Plymouth (9 page)

Authors: Laura Quigley

With inadequate maps amidst stormy conditions, the navigator was sailing ‘blind’, and they arrived not at their destination but many miles north, at Cape Cod. An attempt to sail south nearly brought destruction in the Pollack Rip, a treacherous maze of shoals and sandbars. Surviving only by a fortunate change in the wind, they limped back to Cape Cod. Though beautiful, it was a sandy harbour, a wilderness inadequate for a plantation, and they were 500 miles from the nearest English settlement. And it was starting to snow. New England snow.

They had to steal from the natives’ stores of corn to stay alive. The nearest tribes had good reason to hate the English on their ‘floating islands’: a previous ship had captured many of their men and shot them in cold blood. The pilgrims’ first attempt to explore and find a decent location for their settlement put them at the mercy of a rain of arrows as the natives opened fire.

On 20 December 1620 the pilgrims finally decided upon a permanent settlement near Plymouth Rock. The land had much to commend it – a 165ft hill gave them defence and a good view, and there was an unusually good supply of fresh water. What they couldn’t see was the area’s infected history. Three years before the pilgrims landed, the area had been populated by around 1,500 natives, the shores dotted with hundreds of wigwams and fields of corn. But 1619, just before the arrival of the pilgrims, an epidemic hit the land, one which left only skulls and bones dotted around Plymouth Rock. The pilgrims had unfortunately chosen a site of pestilence, and during the next four months half of the pilgrims would perish.

But still the survivors were determined to flourish. One indentured servant on the voyage, John Howland, managed to survive falling off the

Mayflower

in the middle of the Atlantic. He’d gone on deck, desperate for some air, and the gales tossed him overboard. Even though he was pulled 10ft under the stormy waters, John wouldn’t let go of a trailing rope and they managed to bring him back on board. He went on to have ten children and an astonishing eighty-eight grandchildren, all of the same hardy constitution as their grandfather.

1608

TO BE A PIRATE

K

ING JAMES I

made peace with Spain, and forced many seafarers into unemployment. No longer were the West Indies the source of stolen Spanish treasure; no more would privateers have a royal licence to steal gold and silver from the Americas. In 1608 four pirates were executed and buried at Plymouth, arrested by Sir Richard Hawkins, Vice Admiral of Devon and son of the celebrated Sir John Hawkins. When Sir Walter Raleigh stole Spanish gold in Guiana, he was declared a traitor to the new King and beheaded. Plymothians were unimpressed by the King’s treatment of their favourite courtier.

So the pirates moved their criminal dealings to new shores in North Africa, and built ocean-going vessels for their new allies, the ‘Turkish corsairs’ – many built by a Plymouth-born man called William Bishop. But these developments brought new dangers back to English waters. In 1625 Sir James Bagge, the corrupt official in charge of Plymouth Sound, reported that a Turkish pirate ship had attacked three Cornish fishing boats and a ship from Dartmouth. The crews were either killed or taken as slaves to work the Turkish ships – which ironically had been designed by William Bishop!

Suddenly foreign slavers were raiding the coasts of Devon and Cornwall, stealing away fleets of fishermen to take as slaves, or women from the villages to sell in the markets in North Africa and the Middle East. The Mayor of Plymouth complained to the King that 1,000 Plymothians had been captured – though this was probably a slight exaggeration, it still reveals the fear of piracy that haunted the shores, keeping fishing fleets from going out and putting impossible pressures on the customs officers and local Navy forces to defend the coast.

Corsairs dogged the merchant ships making for Plymouth. One Moroccan ship passing Plymouth Sound was taken, and actually brought into the Cattewater as a prize. The courts railed against it all, but it seems they could not trust their own Navy or the local Plymouth authorities to prevent it. Corrupt local officials were often sequestering foreign ships and pillaging the contents for themselves. The pirate chief of Devon, Captain Nutt, paid his men so well that the sailors of the Royal Navy frequently ‘jumped ship’, and the Plymouth merchants were forced to pay for their own protection. Plymouth’s maritime status and reputation deteriorated rapidly.

Sir John Eliot, Vice Admiral of Devon, tried to put paid to all the corruption, He regularly hanged captured corsairs and tried to get Captain Nutt put into gaol. However, it seems that Nutt had powerful friends in high places and it was Sir John Eliot who, conspired against, eventually found himself in gaol – held on a charge, ironically, of corruption, accused of accepting a £500 bribe from Nutt to release him.

Not all pirates, however, were cruel cut-throats. Born in Plymouth of lowly status, Captain White was in the merchant service in Barbados when he was captured by a French pirate who took him and his crew as slaves, and burnt and sank his brigantine. The crew were then used as target practice by the pirates.

Captain White and what remained of his crew eventually escaped the pirates and paddled in a long boat to Augustin Bay. There they found themselves strangers in a strange land, with no transport to make their way home, so they agreed to join another pirate ship captained by William Read. Read steered a course for Madagascar and White reluctantly assisted in Read’s raid on the Bay of St Augustine.

The raid was a disaster, but White survived, and after many adventures – and forced service aboard many a pirate ship on his quest to reach home – he found himself captain of his own pirate ship, where he was noted for gallantry and a generous nature. He eventually retired, with an enormous fortune, at Hopeful Point, Madagascar, built a house, raised cattle, and found himself a woman by whom he had a son. But the lure of pirate adventures was too much, and White decided to join a Captain Halsey on just one more raiding party. It would be his last. He would never make it back to England. He returned after the raids very ill, and died six months later. His last wish was that his son be taken to England aboard the first ship that passed. Some years later, this wish was fulfilled when an English ship touched in at the harbour and the boys’ guardians faithfully discharged Smith’s last wishes – the boy was adopted by the English captain and brought up to become a good man and to live a better life than his father.

