Resolute (12 page)

Authors: Martin W. Sandler

British technological advances would allow Barrow to send out ships that would be marvels of their age. All of the new expedition's officers and crew would be handpicked. Butâand it was a vital concernâwhom should he trust to command his largest and most important expedition?

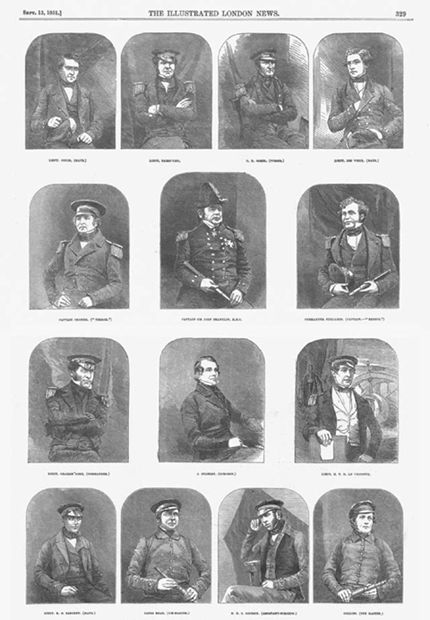

Parry, who was still Barrow's favorite, was his first choice. But after three expeditions, Parry had had enough of the Arctic, and he politely refused. The next choice was James Clark Ross, who had recently returned from a South Pole-seeking expedition. Although he had not made the Pole, he had had planted the English flag further south than any explorer had previously traveled. But Ross had recently married and had promised his new wife that his days in the Arctic were over. Because Barrow was planning to rely on steam power to assure the expedition's success, his third choice was Commander James Fitzjames who, while lacking any Arctic experience, had worked successfully with steam engines. But the Admiralty turned Fitzjames's appointment down. He was, they told Barrow, simply too young to command so vital an enterprise. George Back was also a contender, but despite the heroics he had displayed during John Franklin's first overland expedition, Barrow felt Back was too argumentative to lead such an important expedition. Captain Francis Crozier also seemed a logical choice. He had made five successful Arctic voyages and had served James Clark Ross well as second-in-command on his Antarctic achievement. But once again naval upper-class snobbery held sway: Crozier was not only common-born, but Irish. He would never do.

Barrow was stuck. His final and most ambitious searchâand he had no one to lead it. He knew that he had to have a recognizable figure, someone who would engender support from both the public and the press. Reluctantly, he had to admit that he had only one choice left, a person he didn't really want. It was John Franklin.

Franklin had led a varied career since returning from the overland expedition that had almost killed him. In 1823, he had married poet Eleanor Porden, who had given him a daughter, Eleanor. Two years after the marriage, when Franklin was offered a second overland search, his wife lay dying of tuberculosis. Despite her illness, she urged Franklin to accept the opportunity, and off he went. She died six days after his departure.

The second overland journey was far better organized than the first had been. With Dr. John Richardson (who had served as the naturalist on Franklin's first overland expedition) as second-in-command, the party traveled overland more than two thousand miles and successfully charted an area comprising half the Arctic coast of Canada and a large portion of the Alaskan seaboard. Under Richardson's guidance, the expedition recorded important meteorological and geological information and made notes of more than 663 plants.

Franklin returned to England in 1827 and a year later he married a friend of Eleanor's, thirty-six-year-old Jane Griffin. Together they spent the next six years in the Mediterranean, where Franklin had been assigned to oversee Greece's transition to an independent nation. For Franklin, it was a matter of biding his time, waiting for the next Arctic assignment. Surely it would come. His second Canadian venture had been an unqualified success. And he was now

Sir

John Franklin, knighted by George IV for his accomplishments.

But he did not get the call. Returning to England in 1834, he had petitioned for the next passage-seeking assignment. It went to George Back. Two years later, he was appointed Governor of Van Diemen's Land (present-day Tasmania). It would be a horrendous experience. Van Diemen's Land was a prison colony, the home of eighteen thousand of England's most hardened criminals. It had been long controlled by upper-class colonial officers who lived a life of luxury by profiting handsomely from the convicts' labor.

