Scene of the Crime (6 page)

Read Scene of the Crime Online

Authors: Anne Wingate

Furthermore—and this comes directly from the Constitution's Fourth Amendment, part of the Bill of Rights—the search warrant may be issued only on the basis of probable cause, listing what officers expect to find there and why they expect to find those items, and suspicion isn't probable cause. If an officer saw fifteen known drug wholesalers and twenty known dealers and thirty other people carrying cash and packages entering and leaving a suspect location in twenty minutes, chances are a judge will issue a search warrant. But if all the officer has is the fact that the owner of the house looks scruffy and there has been a lot of coming and going there in the middle of the night, almost certainly a search warrant will not be granted.

In the case of a crime scene, a crime is known to have occurred in that location and officers are looking for all evidence having to do with the crime. Generally, this is sufficient probable cause unless a judge rules otherwise. Judges are highly unpredictable.

The most common basis for issuing a search warrant in a situation not involving an obvious crime scene is the word of an informant. Although courts have ruled that the warrant, and the affidavit given in applying for the warrant, do not have to list the informant's name, the paperwork should specify that this is an informant whose information has in the past proven accurate. (This means that the first time or two that a particular informant is used, there must be some other source of the same information.)

An officer working with an informant should try to get the informant to list as small an item as possible because, remember, the smaller the smallest item listed is, the greater the scope of places the officer may look.

Exceptions to the Rule

There are exceptions to the rule requiring search warrants. If there is strong probable cause and the place to be searched is highly portable—a car, a boat, an airplane—in some situations the officer may reasonably search without a warrant. But if the situation is such that the vehicle can be impounded while a warrant is issued, then the search may not proceed without the warrant. I wrote a novel,

The Eye of Anna,

in which an officer searched a house without a warrant because he had strong probable cause to believe that a murderer had been holed up in the house, a hurricane was in progress, and the officer had reason to believe the house might be blown away before he could finish the search. (It was.) In real life, could he have gotten away with that? Danged if I know, but it was fun to write.

The other main exception is that if an officer has grounds to fear for his/her own personal safety, s/he may immediately search any area within the immediate physical control of the suspect for weapons. Often, officers stopping a car and searching the glove box under this exception find drugs instead of a weapon. Almost invariably, an immediate court battle ensues, arguing whether the officer had actual and reasonable cause to search for a weapon or whether the search for the weapon was merely an excuse to search for drugs. Courts have ruled differently in different situations, so this is a wide-open area to consider in writing fiction.

In real life, it is essential that no officer conduct a search alone. There should always be at least two people to testify as to what was found and who found it. Furthermore, the two people must always search together; it won't do any good, later in court, for Mel to testify that s/he was there when N.E. Boddy found the murder weapon, if Mel was outside or in another room and Boddy is accused of planting the weapon.

But this isn't a law book. Let's get on to what your character might find, how s/he should treat it and not treat it at the scene, and what can be done with it later in the lab. Always, always, always, remember that this information changes fast, so check with your real jurisdiction, or the closest real one to a fictitious one, at the time you are writing as to what can be done there at that time.

Identification and crime-scene officers are genial souls, almost always happy to tell you what they're doing and show you around, provided they don't have a call at the moment. (But do be aware that even if you have an appointment, you can't count on the officer being there. Crime takes precedence.)

Evidence Collection

For now, let's get on with evidence collection. How do officers collect different items of evidence? What do they do with them after collecting them? In this chapter, we'll discuss collecting and packaging the evidence. In chapter nine, we'll examine what the lab does with the evidence.

Expect the Unexpected

The only way an evidence technician can be prepared for anything is to be prepared for everything. Murder happens fast.

At the very least, an evidence collection kit must contain large, medium and small paper and plastic bags. If they are not preprinted with evidence tags (we'll get to those later), evidence tags can be attached with string or tape. The kit must contain paper coin envelopes, small vials of the type used by pharmacies to dispense tablets, and larger plastic or glass containers with airtight lids. Anything meant to contain liquids should be made of an inert material, so that the eyedropper and/or container will not leave its own chemical trace in the liquid, unless of course the lab already knows about and plans for the chemical trace, as in the case of some prepackaged kits. There should be a supply of cardboard boxes that can be set up to hold larger items; prepackaged kits for gunpowder residue, blood samples and rape analysis; vials with disposable eyedroppers fixed in the lids; dental casting material and equipment (the same stuff the dentist used to get the exact shape your bridge needed to be), and plaster casting material and equipment. Tweezers and scissors are essential. Obviously, the kit must contain evidence tags and the long, yellow preprinted evidence tape to keep people out of the immediate crime scene (although it's usually necessary, if it's a major crime, to post a few patrol officers on the perimeter also).

Rubber gloves are critical; I once caught pneumococcal pneumonia from a corpse, and in this day of AIDS, anybody who handles bloody items without wearing gloves is clearly suicidal.

Of course you already know your character will need notebook, pens, pencils, tape measures, a camera and strobe, and plenty of film and batteries.

It is useful to have several heavy-duty cardboard boxes with pegboard bases, and a number of long, heavy nails to put through the bottom of the pegboard, so that oddly-shaped items may be securely immobilized.

This kit should be kept at all times in the vehicle that will be used. Each time the kit is used it must be

immediately

restocked, to be ready for its next use. Obviously, if the vehicle must go into the shop, the kit must be moved to the substitute vehicle. Murder happens fast and it doesn't give the unprepared person time to say "Oops, let me get my stuff together." An officer who isn't prepared to go with no advance warning whatever and spend the next ten hours working a major crime scene, photographing, measuring, charting and collecting upwards of 500 pieces of numbered and labeled evidence, without sending a patrol officer out to an all-night drugstore to get something s/he forgot, isn't prepared at all.