Henry Avery, or Every, was also born in Plymouth. The son of an innkeeper, like White he joined the Royal Navy heading out to the West Indies, but there end any similarities. Avery soon grew tired of the naval life and mutinied, setting the captain off in a boat and taking the ship for himself.

Re-naming the ship the

Fancy

(a little bit of what you fancy...?), Avery and his crew set out to be pirates in the Red Sea, preying on the wealthy merchant ships sailing between India and the Middle East. The sixth ship he captured, the

Fateh Mahomed

, was carrying gold and silver worth £50,000. His next was to be the most famous pirate prize ever taken: the

Gang-i-Sawai

, ‘the Exceeding Treasure’.

The

Gang-i-Sawai

was owned by the Great Mogul and carried a large crew and sixty-two guns: too much of a match for Avery’s ship on its own, but helpless against the fleet Avery assembled to take her. Avery’s first shot managed to damage the

Gang-i-Sawai’s

main mast, and one of her Indian cannons blew up on deck. While the fighting continued, Avery’s allies secretly circled the ship and boarded her. The desperate defenders suddenly found themselves surrounded by Avery’s men, just as the

Fancy

came up alongside.

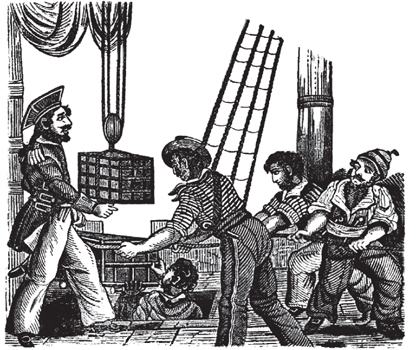

Treasure coming aboard Henry Avery’s ship, the

Fancy

. (Avery is the man on the left.)

What happened next on the

Gang-i-Sawai

is nothing short of a horror story. The pirates had made one of the largest hauls in history, each man receiving £1,000, but the money was not enough for these blood-thirsty men. The crew of the

Gang-i-Sawai

were tortured until they revealed the location of any further treasures hidden on board, and then slaughtered. In the course of these horrors, the pirates discovered that several women were on board, disguised as men to shield them from the pirates’ attentions. An elderly relative of the Mogul, along with her servants and all of the female passengers, were savagely assaulted for several days. A number of the victims died. One passenger killed himself, his wife and their servant to avoid being made to watch the carnage and depravity, while others threw themselves overboard in despair.

Days later, the

Fancy

and the other two pirate ships finally left, and the discovery of the

Gang-i-Sawai

and its tortured passengers caused an international outcry. The English were forced to make a very humbling apology to the Great Mogul to ensure trading relations, and promised to catch and execute every one of Avery’s men.

Avery, in the meantime, suggested to his fellow pirate captains that all of the loot would be best held aboard the

Fancy

until they reached a safe harbour at Madagascar. This was agreed – the other captains not being very bright – and the following morning they awoke to discover Avery had sailed off with all the spoils. In the Bahamas, a bribe to the Governor assured Avery’s safety and he quietly disappeared.

After an expensive international man-hunt, the English managed to find only six of Avery’s loathsome crew, who were duly hanged. Avery himself escaped justice and disappeared into wealthy obscurity.

1675

THE BURNING GIRL

S

UMMER 1675, AND

the day began like any other for the Weeks family in Plymouth. Mr Weeks prepared to go to work; he ran a business dyeing cloth. His widowed daughter, Mary Pengelly, lived with him and was busy feeding her own infant daughter – with the help of Philippa Carey, a nurse in her twenties whom Mr Weeks had employed to help with the baby. Fifteen-year-old Anne Evans served Mrs Elizabeth Weeks her porridge. Anne was their indentured servant, an orphan ‘bound’ to the Weeks family three years before by the Plymouth Corporation, following the death of her mother. It was a normal day.

But, as in all families, there were tensions. Anne was unhappy with her lot, and had been overheard declaring that she wanted to run away. Mrs Weeks was a tough employer who, a few days earlier, had argued with Philippa Carey, accusing the nurse of adultery. Carey, apparently estranged from her husband, had openly admitted her sin and declared that it was none of Mrs Weeks’ business.

So, on this particular summer’s day, Mrs Weeks demanded her porridge and Anne Evans served it. Philippa Carey poured a mug of beer for Mr Weeks – beer was a more healthy option than water in the seventeenth century – but Mr Weeks declared the beer tasted ‘odd’ and passed the mug to his daughter Mary, who agreed – it did taste odd.

Suddenly Mrs Weeks did not feel well. She vomited, and went into severe convulsions. She was put to bed in agony, but died just a few hours later. As Mrs Weeks lay dying, Mr Weeks and Mary also fell ill, stricken by terrible stomach pains. Mr Weeks recovered, but his daughter worsened and soon followed her mother to the grave.

Faced with this sudden and inexplicable disaster, Mr Weeks could see only one solution: ‘poison!’ he cried, pointing an accusing finger at the servants. Anne was brought before the mayor for questioning and declared that she had bought a pot of groats (a mix of whole grain cereals) in the market. However, when they were made into porridge she claimed to have found a yellow substance in the pot. The family must have eaten this, she said, and been accidentally poisoned. In her testimony, Anne mentioned the argument between Mrs Weeks and Philippa Carey; Carey in her turn confirmed this, before accusing Anne Evans of the murders. The mayor realised there was no love lost between the servants, and played one girl against the other – and the servants damned each other to death.