Determined to make the best of the situation, Franklin, at the strong urging of his wife, attempted to institute a series of reforms, chiefly aimed at providing more humane treatment for prisoners. He was opposed every step of the way by the colonial officials, who were accustomed to having their governor join in on the profit-taking. True to his character, Franklin spent seven agonizing years attempting to overcome the opposition. But the man who had repeatedly faced death in pitched naval engagements and the Arctic wilderness was no match for the political machinations of those whose way of life he threatened. In 1843, they succeeded in having Franklin recalled.

It was the lowest point in his life. He was almost sixty years old; he had been removed from the search for the passage for almost twenty years, and he had returned to England an administrative failure. What he didn't know was that, largely by default, he was about to be given the most prized assignment of them all.

As he approached the painful conclusion that Franklin was emerging as his only option, Barrow was deeply torn. No one was more aware of Sir John's strengths and weaknesses. It was Barrow, after all, who had entrusted the man with three of his earliest missions. On the downside, Franklin had taken part in the Buchan failure. He had lost eleven men on the Coppermine search. His experience in Van Diemen's Land had been a disaster. Physically, he was still plump and out of shape. Moreover, he was old for such an assignment. And he had not been in the Arctic for more than sixteen years.

It was not that Franklin was without considerable strengths. In both combat and his previous Arctic experiences he had demonstrated remarkable courage. He was an excellent seaman. He was genuinely liked, even admired, by those who served under him. He was unflaggingly loyal and he had again proved in both his overland expeditions that he was dogged, particularly in his determination to follow whatever orders he was given.

In the end, however, it was none of these qualities that got Franklin his commandâaside from the default factor, it was his petite, elegant, and highly intelligent wife who was the catalyst. Lady Jane Franklin was one of the most remarkable females of her era. She would eventually become the most influential woman in all of Arctic exploration.

Born in London in 1791, Jane Franklin defied every taboo of her day. Rather than devote herself to the genteel domestic life dictated by society, she became a social activist who took a backseat to no one in expressing her opinions on any matter. Endowed with boundless energy, she visited prisons, sat in on lectures at the Royal Institution, and attended meetings of the British and Foreign School Society. Before marrying Franklin, she had traveled widely with her father to a number of foreign countries where she meticulously recorded her impressions of every landmark she visited. Those who knew her well were particularly impressed with her thirst for knowledgeâduring one three-year period she had read 295 books, delving into issues ranging from social problems to education and religion.

Most of all, Jane Franklin was a woman determined to get what she wanted, and more than anything else, she wanted to get for her husband what she believed he deserved. And ultimately, that meant helping him to gain the greatest honor of allâto be forever known as the discover of the Northwest Passage. She would simply not sit idly by while he, the naval hero, the man who had eaten his boots, the man who had charted much of the Arctic coast, was being denied his moment of glory.

She loved her husband dearly, but she felt thatâlacking her own aggressive natureâhe needed to be reminded of what, despite his setbacks, had elevated him to the esteem in which he was held by the British public. “The character and position you possess in society,” she confided to him, “and the interestâI may say celebrityâattached to your name, belong to the expeditions and would never have been acquired in the ordinary line of your [naval] profession ⦠You must not think I undervalue your military career. I feel it is not that, but the other, which has made you what you are.”

But for Jane Franklin, simply reminding her husband of his destiny was not enough. Action had to be taken. While Barrow debated with himself over Franklin's selection, Lady Jane began to campaign relentlessly on his behalf. No influential body escaped her lobbyingâthe navy's Arctic Council, the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty, members of Parliament, the officers of the Royal and Geographical Societies. Aware that James Clark Ross had been one of Barrow's prime candidates, and concerned that he might change his mind and accept the command, she even wrote to him, stating, “If you do not go, I should wish Sir John to have it⦠and not be put aside by his age⦠I think he will be deeply sensitive if his own department should neglect himâ¦I dread exceedingly the effect on his mind.”

