examined it again. There was not one trace of a bullet hole in any item of clothing. I went back to the phone and told Chief Summerford that. He told me I was too squeamish and sent me back to look again. I did, with the same results.

About ten minutes later, Chief Summerford, obviously furious, stormed in and searched the clothes himself—with the same results.

He decided maybe the bullet had parted the threads and gone through, allowing the cloth to close up once more. His wife, whose hobby was sewing, assured him that was impossible.

Because the trajectory of the bullet indicated that Jack had been shot by someone well above him as well as facing him, like maybe up in a tree, we looked at trees. There were some present, but there was no way whatever the person he chased out of his kitchen would have had time to climb one before the shots were fired.

I thought maybe Jack had tripped over a tree root just as his assailant shot; so he would have been leaning or falling forward with his apron, shirt and undershirt falling away from his body so that the bullet entered above all of the clothing. Chief Summerford, wiser than I in the ways of men's clothing, said that was nonsense.

The case was never cleared. About six months after the shooting, the pistol that had fired the fatal shot was found in an abandoned house. The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms managed over the next couple of months to trace the gun through about twenty owners, the last two of whom had stolen it. The last one of those said the gun was stolen from him. There was known to be bad blood between him and Jack, and he was nervous, but there wasn't quite enough to make a case.

After talking with him for hours, one of the detectives invited me to see whether I could get anything out of him. I went back into the witness room and told him that the police knew he was lying. He insisted he wasn't, but it was obvious even to me that he was. I finally said, "Look, we've got about enough to make a case on you for murder. You're denying it, but you won't tell us what you were doing at the time. Whatever it was—even if it was illegal—it's a lot less serious than murder. So why don't you save us all a lot of trouble, and spill it?"

He said he'd tell me, but I told him he had to tell the detectives as well. He agreed, and the detectives came back in. What unfolded was a chilling tale indeed: He'd been stalking a woman, preparing to rob her. He described what she did, how she came back from shopping, went in her house, opened the draperies, as he watched from the shrubbery. Something happened to cause him to change his mind, and he left without committing the intended robbery.

Detectives located the woman, asked her what she had done that evening. She had a good memory or a good diary, I don't know which, but her horror as she confirmed everything he said she had done made it clear that he was watching her, not committing murder, the night Jack died.

Some of us continued to believe the suspect guilty, but after that alibi confirmation, we had no case. The suspect himself was murdered, in a poolroom brawl on Christmas Day a couple of years later.

And there the case rested.

By then I was to the point I didn't really care who shot Jack.

All I wished he would do was write me an anonymous letter and tell me

how

he did it.

By anybody's book, that one was impossible. If there was another thing anybody could have done to clear it, I don't know what it was.

But some of yesterday's "impossible" cases would now be very simple. Is this stain really blood? Is it really human blood? What blood type is it? Is it blood from the victim or the assailant? What chemicals are in this body that don't belong there? Are there enough of those chemicals present to be the cause of death?

The Murder of Napoleon

Arsenic and heavy metals do something particularly interesting: They get in the hair. This means that scientists can determine over how long a period this poison was administered, whether it was continuous or stopped and started, and—by means of determining who was always present when it was administered and who was never present when it was administered — determine who did it. There has been one fascinating and unexpected side effect of this research.

For generations, the official dogma has been that Napoleon Bonaparte died of cancer while in English custody on the Island of St. Helena. For generations, many French historians have insisted that the Emperor Napoleon I was poisoned. It is now certain that the French were right. Napoleon Bonaparte died of arsenic poisoning. The brilliant investigative work that led to that conclusion — which included such feats as tracking down and analyzing hair cuttings taken from the body by grieving servants and passed down as family heirlooms—have even implicated a suspect.

I am not a forensic chemist, and in general I do not know how these things work. Even when I have watched the tests given I did not understand what I was watching. But that was all right. What was important to know was not how the tests work but that they do indeed work, so that I would know what to ask for.

Murder or Suicide?

But sometimes nobody can know what to ask for: Sometimes the truth is so bizarre that even after the autopsy and all the detective work have combined to produce it, it remains unbelievable. Such was the case of Mike.

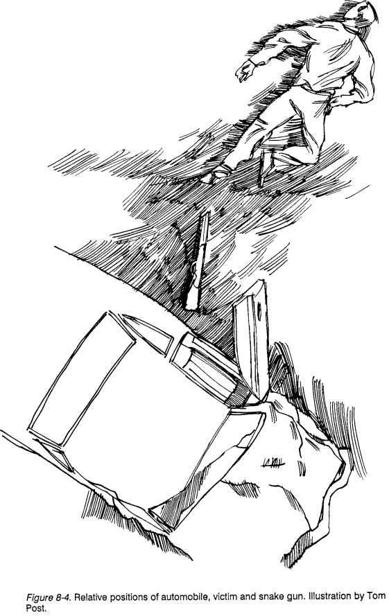

Mike was found dead about two o'clock in the morning near his car, which had plunged off the shoulder of the road, gone into a ditch, and lodged against an embankment so that the passenger's door of the two-door sedan could not be opened. But Mike hadn't died in the wreck. No, he'd died from a single blast from the snake gun—a short, small-gauge shotgun—that lay between him and the car (see Figure 8-4).

We could see where the car had paused on the side of the road, had probably sat there for a while. We could tell that the snake gun had been fired inside the car, that it had hit Mike on the upper-right forehead. We surmised that Mike had paused there with his foot on the brake, without taking the car out of gear, while he and his passenger quarreled; that the passenger shot Mike with the snake gun; that Mike's foot then slipped off the brake and onto the accelerator, causing the car to drive off the shoulder. The passenger, finding himself unable to open his own door, pushed Mike's body out of the way and crawled out, leaving the bloody palm print of his right hand on the driver's door where he had braced himself climbing out.

That left two unanswered questions: Why had the snake gun been tossed outside the car? (We'd expect the suspect to leave it in the car or take it with him.) And why had Mike's body wound up where it did? (That was farther than it had to be moved.)

But if the car wreck had left the suspect a little dazed, both of those questions were at least semianswerable.

Never mind the rest of the night—the lying braggart hearing police at a coffee shop talking about the case, running his own mouth at the bus stop, and sending Johnny Patton, Bob Prickett and me on an all-night chase across three counties. Never mind the next six weeks, while detectives chased down everything they could find and I compared that bloody palm print to the palm print of every known acquaintance of Mike.

And then one night, when I was working 6:00

p.m

. to 2:00

a.m.

and things were quiet, I decided to search the palm print the same way I would search a fingerprint. So what if the FBI said a nonsuspect ident from a palm print was impossible? It certainly would be from their huge files, but we probably didn't have much more than 700 palm prints, and this was a good, clear one containing two good deltas to work from.

So I started searching—and after about four nights of work, I

found the matching print. Only then did I look at the name-and nearly went into shock. I was looking at Mike's own palm print.

But the palm print on the door could not have been made by a body being dragged out. It could only have been made by someone leaning against the door while getting out of the car.

I could hardly wait for the next morning, to call the medical examiner and start asking questions. "Based on your examination, do you think Mike could have lived any period of time after being shot?"