Plymouth (19 page)

Authors: Laura Quigley

Meanwhile, the brave Mr Edsell came alongside the

Dutton

in a small boat to bring two more ropes, increasing the flow of passengers transported to safety, starting with the women and children. A master attendant from the Royal Dockyard also managed to bring a larger boat alongside and saved hundreds of lives, as Pellew firmly calmed the panicking passengers (and knocked down some drunken soldiers who threatened anarchy). It seems that the ship’s officers, in the panic, had given up any hope of saving the passengers. Pellew was therefore forced to take command.

With the water rising over the deck, Pellew swiftly turned anarchy into order. He himself saved a three-week-old baby after reassuring the distraught mother that the child would be safe in his care. Only after the last of the passengers was safely on shore did Pellew and Edsell escape, leaving three crewmen to release the rescue ropes.

Total disaster was averted, and the number of casualties reduced from four hundred to fifteen. The heroic Captain Pellew, just twenty-nine, was awarded the Freedom of the Borough and knighted by the King.

However, the same year brought further disaster – but this time the casualties were far higher. The frigate

Amphion

had pulled into Plymouth for repairs and was hosting a farewell dinner for the crew, who were preparing to sail the following day. The ship was crowded with soldiers, their sweethearts and families, most from Plymouth. Over 300 people were on board, more than the usual compliment.

Their festivities turned suddenly to terror: the masts lifted, as though they were forced upwards, and the hull immediately sank. The sea boiled and hissed as flames shot up and then subsided. In Plymouth it felt like an earthquake. The sky reddened with a spray from bloodied and broken limbs, and headless bodies suddenly littered the deck. Heads blackened by gunpowder splashed into the sea like cannonballs. William O.S. Gilly published an account of the tragedy in 1864:

Strewed in all directions were pieces of broken timber, spars and rigging, whilst the deck of the hulk, to which the frigate had been lashed, was red with blood, and covered with mangled limbs and lifeless trunks, all blackened with powder. The frigate had been originally manned from Plymouth, and as the mutilated forms were collected together and carried to the hospital, fathers, mothers, brothers and sisters flocked to the gates, in their anxiety to discover if their relatives were numbered amongst the dying or the dead.

In the dining room Captain Israel Pellew had been thrown off his seat by the first explosion, but by some force of instinct he and his first lieutenant rushed to the cabin window before the second explosion blew them into the water. They were lucky to survive. The boatswain on the deck was blown off his feet and recovered consciousness only to find himself tangled amongst the rigging, his arm broken. Fortunately he had a pocket knife with him, and cut himself free.

Of the 300 on board, only eleven survived. One survivor was a child whose mother had held him in her arms to protect him as the explosion hit them both. The force tore her body in half, but still her arms were clasped around him as he was pulled from the wreckage. She never let go. The child was taken into care and joined the Navy, where it is said he had a successful career.

As the wreckage was scoured for survivors, the relatives on shore were faced with the task of identifying their loved ones from the bags of limbs and carcasses brought to land. Body parts were washed ashore with every tide.

As to the cause, the discovery of a sack of powder established the theory that a gunner, probably drunk, accidentally dropped some powder whilst attempting to steal from the stores. This ignited, and in its turn caught the main magazine. The thieving gunner died in the blast.

![]()

In 1824, ‘The Great Storm’ hit Plymouth, decimating the south coast and ripping 200,000 tons of stone from the Breakwater. The ferocious seas and gales threw boats around like matchsticks, with over twenty boats driven ashore. The gunners from the Citadel set out on the stormy harbour and rescued 200 mariners from the stricken vessels in the Sound.

![]()

In 1836 an accidental fire at the house of Major Watson at the Citadel proved fatal. The family and the household retired to bed about 1 a.m., but a servant had left some wood on the extinguished fire to dry overnight and sparks set the house alight. The alarm was raised and most of the family managed to escape – though the eldest son, John, who was blind, had to be helped by servants. The seventy-year-old Major Watson rushed to a second-floor bedroom to attempt to rescue two of his daughters, Elizabeth (twenty-two) and Marion (sixteen), but all three succumbed to the smoke and burned to death. By morning the house was destroyed, with only the fireplaces remaining.

On 23 August 1839, at 6 p.m., a match factory on Woolster Street burst into flames. For the partners, who would go on to become the famous match-making business Bryant and May, this first endeavour obviously proved to be a short-term venture, as by 7.40 p.m. the roof had caved in, and the fire was spreading towards the nearby custom’s warehouses of bonded spirits – threatening a major explosion. To add to the danger, the match factory also contained stores of gunpowder. Fortunately, however, fire engines from around the city, including the Royal Dockyard, hurried to the scene, quenching the flames and leaving the premises a pile of smoking ashes.

In 1832 the terrible sanitary conditions in Plymouth brought on a cholera epidemic that killed 1,031 people. The Plymouth Board of Health desperately tried to control it and the mayor ordered streets to be flushed with water on alternate days. ‘Station’ houses were established throughout the city to provide blankets, fuel and medicine to victims. The Ford Park Cemetery opened in 1848, and within months a further 400 cholera victims were buried there.

