Resolute (16 page)

Authors: Martin W. Sandler

THIS MAP SHOWS

the major events in the dramatic voyage of the HMS

Investigator:

The route that Robert McClure took in finding the last link in the Northwest Passage, the site where his ship became entrapped, and the spot from which members of the

Resolute

launched the sledging party that resulted in the rescue of McClure and his crew.

The storm was over and the

Investigator

was totally covered and surrounded by ice. But McClure had only one thing on his mind: He had to be even more certain that what his lookout had spotted was correct. Leaving the

Investigator

, he led a sledge party across the ice to the land on the east side of the waterway. Then, with the ship's doctor, Alexander Armstrong, and a few of his men, he climbed a fifteen-hundred-foot mountain and from that height spied the end of the ice-filled channel (which he had earlier named Prince of Wales Strait) and the open water beyond. “The highway to England from ocean to ocean lay before us,” Dr. Armstrong would later write.

It was still not good enough for McClure. Nothing would do but actually standing on the shore of the passage. Eleven days later he led another sledge party along the eastern shore of Banks Land to the end of the channel. There, on October 26, 1850, Robert McClure, standing on a six-hundred-foot hill, became the first man to ascertain that there was indeed a water route from the Atlantic to the Pacific. The more than four-hundred-year-old dream was real; the Northwest Passage existedâand it had been found. In words that would have gladdened the heart of John Barrow, Dr. Armstrong would later describe the emotions he felt as he realized that “the maritime greatness and glory of our country were still further elevated above all nations of the earth.”

Returning to the

Investigator

, McClure informed the crew that, with the passage found, they could claim the £20,000 prize. Their joy was tempered, however, by the realization that they would have to spend the winter in the unprotected middle of Prince of Wales Strait. Yet again, luck was with them. Although the season was bitterly cold, no storms rivaling those they had experienced the year before struck the ship and in the early spring, before the ice released them, McClure sent out three long sledge expeditions in search of Franklin. All returned with nothing to report.

Six weeks later the ice broke up. At this point many in the crew were anxious to return home. They had had enough of cheating disaster. And although they had not found Franklin, they knew they would be returning to a heroes' welcome. But McClure had another agenda. It was not enough to have proved the existence of the passage. He had to sail through it.

He almost made it. He was less than sixty miles from sailing through Prince of Wales Strait when once again he found the final stretch of the channel frozen over. He still wouldn't give up. Turning around, he made his way back up the strait and began looking around for another channel that might lead him into the open sea. He found one that looked promising and sailed three hundred miles down it before it became so narrow and icebound that he was forced to halt.

Once again McClure had led his men into a life-threatening situation. As the tide mounted, huge blocks of ice slammed against the

Investigator

, threatening to sink it. For the second time in the voyage, McClure was ready to abandon ship and, for the second time, just as he was about to do so, the weather changed and the ice became motionless. McClure had still not run out of miracles.

It was time to find another winter haven. Escaping the channel, he sailed south for the better part of a month looking for a protected spot. Finally he found one and named it Mercy Bay. Later, Dr. Armstrong remarked upon the name, stating that “some of us not inappropriately said it ought to have been so-called, from the fact that it would have been a mercy had we never entered it. He was right. McClure had unwittingly chosen a bay in which the tides were such that the waters leading out of it remained frozen all year long. McClure and his men would be trapped in Mercy Bay for two years. The

Investigator

would never be released, and the officers and crew that had finally found the Northwest Passage would come within days of starving to death.

CHAPTER 9.

CHAPTER 9.The Arctic Traffic Jam

“Graves, Captain Penny, graves!”

âSailor from the

WILLIAM PENNY

RESCUE EXPEDITION

, 1850

T

HE SELECTION OF RICHARD COLLINSON

and Robert McClure to command the first of the many 1850 rescue expeditions had engendered little surprise. Both were respected, seasoned naval veterans, accustomed to navy discipline, traditions, and ways of doing things. The man who led the expedition sent out some four months after Collinson and McClure, however, was a most unlikely choice. The selection of William Penny was perhaps the greatest indication of how concerned both the Admiralty and the Arctic Council had become over Franklin's fate and how much these two bodies were being pressured to do everything that could be done to find him.

Penny was not a navy man. He was, of all things, a whaler, the very sort that the navy had assiduously refused to put in command of any of its ships. Not that the navy did not recognize Penny's skills and knowledge; now forty-one, Pennyâwho was regarded by those who had sailed under him as both humorless and overly ambitiousâhad been a master of whaling vessels for sixteen years and had been sailing the Arctic waters since the age of eleven. It had, in fact, been he who, guided by an Inuit whom he had all but adopted, had discovered the whaling grounds at the mouth of Cumberland Sound, an area that would prove to be one of the most fertile of all places in which to hunt the baleen-rich bowhead whale. For years the navy had sought Penny's advice about Arctic topography and conditions, but giving him command of two Royal Navy vessels? Only a year ago it would have been unthinkable.

