Resolute (15 page)

Authors: Martin W. Sandler

I

T HAD NOW BEEN

more than five years since John Franklin had sailed away. The national anxiety over his disappearance, combined with the published reports of Richardson's and Ross's adventures in seeking him, emblazoned the mysteries and romance of the Arctic in the British national consciousness as never before. Newspapers became filled with accounts of past expeditions, of northern discoveries already made, of the ways in which the passage-seekers were bringing greater glory to the nation than even the most honored military heroes, all wrapped around the great burning questionâwhere was Franklin? The

Illustrated London News

led the charge:

Of all the expeditions which private enterprise and public policy has fitted out for the exploration of the still unknown regions of the globe, the several expeditions for the discovery of the North-west Passage are looked upon by the people of this country, and by the rest of the world in general, with the greatest interest and anxiety. The failure of one expedition is but the incentive to fit out another; and the greater danger, the greater is the eagerness of enterprising and resolute men, from the most able and experienced Commander to the hardest-working common sailor, to share it, upon the chance of imperishable renown which success will afford them. Captains Parry, Ross, Back, Franklin and their brave companions, who have been engaged at intervals for the last thirty years and upwards in the endeavor to solve this deeply interesting problem and to determine the configurations of the great North American continent⦠have carried with them on their departure the cordial good-wishes of their countrymen for their success.

Their return in safety, after the manifold privations and hardships of such a voyage has invariably been greeted with fervent enthusiasm; and the long absence of Sir John Franklin, the last gallant explorer of those seas, has excited in the public mind an affectionate and deep interest, amounting at last to a painful solicitude for his fate and that of the brave men who share his perils and his glory.

Actually, it was far more than “a painful solicitude.” Finding Franklin had become nothing less than a crusade. “Since the zealous attempts to rescue the Holy Sepulcher in the Middle Ages,” one newspaper exclaimed, “the Christian world has not so unanimously agreed on anything as the desire to recover Sir John Franklin, dead or alive, from the dread solitude of death into which he has so fearlessly ventured.” (The search for Franklin became such a cause célèbre that it was the subject of many songs and poems, see note, page 266.)

All England was now caught up in the great concern. In one gigantic outpouring of emotion, prayers for the expedition's safe return were said in sixty different churches. More than fifty thousand citizens attended the services.

Not surprisingly, the most visible concern was that expressed by Lady Franklin. More than ever, she was doing all she could do to facilitate the search for her husband. Determined to try everything, she even visited a psychic, hoping to hear that Sir John was still alive and learn where in that vast, frozen wildness he might be found. She spoke with everyone she could, anyone who might suggest anything that might be done. Accompanied by her friend and advisor, William Scoresby, she traveled to various ports from which the Arctic whalemen departed and implored them to carry extra food and supplies in the event they came upon the missing expedition. And, as she had done when she had so successfully campaigned for her husband's selection as commander of the expedition, she devoted hours to letter writing. Putting national pride aside (John Barrow would have been appalled), she even wrote to the newly elected American president, Zachary Taylor, imploring him to launch an American search. The obsession that England or that even Sir John must be the first to find the passage was no longer her concern. All that mattered was that her husband be found. “I am not without hope,” she wrote, “that you will deem it not unworthy of a great and kindred nation to take up the cause of humanity ⦠and thus generously make it your ownâ¦I should rejoice that it was to America we owe our restored happiness.”

Once again her efforts energized the press. Increasingly they adopted the theme that much more had to be done. Even Ross's and Richardson's efforts had been lacking, they intimated. The London

Times

spoke for them all when it dared ask why both expeditions had given up the search while their ships were still loaded with so many provisions. “We shall never attain our end,” explained the newspaper, “by sailing up to the ice and then back again.”

The public agreed. “Let 1850 be the year to redeem our tottering honour,” a reader wrote to the

Times.

Obviously the writer was aware of the letter that Jane Franklin had written to the American president but, unlike Lady Jane, was not willing to surrender British pride: “Let not the United States snatch from us the glory of rescuing the lost expedition,” the writer pleaded.

Togetherâpress, public, Lady Franklinâit was pressure that even the most recalcitrant member of the Admiralty could not withstand. The result was the launching of the greatest activity the Arctic would ever witness. In the next twelve years, as many as forty ships and more than two thousand officers and men would join in the search for the Franklin expedition. It would be the longest and most expensive search and rescue mission ever undertaken.

It began on January 20, 1850, with an expedition commanded by Captain Richard Collinson aboard the hastily refitted

Enterprise.

Joining him as second-in-command was Lieutenant Robert McClure, in charge of the

Investigator.

Theirs would be the first of six expeditions that would head for the Arctic before the year was out.

Two more different leaders could probably not have been chosen. The painfully thin, often dour Collinson was a cautious man, averse to taking risks, while the muscular and animated McClure was known for his mercurial nature. He was also extremely ambitious. This was his first command and he was ready to do almost anything to gain the renown that came with finding Franklin, or maybe even the passage.

Because James Clark Ross had vividly described the impenetrable ice that blocked Barrow Strait, the expedition was given orders different from most of their predecessors. After sailing around Cape Horn to Honolulu for a supply stop, they were to enter the Arctic from the west and then make their way eastward. Whichever ship reached Honolulu first was to wait for the other so that they could conduct the search together. But when McClure, who had been separated from Collinson on the voyage over by fog, reached Honolulu, he discovered that the commander, having waited for four days, had left the island and had headed for the Arctic. To his even greater consternation McClure was given a message telling him that if he did not catch up with Collinson, the commander would replace the

Investigator with

the

Plover

, the ship that had originally been sent to assist James Clark Ross's expedition, and which was still in the Bering Strait.

