Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness (79 page)

Read Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness Online

Authors: Anne Waugh,Allison Grant

Tags: #Medical, #Nursing, #General, #Anatomy

outline the causes and effects of dementia

relate the pathology of Parkinson’s disease to its effects on body function.

Increased intracranial pressure

This is a serious complication of many conditions that affect the brain. The cranium forms a rigid cavity enclosing: the brain, the cerebral blood vessels and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). An increase in volume of any one of these will lead to raised intracranial pressure (ICP).

Sometimes its effects are more serious than the condition causing it, e.g. by disrupting the blood supply or distorting the shape of the brain, especially if the ICP rises rapidly. A slow rise in ICP allows time for compensatory adjustment to be made, i.e. a slight reduction in the volume of circulating blood and of CSF. The slower the rise in ICP, the more effective is the compensation.

Rising ICP is accompanied by bradycardia and hypertension. As it reaches its limit a further small increase in pressure is followed by a sudden and usually serious reduction in the cerebral blood flow as autoregulation fails. The result is hypoxia and a rise in carbon dioxide levels, causing arteriolar dilation, which further increases ICP. This leads to progressive loss of functioning neurones, which exacerbates bradycardia and hypertension. Further cerebral hypoxia causes

vasomotor paralysis

and death.

The causes of increased ICP are described on the following pages and include:

•

cerebral oedema

•

hydrocephalus, the accumulation of excess CSF

•

expanding lesions inside the skull, also known as space-occupying lesions

–

haemorrhage, haematoma (traumatic or spontaneous)

–

tumours (primary or secondary).

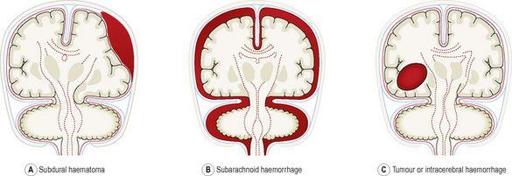

Expanding lesions may occur in the brain or in the meninges and they can damage the brain in various ways (

Fig. 7.49

).

Figure 7.49

Effects of different types of expanding lesions inside the skull: A.

Subdural haematoma.

B.

Subarachnoid haemorrhage.

C.

Tumour or intracerebral haemorrhage.

Effects of increased ICP

Displacement of the brain

Lesions causing displacement are usually one sided but may affect both sides. Such lesions may cause:

•

herniation

(displacement of part of the brain from its usual compartment) of the cerebral hemisphere between the corpus callosum and the free border of the falx cerebri on the same side

•

herniation of the midbrain between the pons and the free border of the tentorium cerebelli on the same side

•

compression of the subarachnoid space and flattening of the cerebral convolutions

•

distortion of the shape of the ventricles and their ducts

•

herniation of the cerebellum through the foramen magnum

•

protrusion of the medulla oblongata through the foramen magnum (‘

coning

’).

Obstruction of the flow of cerebrospinal fluid

The ventricles or their ducts may be pushed out of position or a duct obstructed. The effects depend on the position of the lesion, e.g. compression of the aqueduct of the midbrain causes dilation of the lateral ventricles and the third ventricle, further increasing the ICP.

Vascular damage

There may be stretching or compression of blood vessels, causing:

•

haemorrhage when stretched blood vessels rupture

•

ischaemia and infarction due to compression of blood vessels

•

papilloedema

(oedema round the optic disc) due to compression of the retinal vein in the optic nerve sheath where it crosses the subarachnoid space.

Neural damage

The vital centres in the medulla oblongata may be damaged when the increased ICP causes ‘

coning

’. Stretching may damage cranial nerves, especially the oculomotor (III) and the abducent (VI), causing disturbances of eye movement and accommodation.

Bone changes

Prolonged increase of ICP causes bony changes, e.g.:

•

erosion, especially of the sphenoid

•

stretching and thinning before ossification is complete.