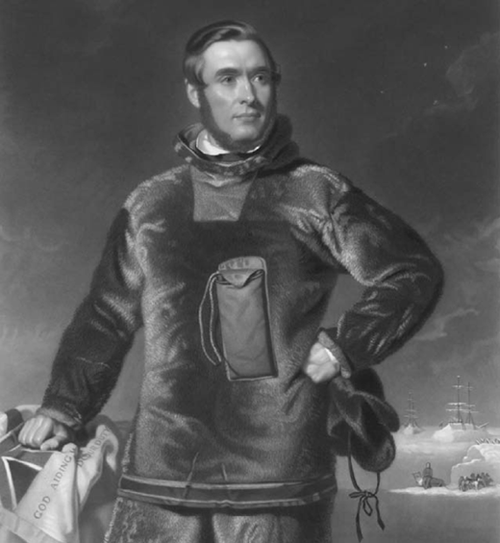

HE WAS A WHALEMAN

, not a British naval officer. But it would be William Penny who would prove to be one of the most determined of all the Franklin seekers.

What really changed the Admiralty's position? Again it was Jane Franklin. Even before the Collinson-McClure expedition had been organized, she had begun making plans to mount her own private rescue mission. And she had asked William Penny, described by one of his shipmates as “vigorous and full of energy and zeal in the Franklin cause,” to command it. Penny not only accepted but stated that he expected no compensation for undertaking such a “humanitarian mission.” Lady Franklin then launched yet another lobbying campaign aimed at persuading the Admiralty to finance the expedition. As always, she made sure that the press was well aware of both her petitions and the fact that, if the navy refused to underwrite the search, she was prepared to use her dwindling funds to do so herself. As she expected, editorials and letters from readers began appearing, decrying the fact that this “brave woman” (now nothing less than a national heroine) was about to risk poverty to save her husband and his noble companions. The Admiralty was forced to give in; it would supply Penny with two naval vessels and would finance the mission. Once again, Jane Franklin had shamed the navy into bending to her will.

Penny sailed from England on April 13, 1850, with two relatively small vessels appropriately named

Lady Franklin

and

Sophia

(Jane and Sir John's favorite niece). He carried with him a letter from Lady Franklin to be delivered to her husband, should Penny find him. “I desire nothing,” she had written, “but to cherish the remainder of your days, however injured and broken your health may beâ¦I live in you my dearest⦠I pray for you at all hours.” Exactly one week after Penny departed, another rescue expedition left in its wake. Its commander was seventy-three years old, his ships were private yachts, and he had raised the money for the search largely through public subscription. It was none other than John Ross, determined to keep his promise that, if necessary, he would rescue his friend. As he once again headed for the Arctic, John Ross, the oldest commander in the British navy, was convinced he would do just that.

Given his past history, the navy did not share Ross's confidence in the success of his private search. But it had great hopes for the man chosen to lead the fourth expedition sent out in 1850. A veteran of the War of 1812, where he had demonstrated great courage during the attacks on Washington, Baltimore, and New Orleans, the crusty, opinionated Horatio Austin was, at forty-nine, regarded by both the Admiralty and the Arctic Council as one of the navy's shining stars. The son of a Chatham dockyard official, he had gained his first Arctic experience while serving as a lieutenant aboard the ill-fated

Fury

during Edward Parry's third search for the passage. Promoted to captain, he had commanded the HMS

Cyclops

during the Syrian War of 1839â40, during which he had again been cited for skill and bravery under fire. He had then spent more than two years conducting research on the development of naval steam vessels.

Now he'd been given command of the largest and most ambitious expedition ever sent to the Arctic. His flagship was the HMS

Resolute

, a massively built 424-ton vessel, 115 feet long with a 28 1/2-foot beam. More than any of the other ships in Austin's fleet, the

Resolute

was constructed for Arctic duty. Its bow and decks were built up with three thicknesses of wood to withstand the pressure of the ice and all of its decks were double planked. The furnace-fed steam pipe, which passed under every sleeping berth and through every cabin, was designed to keep the vessel warm even when the outside temperature plummeted to as low as seventy degrees below zero. The rest of Austin's fleet consisted of the

Assistance

, commanded by Captain Erasmus Ommanney; the

Pioneer

, led by Lieutenant Sherard Osborn; and the

Intrepid

, commanded by John Bertie Cator.

Four great navy ships, led by four proven navy men. Nothing had yet been heard from either Collinson or McClure. Perhaps there would soon be encouraging news from them. If not, then surely, the Admiralty believed, it would be Austin who would finally find Franklin or at least evidence of what had happened to him.

Jane Franklin, on the other hand, was still not satisfied. Yes, the navy had, at last, truly committed itself to finding her husband. But now she had another concern: What if all these recently departed expeditions were looking in the wrong places? She had talked with every one of the commanders who had gone looking for the passage. She had met with John Richardson and James Clark Ross almost as soon as they had returned. She had pored through every report and published account that these seekers had written. And she had studied every new map of the North that had been drawn. At this point, no one knew more about the Arctic than she.

Now, as she read and reread the orders that Penny and Austin had been given and considered the areas in which John Ross intended to search, she became increasingly troubled. Based on the report they had been given that all the passageways leading south were blocked, they were all focusing their attention on the far north. No one was looking along the coast to the south. According to his orders, that was where Franklin was supposed to go. And, as Lady Franklin knew better than anyone else, if those were his orders, her husband would do everything in his power to carry them out.

As usual, Jane Franklin acted upon her concerns. Since the navy was not sending anyone to look to the south, she would take care of that herself. Convincing a friend to lend her his ninety-ton former pilot boat, the

Prince Albert

, she outfitted the vessel by contributing yet more of her own funds and by raising the remainder of what was needed from other friends. To command the mission she chose Lieutenant Charles Codrington Forsyth, a man whom she had met and befriended while living in Van Diemen's Land. Although Forsyth had never been to the Arctic, he shared Lady Jane's conviction that Sir John would be found by searching to the south.