After the castle at the Barbican was demolished, the area was rebuilt into many tiny houses that soon became over-crowded and dilapidated. One survey recorded 564 people living in 30 houses, 13 with no sanitary facilities. By 1850, Castle Street – or Damnation Alley, as it was better known – was a filthy slum noted for debauchery, over a dozen of the thirty houses turned into notorious brothels. A Government report in 1852 suggested the conditions were the worst in Europe, with the exception of Warsaw.

Concern for the moral welfare of the area led to the building of the Bethel Chapel on Castle Street in 1833, which is now the Barbican Theatre. St Saviour’s church was built on the top of Lambhay Hill, though it was later destroyed by the bombing in the Second World War. But the debauchery simply moved west, to the Octagon, where, in 1861, the ironically named James and Louisa Churchward were committed for nine months’ hard labour for running a house of ill-repute. This ordinary residential home provided round-the-clock services to the local residents, with women sitting in the windows beckoning in prospective customers and male clientele coming and going at all hours. Their neighbour, John Risdon, recounted how the Churchwards’ two adult daughters contributed to their parents’ income through prostitution. Their houses were separated only by a thin plaster partition, so he could hear everything that was going on. Despite being threatened with violence by the Churchwards on more than one occasion, he was so revolted by their behaviour that he stood by his front door with a lantern and shone it in the faces of their clients as they left.

The New Palace Theatre on Union Street, now sadly derelict, first opened its doors on 5 September 1898. With sumptuous stage boxes, stalls, grand circle and gallery, it could seat around 2,500 people. Sadly, just four months later it was devastated by fire, and had to be restored and re-opened. It is known to be haunted by an actress, and also a woman called Mary, thought to have died in the fire. A security guard in the 1980s had a terrifying experience whilst patrolling the building with a colleague: at about 3 a.m., the two men heard a woman scream – and all the lights went out.

Mrs Hunn was the mother of the Prime Minister George Canning and an actress. While performing at the New Palace Theatre, she found digs in Plymouth, in a first-floor flat above what had once been a carpenters’ workshop. Every night she could hear the sounds of the ghostly carpenters still hard at work, sawing and hammering, even though there was no one downstairs and the door to the street was locked. She mentioned it to the theatre manager, who told her she should leave the flat. Mrs Hunn replied, rather stoically, that the noises didn’t worry her – she was more concerned that the noises might stop and the hard-working spirits decide to rest and come upstairs!

![]()

Private William Laskey was murdered as he slept in 1877. He had gone to bed intoxicated, and there Corporal Joseph Hector and Private John Mutter attacked him. They kicked and punched him, causing such serious injuries that he died. Others in the room were threatened with the same treatment if they gave the alarm. At the Exeter Assizes the murderers were found guilty of manslaughter and given twelve months’ hard labour.

![]()

In 1908 another tragedy occurred involving a Plymouth theatre, when fifteen-year-old Clara Jane Hannaford had her throat cut just outside the old Theatre Royal by her nineteen-year-old stalker. The obsessed murderer, Edmund Walter Elliott, had followed Clara and her boyfriend to the old theatre. There he called Clara out into the street – where he pulled out a razor and slit her throat. Edmund gave himself up, but calls for clemency on account of his youth were ignored. He was hanged in March 1909.

![]()

On 28 April 1912, the

Lapland

arrived in Plymouth carrying 167 survivors of the sinking of the RMS

Titanic

. The ‘unsinkable’

Titanic

sank on her maiden voyage after being holed by an iceberg, with 1,517 lives lost in the freezing North Atlantic waters. The

Lapland

anchored in Cawsand Bay, and the passengers were slowly transferred to the

Sir Richard Grenville

, which was supposed to bring the survivors ashore at Millbay Dock. However, the Board of Trade delayed disembarking the passengers until each had been served with a subpoena requiring them to give evidence to the Receiver of Wrecks at Plymouth. Millbay Dock was closed off, guarded by police to prevent any passengers from leaving, but the furious survivors rebelled, refusing to give any evidence at all until their illegal detention was lifted.

![]()

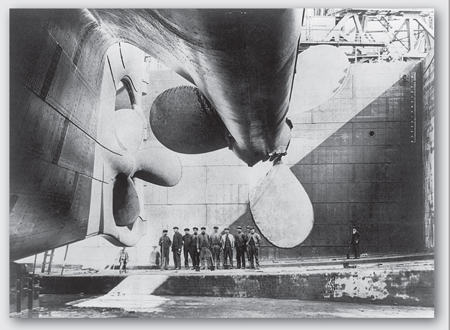

Titanic

launching – a haunting shot of a boat that would take most of its passengers with it to the depths of the ocean. The few survivors who sailed into Plymouth were not best pleased with their reception... (LC-USZ62-34781)