Plymouth (5 page)

Authors: Laura Quigley

The Cattewater in Plymouth Sound. (With the kind permission of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto)

King Henry IV retaliated quickly to avenge the destruction of Plymouth. From Dartmouth in October 1403, he sent the English fleet under the command of William de Wilford to attack Brittany, burning forty ships and seizing 1,000 tons of wine. His forces then laid waste large areas of Penarch and St Mathieu. In 1404 du Chastel was back, this time with the Breton Admiral Jean de Penhors, and the Breton fleet attacked Dartmouth. However, Dartmouth’s defences had already been strengthened in preparation for the attack and du Chastel was killed in a hailstorm of arrows. A reported 100 prisoners were taken, including du Chastel’s brothers.

Although the Breton Admiral escaped and England would continue to fight over lands in France, including their astounding victory over the French at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415, the Devon coast at last remained free from further French attacks – at least, for the time being…

1403-1588

SCURVY DOGS

T

HE MODERN IMAGE

of English pirates as colourful rogues is far from the truth. Piracy was a profession for bloody-thirsty murderers and thieves, evil marauders intent on destruction and lining their own pockets. Yet some of the worst worked for the government – there was a very fine line between the criminal pirates and the government’s paid ‘privateers’, determined only by who they were attacking at the time.

During the Hundred Years’ War, with so many English men fighting in France, Plymouth – like many coastal towns – was overrun by pirates and brigands. While the English forces were raiding French ships in the Channel in acts of war, the pirates were raiding all the other ships in acts of terrorism – the distinction between the two attacks only based on the nationality of the victims. To be fair, the men at sea could not always be expected to distinguish which ships were French, so any foreign ships were seen as the enemy and therefore ripe for plundering.

The first mention of a pirate in Plymouth is Henry Don in 1403. In the midst of the worst French attacks on the town, he was caught thieving and pillaging the wrong foreigners and was requested to appear before the authorities in London, along with many others from the South Coast, charged with piracy.

Of course, piracy did not start with the Hundred Years’ War. The Norman Baron de Marisco established his own pirate fiefdom on Lundy Island in the Celtic Sea in the thirteenth century. He made the mistake of plotting to kill King Henry III, and was subsequently the first man to be hanged, drawn and quartered. This grotesque punishment, invented for de Marisco, was also used in Plymouth at a later date.

In April 1548 a commissioner trying to establish the English Prayer Book in the West Country was stabbed by a priest, and the priest’s execution fuelled riots known as the ‘Prayer Book Rebellion’. A protesting Cornish army gathered and headed east to attack Trematon Castle and then Plymouth, where they were met with guns on North Hill. It then proceeded further east to besiege Exeter, but the army was crushed. In fact, the King’s troops captured so many Cornishmen that they decided it would be most convenient to simply execute the prisoners on the spot. Nine hundred bound and gagged men were forced to their knees, and their throats slit one by one. It took just 10 minutes to murder all 900 of the prisoners. A Tesco store, Exeter Vale, now stands on the site of the massacre.

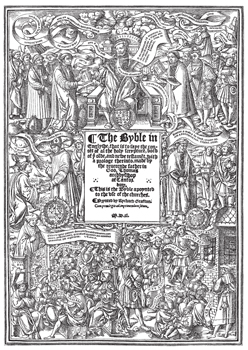

The beautifully elaborate title page of Cranmer’s 1540 translation of the Bible: source of the Book of Common Prayer which sparked the Prayer Book Rebellion of 1548.

The gallows in Plymouth ended the lives of most of the remaining Cornish ‘traitors’, but one was chosen for the special treatment of being hanged, drawn and quartered. First, the doomed man was dragged by a horse from his cell along the cobbled streets up onto the Hoe. He was there hanged by the neck but cut down before he lost consciousness, then stretched out while his genitals were cut off, his stomach cut open and his intestines pulled slowly out from him. Finally, his heart was cut out and burned. He was forced to watch all of these actions. Of course, death followed very quickly after the last act, but the lifeless body was further desecrated – a horrific act in the days when people believed that the body should remain intact in readiness for the Rapture, when the dead would be resurrected and transported to heaven.

His head was cut off and set on a pole fixed to the Guildhall with ‘cramps of iron’, and his body cut into quarters. One quarter joined the head on a second pole, while another was carried by John Matthew to Tavistock. John Wylstrem was paid to perform the grisly execution and the under-sheriff of Cornwall was forced to watch, quite likely as a warning to his fellow Cornishmen never to attack Plymouth again.

Surprisingly the pirates from Plymouth never suffered the same fate, perhaps because they themselves were often men of high standing or protected by high-ranking benefactors. It was the high-ranking Hugh Courtenay from Cornwall who led a pirate attack on a Spanish ship moored in Plymouth in 1449. Though Hugh was a namesake of the illustrious Earl of Devon who had so successfully defended the town just fifty years earlier, he was no close relation, but he was still an important official. He escaped punishment and simply took his spoils back with him to Fowey.