By the time her petitioning was through, each of these bodies was convinced that John Franklin was their man. Given the absence of other notable candidates, Sir John would have received the command in any case. But any lingering doubt was effectively removed by what Lady Franklin had managed to accomplish. It would not be the last time that her indomitability and will would influence naval events.

Now that he had decided, Barrow was equally determined. The choice was Franklin, weaknesses and all. But everything possible would be done to make certain that he succeeded. Above all, that meant sending him out in the strongest, most technologically advanced, and best supplied ships that had ever entered the Arctic.

They were the

Erebus

and the

Terror

, the two most famous and celebrated vessels in Great Britain. Only two years earlier they had returned from successfully carrying James Clark Ross and his men to the Antarctic. The

Terror

was particularly renowned. Stories still circulated throughout the country of how, after being tossed and battered among the ice floes for the better part of 1836, it had held together long enough for George Back to escape with his life. Two decades earlier, it had been the

Terror

that had fired the shots on Fort McHenry, which had led to that irritating song the Americans had adopted as their national anthem.

The

Erebus

and the

Terror

were what the navy called bomb ships, designed to bombard enemy shore batteries. Constructed of English oak, they were built to be strong enough to accommodate the weight and recoil of multi-ton mortars, and hundreds of pounds of shells and explosives. The

Erebus

, the largest vessel Barrow had sent to the Arctic, weighed 372 tons, was 105 feet long, and had a 29-foot beam. The

Terror

weighed 326 tons, was 102 feet long, and had a 27-foot beam.

Both ships had been extensively refitted to make certain they could withstand the pressure of even the thickest ice packs. Their bows were reinforced inside with a maze of beams, eight feet thick in all, and outside with inch-thick plates of iron. Five layers of African oak, English oak, and Canadian elm were added to the vessel's sides, which were also raised to keep ice from cascading over them. The decks and the bottoms of the ships were also heavily reinforcedâan additional three inches of fir planking laid on the decks and seven layers of solid oak added to the bottoms.

Unlike any ships before them, the

Erebus

and the

Terror

were each also fitted with an internal heating system to protect against the cold. Huge pipes installed around the lower deck of each vessel carried steam provided by tubular boilers and supplied heat to the officers' cabins and the crew's living quarters. As a further precaution against subzero temperatures, double doors were added to all hatches and ladderways.

The most dramatic improvements, however, were in the way the ships were to be powered and propelled. Determined that they were to be independent of the wind and able to force their way through any conditions the ice might present, Barrow had the

Erebus

fitted with a fifteen-ton, twenty-five-horsepower locomotive engine. The

Terror

was equipped with a slightly smaller engine. Then he went a step further. Rather than paddle wheels, which, although they were the standard means of propulsion on steam vessels, were particularly vulnerable to ice, the

Erebus

and the

Terror

were equipped with screw propellers, which promised to be far better able to handle the batterings of ice and storm. Still not content, Barrow had engineers design the propellers in such a way that they, like the ships' rudders, were retractable, capable of being hoisted out of harm's way if their destruction by ice seemed imminent.

Finally, in case of the unlikely event of a calamity, Barrow saw to the lifeboats. Each vessel would be supplied with enough boats to carry all of its crew if the ship was destroyed or had to be abandoned. When his improvements were completed, Barrow was convinced that he had done what he had to do. Franklin's one task would be to find the passage. His ships would carry him through.

Barrow also made sure that the

Erebus

and the

Terror

were the most extravagantly provisioned vessels that had ever headed for the Arctic, carrying enough food and other supplies to last for a minimum of three years, and as many five if conditions demanded it. The supplies included 7 tons of flour, 4,500 gallons of alcohol, and almost 4 tons of tobacco. And, like the technological improvements, the nature of the food provisions was revolutionary as well. Barrow had also decided to take advantage of another recent inventionâthe tin container. Packed aboard the

Erebus

and

Terror

were over 8,000 cans containing 15 tons of a variety of meats, 9 tons of canned vegetables, and 12 tons of different kinds of canned soups. To protect against scurvy, more than 30 barrels of lemon juice were loaded aboard. In addition to all these essentials, the ships were equipped with hand organs, mahogany writing desks, and libraries totaling some 3,000 books.