Resolute (8 page)

Authors: Martin W. Sandler

By July 14, they had managed to paddle far enough down the rock- and rapids-filled Coppermine for Dr. Richardson to climb a hill where he spotted the Arctic Ocean. A few days later, they reached the river's mouth and the coast. Franklin was determined to begin exploring the coastline immediately, but dense fog and a stormy northeastern gale delayed his departure until July 21. Then, with his party now numbering twenty, including eleven frightened voyageurs, he began his exploration of the Arctic Ocean. The men knew that it would not be easy, and they were right. As they hung to the coastline, exploring every inlet and creek, they were assailed by heavy storms. The canoes took a terrible battering and began to splinter apart, striking even further terror into the hearts of the voyageurs. The several landings they made in search of food were almost totally unsuccessful. Yet somehow they managed to explore and chart 555 miles.

It was now August 15. Even the determined Franklin began to realize that it was time to call a halt to the journey. “In the evening,” he would later write in his memoir, “we were exposed to much inconvenience and danger from a heavy rolling sea, the canoes received many severe blows, and shipped a good deal of water, which induced us to encampâ¦Mr. Back reported that both canoes had sustained material injury. Distressing as were these circumstances they gave me less pain than the discovery that our people, who had hitherto displayed a courage beyond our expectation, now felt serious apprehensions for their safety. The strong breezes we had encountered led me to fear that the season was breaking up, and severe weather would soon ensue, which we could not sustain in a country devoid of fuel. I announced my intention of returning at the end of four days unless we should previously meet the Eskimos, and be enabled to make some arrangement for passing the winter with them.”

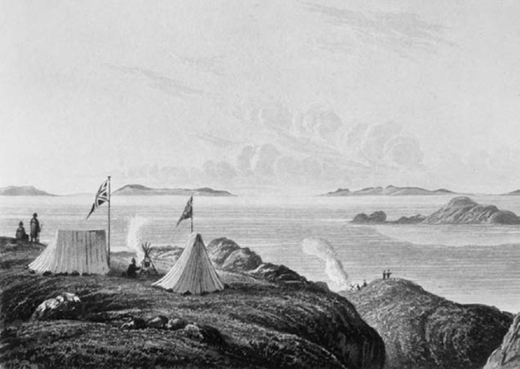

THE FRANKLIN PARTY'S

arrival at the Arctic Sea was a major accomplishment, one of the few triumphs of Franklin's otherwise disastrous first overland expedition. George Back, who proved vital to the survival of most of the party, drew this scene of Franklin's hastily erected camp on the bank of the Coppermine River, overlooking the sea.

On the eighteenth, even the ever-optimistic Richardson concluded that to continue would be pure lunacy. On that day, he and Franklin walked overland to a spit of land aptly named Point Turnagain. Franklin's journal notes that “it is possible Point Turnagainâ¦forms the pitch of a low cape.” They agreed that it was the appropriate spot from which to turn back. But even though he knew that winter was rapidly closing in on them, that the winds were rising, and that the sea was becoming increasingly turbulent, Franklin dallied for another five days. He had accomplished the goal of mapping a significant portion of the coastline. But perhaps, he thought, a few more days would allow him to spot a link to the Northwest Passage. It was a tragic blunder. Finally, on August 23, he gave the orders for the party to head back. Although he had placed his expedition in further jeopardy by delaying his return for so long, Franklin felt compelled to defend his indecision to turn back. In his published journal, he wrote:

When the many perplexing incidents which occurred during the survey of the coast are considered in connection with the shortness of the period during which operations of the kind can be carried on, and the distance we had to travel before we could gain a place of shelter for the winter, I trust it will be judged that we prosecuted the enterprise as far as was prudent and abandoned it only under a well-founded conviction that a farther advance would endanger the lives of the whole party and prevent the knowledge of what had been done from reaching England. The active assistance I received from the officers in contending with the fears of the men demands my warmest gratitude.

His disappointment at not finding a trace of the passage was shared by the other officers, including Backâwho nonetheless was convinced that the expedition had shown that it could be done, and wrote in his diary: “Thus ended the progress of our Expedition which we had fondly expected would have set at rest all future discussion on the subject of a passageâ¦It was now the season, not more particularly the want of food that stopped usâ¦. Be this as it may it must be obvious that we had incontestably proved the practicality of succeeding.”

IT WAS FRANKLIN'S INTENTION

to canoe back up the Coppermine as far as conditions would allow, but after struggling through the storm-tossed waves, he realized that the water route would have to be abandoned. They would have to make the return journey on foot and their first destination, the base camp at Fort Enterprise, was 325 miles away.

Winter was dead upon them by September 5. Three feet of snow fell, and temperatures plummeted to twenty degrees below. Franklin described their dire situation: “As weâ¦were destitute of the means of making a fire, we remained in our beds all the day; but our blankets were insufficient to prevent us from feeling the severity of the frost, and suffering inconvenience from the drifting of the snow into our tents. There was no abatement of the storm next day and; our tents were completely frozen, and the snow had drifted around them to a depth of three feet; even in the inside there was a covering of several inches on our blankets.” The men were so frozen and debilitated that they were barely able to pack after Franklin made the decision to move camp: “The morning of the 7th cleared up a little bit ⦠from the unusual continuance of the storm we feared that the winter had set in with all its vigour and that by longer delay we should only be exposed to an accumulation of difficulties; we therefore prepared for our journey, although we were in a very unfit condition for starting, being weak from fasting, and our garments stiffened from the frost. A considerable time was consumed in packing up the frozen tents and bed-clothes, the winds blowing so strong that no one could keep his hands long out of his mittens.”