McClure was beside himself. Was he to lose his big chance by being replaced by a supply ship? He most certainly would miss the glory he craved if Collinson were to find Franklin before he did. The next scheduled rendezvous point for the two ships was at a spot near Bering Strait. He knew that Collinson would travel to that point by sailing around the Aleutian Islands. Without hesitation, McClure made his decision. He would cut straight through the islands, chancing a route that would require him to navigate through dangerous, shallow, and uncharted waters.

It would not be the last time on the fateful voyage that McClure would risk his ship and the lives of his men to feed his ambition. But he made it. Negotiating the thick fog, the tumultuous tides, and the ever-present reefs and shoals that characterized the inner Aleutian waters, he entered Kotzebue Sound on July 29, days ahead of when Collinson could be expected to arrive.

Now McClure's actions turned into outright deception. Shortly after entering the sound, he surprisingly encountered another naval vessel. It was the

Herald

, one of the ships that had been originally sent in 1848 to supply James Clark Ross and John Richardon, but had stayed on in the Arctic to search for Franklin. The

Herald w

as commanded by captain Henry Kellett, an officer superior in rank to McClure. When Kellett came aboard the

Investigator

, McClure brazenly told him that he was sailing behind Collinson and that he was racing to catch up. A veteran explorer, Kellett was not deceived. He knew that McClure was lying. Kellett had been receiving updates from the Admiralty from passing ships, but had been given no orders from the Admiralty as to what to do should the

Enterprise

and the

Investigator

fail to rendezvous in the Arctic. Convinced that his main duty was not to impede the search for Franklin, he “swallowed” McClure's false tale, decided not to pull rank by ordering that McClure wait for Collinson, and reluctantly allowed him to sail on.

Although he had no way of knowing it, McClure's true adventure was about to begin. Only a few days after leaving Kellett, he encountered solid ice but, refusing to stop, he plowed his way through the pack. Reaching Point Barrow and finding it completely icebound, he ordered forty of his men into five of the boats and had them haul the

Investigator

around the point. He was now in waters off northern Alaska into which no white men had ever entered. Seeking Banks Land, he tried to enter every channel he encountered, only to find his way totally blocked. All along the way he was surrounded by the tallest, most spectacular Arctic cliffs that any European had ever seen.

But McClure had little time to admire them. Suddenly the

Investigator

was stuck by a fierce gale, so strong that it completely took over control of the ship. Unable to do anything but struggle to keep the vessel upright, he was driven along by wind and ice until, on August 7, he reached a mountainous land dominated by two-thousand-foot peaks. Thankful to still be alive, he planted a flag and named it Baring Land, after the first lord of the Admiralty. (McClure didn't know it but it was actually Banks Land, the very region he had been looking for. Nor did he know that it was really an island).

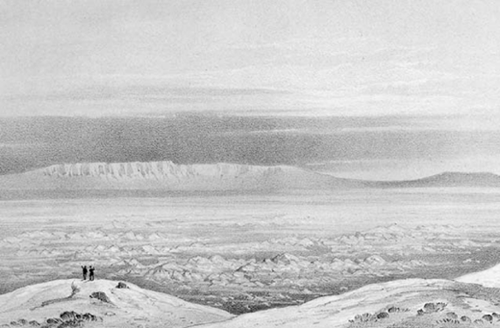

THE CREW OF THE

Investigator

included Lieutenant Samuel Creswell, a gifted artist. His dramatic drawings illustrated the major events in the voyage that resulted in the discovery of the last link in the passage. Here, two members of the ship gaze out at the long sought-after final linkâthe frozen gap between Banks and Melville Islands.

He had been fortunate thus far and now he got even luckier. Once again the wind and the flowing ice picked up. Once again he had no control over where he was being taken. Unwittingly he was being driven northward up a narrow channel. What was this waterway? No other explorer, he was sure, had ever entered it. Was it yet another dead end? Or could it be a strait leading toâhe hardly dared think of the possibility. “I cannot describe my anxious feeling,” he would later write in his published account of the expedition. “Can it be possible that this water communicates with Barrow's Strait and shall be the long sought North West Passage? Can it be that so humble a creature as I am will be permitted to perform what had baffled the talented and wise for hundreds of years?”

Never in his life had McClure been so excited; he was eager to confirm that the waterway linked up with areas already discovered, making it the final connection between the West and the East. But then his luck turned against him. Ahead of him, he discovered, the channel was completely frozen over, much too thick to even attempt to try to plow through. Winter was definitely setting in. Should he head back south and find a safe shelter for the winter? Or should he remain where he was, risking the elements in this unprotected spot? For him, one thing was certain: Before making his decision he had to know that this epic discovery was real. The next day he sent his ice mate up to the crow's nest where he could see for twenty miles. And there in the distance was a vast expanse of open water.

For McClure, there was no choice. He had to winter in the pack so that in the spring he could complete the passage. Once more he would be risking the ship and the lives of all aboard. But he was too close to retreat now. Then, for the third time, the Arctic weather controlled his fate. As stronger winds than he had yet encountered blew in, the

Investigator

was torn from the ice and driven thirty miles back up the channel. For more than a week the vessel was pounded relentlessly until, on September 26, McClure was certain it was about to be blown apart. Calling all hands on deck, he was ready to give the orders to abandon ship when miraculously the winds abated. Yet again he had escaped disaster.