Scene of the Crime

Read Scene of the Crime Online

Authors: Anne Wingate

This is the safe that Jack cracked.

This is the prybar that cracked the safe that Jack cracked.

This is the fingerprint left on the prybar that cracked the safe that Jack cracked.

This is the powder that showed the fingerprint left on the prybar that cracked the safe that Jack cracked.

This is the photo made of the powder that showed the fingerprint left on the prybar that cracked the safe that Jack cracked.

This is the inked print that matched the photo made of the powder that showed the fingerprint left on the prybar that cracked the safe that Jack cracked.

This is the jury that saw the inked print that matched the photo made of the powder that showed the fingerprint left on the prybar that cracked the safe that Jack cracked.

This is the "Guilty!" said by the jury that saw the inked print that matched the photo made of the powder that showed the fingerprint left on the prybar that cracked the safe that Jack cracked.

In real life, we wish it were always that simple.

Sometimes it is. Once I went to a service station burglary. Recognizing the fingerprint (Yes, I know this is theoretically impossible, but I can't help that-sometimes I did it anyway.) on the broken glass as that of a known burglar and forger who had fled town six months before, I asked the owner if he had any checks missing. He told me he didn't.

All too well acquainted with the habits of that particular burglar, I said, "I'm sure you do. Look in the very back of the checkbook."

He did, and to his surprise—but not mine—the last few checks had been torn out. "Seventy-four to detective bureau," I said into my radio. "So-and-so is back in town."

"Thank you," replied Detective Johnny Patton. "En route."

As I went on to other calls, Detectives Patton and Bob Prickett (Yes, these are their real names; I always enjoyed working with them.) hauled the surprised burglar out of his girlfriend's bed, and jailed him before I got back to the police station.

It isn't usually that easy or that fast — and even when it is, it's

easy only because all the homework has been done and all the investigators involved know what they're doing.

In fiction, we want it to be complicated. But no matter how complicated it is, accuracy is important. We're not talking about avoiding that combination of sheer lunacy and total laziness that sometimes turns up in pulp fiction, such as that exhibited by the author who had a security guard in an intelligence agency carrying a

cocked revolver inside

his jumpsuit. Unless the guard had a real yen to sing soprano, he wouldn't.

No, we're talking about the mysteries that could be good and just miss because of inaccuracies. One such mystery—by a brilliant writer—was ruined for me because the author assumed identical triplets would have identical fingerprints. They don't; no identical siblings have identical fingerprints. Another book, by an even more brilliant writer, was similarly ruined because, in the second chapter, the author described a brain as ruby red. I spent the rest of the book waiting expectantly for some exotic poison that would have turned the brain ruby "red. There wasn't one. It turned out to be a simple bashing. Years later, I had a chance to meet that author. When I pointed out to him that the brain is light gray, bearing a distinct resemblance to lumpy oatmeal, he replied ruefully, "Now I know. But I didn't then."

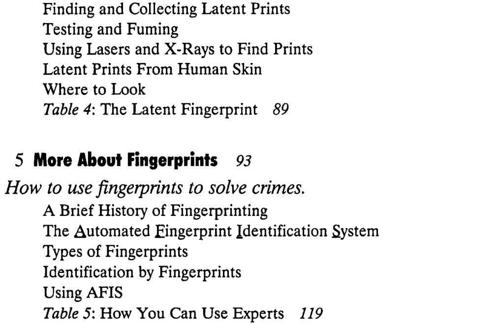

However, that same author had redeemed himself, in my eyes, by writing absolutely the most precise and accurate description of the search for latent fingerprints at a crime scene that I had ever read in any book including my own, and I'm a certified latent fingerprint examiner. I asked him how he'd managed that, and he told me he'd spent two weeks following a fingerprint unit of the New York City Police Department everywhere they went, and asking every question he could think of.

Most of us have neither the time nor the resources to make that kind of an odyssey. We want our work, whether we're writing fictional mysteries or true crime articles or books, to be as accurate as possible. But for most of us, there's no way to know how a crime scene is

really

worked or what

really

happens at the crime lab. We depend on what we read in magazines or glean from books written for specialists.

I spent five and a half years as a police officer attached to the Major Crime Scene Unit in Albany, Georgia (which was then listed as the smallest Standard Metropolitan Area in the United States), and another year as head of the Identification and Crime Scene Unit in Piano, the "Silicon Valley" of Texas. Since then, I've made every effort to keep up with new processes and methods as they have been developed. And here's an example of how things change: When I first began fingerprint work, it was impossible to get the fingerprints of an assailant from the skin of a victim. By the time I left, less than ten years later, there were three methods for doing just that, and I had the equipment for two of them.

At the time I left police work, about twelve years ago, the only way to "search a latent"—that is, compare an unknown latent fingerprint from a crime scene to fingerprints of known criminals, when no suspect has been developed otherwise—was manually. In even a small town, that could take months or even years. I once cleared a robbery exactly one year after it took place, and the month Captain "Doc" Luther and I cleared twenty-four cases, each involving a different criminal, by fingerprints alone, we felt like dancing in the streets. In those days, if the inked prints were filed anywhere other than in the police department that had collected the latent, almost certainly the criminal would never be identified by fingerprints alone. Now this work is done by computer. Local and state files can be searched in minutes, and the vast FBI fingerprint file can be searched in a matter of hours.

When I left police work, genetic fingerprinting did not exist. Now just about everybody has heard of it, and it's turning up in fiction as fast as it is in real life.