As the aristocracy took the profits, the pirates themselves reduced in numbers, recruited into the wars against France and then Spain in the progression of the Tudor monarchs from King Henry VIII to Queen Elizabeth I.

However, as the coasts of the Americas were explored and exploited by the Spanish and Portuguese, the seas of the sixteenth century belonged to a new age of English pirates, raiding the same coasts and the Spanish settlements for gold and glory. But they were no longer pirates: with the backing of the crown, they were now officially privateers. For 100 years, more expeditions to the New World set out from Plymouth than from all the other English ports combined, and most were intent on theft.

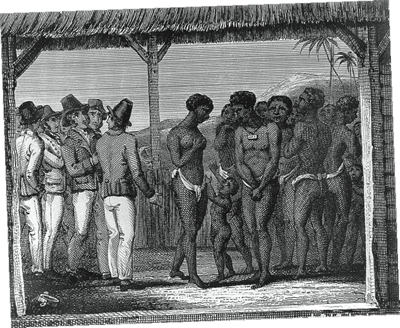

Sir John Hawkins was born in Plymouth in 1532 into an illustrious family of mayors, captains and merchants. While his older brother William was fitting the ships to defend Plymouth against the Spanish, John was hell-bent on a very different trade. From his early voyages to the Canary Islands, he learned that the Spanish were in need of slave labour, and in 1562 he set out for the Guinea coast to capture West Africans as slaves.

Hawkins was by no means the first slave-trader, but his genius was to systemise and legitimise the process. With important London backers, he set out with three ships and 100 men and raided Sierra Leone, taking or purchasing around 300 slaves. In the West Indies, he traded these prisoners for hides, ginger, pearls and sugar and returned to Plymouth wealthy and triumphant.

In 1564 he repeated the sickening ‘Triangle’. Now backed by Queen Elizabeth I herself, his fleet travelled inland along the West African waterways and attacked the villages – and Hawkins’ men were brutal in their efforts, eventually taking around 450 slaves to sell along the coasts of South America. At first the Spanish refused to trade the slaves: they had signed an exclusive trade agreement with the Portuguese, though they told Hawkins they might consider taking the slaves off his hands if he paid them ‘import taxes’. Hawkins instead threatened to burn the town, whereupon the Spanish relented. Hawkins then returned to Plymouth in 1565 with a bounty of gold, silver, pearls and jewels, and a 60 per cent profit for his delighted investors. John Sparke, twice mayor of Plymouth, travelled with Hawkins and included the first mention of potatoes and tobacco in his diaries. Sir Walter Raleigh would be credited with their discovery, but it was Hawkins’ men who saw them first.

Privateers and scourges of the Spanish: Sir Martin Frobisher, knighted for his services against the Armada, died in Plymouth on 15 November 1594. He once accidentally transported 1,550 tons of worthless iron pyrite from Canada to England, believing it to be gold. The other two men are Sir John Hawkins and Sir Francis Drake, whose adventures are described underneath.

Elizabeth I granted Sir John Hawkins with a coat of arms that included at the crest a bound African slave. Sir John was appointed ‘Admiral to the Queen’s Navy’ – which in 1567 was residing in the Cattewater when fifty Spanish ships entered Plymouth Sound and failed to lower their flags in respect to the English fleet. Hawkins ordered his gunner to shoot the Spanish admiral’s flag. The Spanish ignored his threat, and their flag remained flying – until Hawkins’ next shot hit their ship. The Spanish flag was immediately lowered – but soon after, in the dead of night, a band of masked men boarded the Spanish ships and set free the Protestant Flemish seamen who the Spanish had captured to use as slaves; they had been chained to the oars in the galley. The Spanish Admiralty blamed Hawkins, failing to see the irony that Hawkins should be rescuing slaves. The incident would damage the prospects for Hawkins’s future trading voyages.

Slaves exposed naked for sale at the end of the vile Triangle. (LC-USZ62-15395)

In October 1567 Hawkins set off on his third slaving voyage, this time with five ships: the

Jesus of Lubeck

, the

Minion

, the

Angel

, the

William and John

and the

Judith

, the last commanded by his young cousin Francis Drake. Again they made their way to the Guinea coast, where they augmented their human cargo by capturing the Portuguese slave ship

Madre de Deus

(Mother of God). Perhaps only a modern reader can appreciate the irony of the names of these god-forsaken vessels.

They headed to South America and while Hawkins was trading, Drake was sent ahead to Rio de la Hacha, where he was fired upon by Spanish forces, who were determined not to trade with these arrogant Englishmen. When Hawkins arrived, his men landed and took the town, selling eighty slaves there before deciding to head for home.

City and port of Vera Cruz, where Hawkins’ crew were tortured to death. (LC-USZ62-107854)