That doesn't mean your fictional character really has to be that well prepared. Sometimes a lack of preparation may add to the drama of the story—but remember that it also must be consistent with your character or story line. Either the character is perennially forgetful or lazy (like Joyce Porter's Dover), or the character has just finished with one major crime and is too dog-tired to remember to restock instantly.

Each Item Packaged Separately

When collecting evidence, the technician must package each item separately. This includes, for example, putting each shoe in a separate labeled evidence bag if a pair of shoes is being collected. If a victim's clothing is being collected, each item of clothing goes in a separate bag. (Yes, that includes each sock. It is appropriate to handle them with tweezers.) It is critical to label each item the moment it is collected, and to make corresponding notes in the technician's notebook immediately. Trusting it to memory and planning to write it up later is extremely stupid; memory cannot be trusted that far, especially by someone who has other things on his/her mind.

Paper or Plastic?

How does your character decide whether to use paper or plastic to collect the evidence?

If the item is likely to be even slightly damp, it must be packaged in paper so that the moisture can continue to evaporate; otherwise, the item is likely to begin to rot. Clothing with blood on it is a special problem. It should not be folded in on itself; rather, it must be spread out and allowed to dry. In Albany, Georgia, where I worked for nearly seven years, this was a big problem for a long time; there were times when we had no usable interrogation rooms because they all were full of bloody clothing drying out. (And one rather hysterical day, one detective ushered a suspect into an interrogation room another detective had just put a suspect shotgun in. Fortunately, the suspect was a rather mild-mannered burglar, and on seeing the shotgun he backed out in a hurry.)

But we had one unexpected and somewhat serendipitous stroke of luck. One day a city commissioner walked through the city parking garage and saw Doc Luther, head of the crime-scene unit, and me fingerprinting a suspect vehicle. He stopped short. "Don't you have a better place to do that?" he demanded.

"No, sir, we do not," Doc told him. "Not unless we want to do it outside." (The day was rainy. Fingerprint powder and rain do not combine well.)

The commissioner asked more questions, and Doc let him have the situation: We had already lost one case in court because we were fingerprinting a car full of stolen property when the suspect walked by. Although in fact the suspect did not touch any of the stolen property at that time, he managed to convince a jury that he did and that was how his fingerprints got there. Even Doc and I had to admit that the suspect had been close enough that he

could

have touched the property. He mentioned the problem with bloody clothing— which should have been our responsibility, but we had no place to deal with it—drying in interrogation rooms. He explained that the problems were getting worse, as crime in the city expanded at a geometric rate.

"I'll take care of that," the commissioner said.

A few months later, we had a nice building at the bottom of the parking lot. It was big enough for us to fingerprint even a large suspect vehicle and to process and store other large evidence. From then on, bloody clothing was dried and stored there.

If your officer is working in a small jurisdiction, by all means use the problems of small departments. Things can't be done exactly right, and there are tremendous fictional opportunities there.

Nothing with blood on it should ever be packaged in plastic or glass or anything else airtight, unless it is the blood itself and it is put in special vials that already contain a known blood preservative. The laboratories can work easily with dried blood or with properly preserved blood, but not with rotted blood.

Dry items may be packaged in plastic, although no particular harm is done if they are packaged in paper. Something that may need to be repeatedly examined, such as a pistol, should always be in transparent plastic, so that it can be examined without the police seal being broken. Obviously, any time the seal is broken—for fingerprinting or test-firing—notations should be made on the evidence tag, so that the defense attorney can't question later why there are two or three sets of staple holes.

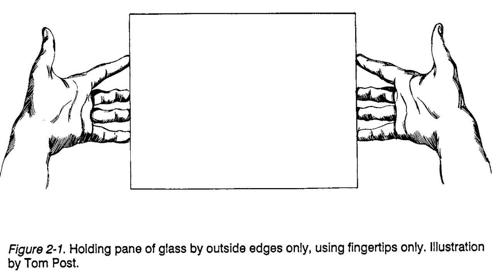

Learning to pick things up without damaging fingerprints that might be on them is an art. It generally involves using only the fingertips to pick up items and holding them by edges that are too small to hold prints (see Figure 2-1); there is really no way to learn without practicing. Try it yourself, so as to know the problems your character is facing.

Let's go on, now, talking for a few paragraphs as if you are your character.

Once you have succeeded in picking up the item, the next problem is packaging it without rubbing out the fingerprints. If the item is absorbent, there is no problem at all. Those prints aren't going anywhere. They are in the substance, not just on the surface, of the item. However, you must be extremely careful not to touch the items yourself, as even the most casual touch will add more prints. These things are best handled with tweezers at all times.

If the item is irregularly shaped, there's really little problem, because the protrusions will hold the paper or plastic away from the rest of the surface and keep it from rubbing out prints. But when you have something regularly shaped—a drinking glass, a pane of glass—you may have problems, because plastic will tend to mold around the item and rub out prints. Paper works better, especially ordinary brown paper grocery-type sacks, because they are too stiff to rub out prints unless the item is badly mishandled. In actual practice, Doc and I tended to print small items on the scene whenever possible, and then transport them (if necessary—often the prints were all we needed, and the item could be left at the scene) with fingerprints already protected by tape. With larger, heavier