They had now run completely out of food and were reduced to eating the lichen that grew on rocks and the boiled leather upper parts of their shoes. Their only chance for survival, Franklin decided, was to split up. On October 4, he sent Back and others off to see if he could find the Indians who had earlier abandoned them, hoping that if found, they would come to their rescue with food and supplies. Soon after Back departed, one of the voyageurs in his party, weakened by hunger and scurvy, dropped dead in his tracks. He was not the only one to have become desperately afflicted. Hood was so weak that he found it impossible to continue. To their credit, Richardson and Hepburn chose to risk their own lives by setting up camp, staying with him until help arrived.

In the meantime, Franklin and the remaining members of the expedition moved on. They had not gone far when four of the group decided that they would never be able to make it all the way to Fort Enterprise, still 350 miles away. Their only hope, they decided, was to head back to Richardson's camp. An Indian named Michel was the only one to reach the encampment. One by one, the others had died en route. For those in the camp, Michel appeared just in time, for he brought with him meat that he claimed he “had found from a wolf which had been killed by the stroke of a deer's horn.” Although the meat tasted unlike anything they had ever eaten, Richardson, Hood, and Hepburn were literally starving and devoured it greedily. But from Michel's questionable explanation of where it had come from and from the Indian's demeanor, Richardson began to have a sickening suspicion of what they had just eaten. To his horror, he became convinced that the meat must have come from the bodies of the voyageurs, who had died en route to his camp.

In the days that followed, Michel's behavior became increasingly disturbing to the others. At times the Indian, who was armed with both pistol and knife, became openly hostile. Then, on a day when Richardson was off seeking lichen, they were suddenly alarmed at the sound of a gunshot coming from their camp. Racing back they discovered Hood lying dead on the ground from, as Richardson described it, “a shot that had entered the back part of his head and passed out of the forehead.” Michel immediately claimed that Hood had taken his own life. But Richardson and Hepburn knew otherwise. They were certain that Michel had not only murdered Hood, but that when the opportunity arose he was determined to kill and cannibalize both of them.

With Hood dead, Richardson, Hepburn, and Michel broke camp and set out hoping to find either Franklin, or Back and the Indians he had gone seeking. Richardson had no doubt as to what he had to do as soon as possible. The first time he caught Michel off guard, the doctor acted. “I determined,” he stated in his journal, “as I was thoroughly convinced of the necessity of such a dreadful act, to take the whole responsibility upon myself; immediately upon Michel coming up, I put an end to his life by shooting him through the head with a pistol.”

Calling upon every ounce of strength they had left, Richardson and Hepburn were able, on October 29, to reach Fort Enterprise. And there were Franklin and three voyageurs. They had made it. But their joy was immediately tempered by the sight before them. “No language that I can use,” wrote Richardson, “[was] adequate to convey a just idea of the wretchedness of the abode in which we found our commanding officer [and the others]. The hollow and sepulchral sound of their voices, produced nearly as great horror in us, as our emaciated appearance did on them.” Franklin and the others were indeed close to death. Two days later one of the voyageurs passed away. But on November 7, just as all hope was fading, an advance party of Indians sent ahead by Back arrived with lifesaving supplies. Back had once again saved the day.

“Lieut. Back, Dr. Richardson, John Hepburn ⦠and I returned to York Factory on the 14 July,” Franklin wrote. “Thus terminated our long fatiguing and disastrous travels in North America, having journeyed by water and land (including our navigation of the Polar Sea) 5,550 miles.”

IT HAD BEEN A JOURNEY WITHOUT PRECEDENT.

And there had been some significant achievements. More than five thousand miles of uncharted wilderness had been crossed. Five hundred miles of unexplored Arctic Coast had been mapped. Back, at least, believed that the expedition had proved that finding the passage was possible. But Ross and Parry had already done that. What had been proven was that it was possible to survive in even the Arctic's most harrowing conditions.

Yet it had also been an unmitigated disaster. Eleven men had died. Two had been murdered. Although it would never be discussed in Victorian England, there had unquestionably been cannibalism. Ironically, Franklin, the architect of many of these disasters, returned home to fame and promotion. His published journal became an instant best-seller. The problems that his leadership had caused were almost completely ignored. He had become a hero simply by surviving. He was, after all, the man who had eaten his boots.

CHAPTER 4.

CHAPTER 4.The Indomitable Parry

“How I long to be among the ice.”

â

EDWARD PARRY

J

OHN BARROW

had spent sleepless nights deciding who should lead the overland expedition into the Canadian Arctic. He had no such problem choosing the man who would make the next attempt at finding the Northwest Passage. Barrow was convinced that if Edward Parry rather than John Ross had been in charge of the passage-seeking expedition they had conducted just one year earlier, there would have been no turning back because of imaginary mountains, and the prize would have been gained. While Parry had been as circumspect as he could in criticizing John Ross's behavior during their aborted search, he and Barrow were in total agreement that, as Parry would state, “Attempts at Polar discovery had been hitherto relinquished at a time when there was the greatest chance of succeeding.”

Parry set out just days after Franklin had left on his expedition, reached the Davis Strait on June 28, 1819, and proceeded on to Lancaster Sound. Ahead of him lay open water. There were no Croker Mountains. This time there would be no turning back. The same William Hooperâthe

Alexander's

purserâwho had expressed such dismay a year earlier over Ross's actions, now exclaimed, “There was something particularly animating in the joy which lighted every countenance. We had arrived in a sea which had never before been navigated, we were gazing on land that European eyes had never beheldâ¦and before us was the prospect of realizing all our wishes, and of exalting the honour of our country.”