Cerebral oedema

There is movement of fluid from its normal compartment when oedema develops (

p. 117

). Cerebral oedema occurs when there is excess fluid in brain cells and/or in the interstitial spaces, causing increased intracranial pressure. It is associated with:

•

traumatic injury

•

haemorrhage

•

infections, abscesses

•

hypoxia, local ischaemia or infarcts

•

tumours

•

inflammation of the brain or meninges

•

hypoglycaemia (

p. 228

).

Hydrocephalus

In this condition the volume of CSF is abnormally high and is usually accompanied by increased ICP. An obstruction to CSF flow (see

Fig. 7.17

) is the most common cause. It is described as

communicating

when there is free flow of CSF from the ventricular system to the subarachnoid space and

non-communicating

when there is not, i.e. there is obstruction in the system of ventricles, foramina or ducts.

Enlargement of the head occurs in children when ossification of the cranial bones is incomplete but, in spite of this, the ventricles dilate and cause stretching and thinning of the brain. After ossification is complete, hydrocephalus leads to a marked increase in ICP and destruction of nervous tissue.

Primary hydrocephalus

In this condition there is accumulation of CSF accompanied by dilation of the ventricles. It is usually caused by obstruction to the flow of CSF but is occasionally due to malabsorption of CSF by the arachnoid villi. It may be communicating or non-communicating. Without treatment, permanent brain damage occurs.

Congenital primary hydrocephalus

is due to malformation of the ventricles, foramina or ducts, usually at a narrow point.

Acquired primary hydrocephalus

is caused by lesions that obstruct the circulation of the CSF, usually expanding lesions, e.g. tumours, haematomas or adhesions between arachnoid and pia maters, following meningitis.

Secondary hydrocephalus

Compensatory increases in the amount of CSF and ventricle capacity occur when there is atrophy of brain tissue, e.g. in dementia and following cerebral infarcts. There may not be a rise in ICP.

Head injuries

Damage to the brain may be serious even when there is no outward sign of injury. At the site of injury there may be:

•

a scalp wound, with haemorrhage between scalp and skull bones

•

damage to the underlying meninges and/or brain with local haemorrhage inside the skull

•

a depressed skull fracture, causing local damage to the underlying meninges and brain tissue

•

temporal bone fracture, creating an opening between the middle ear and the meninges

•

fracture involving the air sinuses of the sphenoid, ethmoid or frontal bones, making an opening between the nose and the meninges.

Acceleration–deceleration injuries

Because the brain floats relatively freely in ‘a cushion’ of CSF, sudden acceleration or deceleration has an inertia effect, i.e. there is delay between the movement of the head and the corresponding movement of the brain. During this period the brain may be compressed and damaged at the site of impact. In

‘contre coup’

injuries, brain damage is more severe on the side opposite to the site of impact. Other injuries include:

•

nerve cell damage, usually to the frontal and parietal lobes, due to movement of the brain over the rough surface of bones of the base of the skull

•

nerve fibre damage due to stretching, especially following rotational movement

•

haemorrhage due to rupture of blood vessels in the subarachnoid space on the side opposite the impact or more diffuse small haemorrhages, following rotational movement.

Complications of head injury

If the individual survives the immediate effects, complications may develop hours or days later. Sometimes they are the first indication of serious damage caused by a seemingly trivial injury. Their effects may be to increase ICP, damage brain tissue or provide a route of entry for microbes.

Traumatic intracranial haemorrhage

Haemorrhage may occur causing secondary brain damage at the site of injury, on the opposite side of the brain or diffusely throughout the brain. If bleeding continues, the expanding haematoma increases the ICP, compressing the brain.

Extradural haemorrhage

This may follow a direct blow that may or may not cause a fracture. The individual may recover quickly and indications of increased ICP appear only several hours later as the haematoma grows and the outer layer of dura mater (periosteum) is stripped off the bone. The haematoma grows rapidly when arterial blood vessels are damaged. In children there is rarely a fracture because the skull bones are still soft and the joints have not fused. The haematoma usually remains localised.