Plymouth (10 page)

Authors: Laura Quigley

Poor Anne Evans was burnt at the stake in Plymouth. (LC-USZ62-5922)

On hearing Carey’s accusations, Anne changed her story. She had, she said, found a packet of rat’s poison in the house and Philippa had encouraged her to put some in Mrs Weeks’ porridge to teach the old lady a lesson. Anne had then seen Philippa brewing the crushed poison into a beer and had told Anne to put some of the beer into the porridge – the same beer that Philippa poured for Mr Weeks. The more Anne talked, the more elaborate her story became.

The questioning continued for weeks, the girls forced to remain in the sordid accommodation of Plymouth gaol, next to the Guildhall. Philippa Evans steadfastly denied any involvement in the murders, but Anne’s story became increasingly wild.

At last the two girls appeared before the Lent Assizes in Exeter. The jury proclaimed them guilty of the murder of Elizabeth Weeks and Mary Pengelly, and the judge refused the girls’ plea for transportation. Philippa Carey was sentenced to be hanged, while poor Anne Evans was to be burned at the stake. Anne’s sentence was rare in Britain. Burning at the stake was more common in Europe, particularly for heretics or witches, but Anne Evans was neither a heretic nor a witch, but something worse, perhaps – a servant who had murdered her mistress. And for that, she had to be made an example of.

The sentence would normally have been carried out in Exeter, but the grieving Mr Weeks, a justice of the peace, was adamant that the girls should be seen to be punished for their crimes in Plymouth. It was agreed that the girls would be taken to Plymouth and executed on the Thursday before Easter, just two weeks later.

Philippa Carey tried to stay the execution by declaring she was pregnant, but the midwives could find no proof of this. The supposed father of the child was not revealed. Carey was later described as a widow, so her husband may have died while she was suffering in Plymouth gaol. He may even have been the murderer: when Philippa was asked to confess her crime, she replied ‘it may be that vile person, my husband, had a hand in it, but he is gone’.

One man who kept a close eye on the proceedings of the trial was John Quick, a non-conformist minister who himself had been repeatedly gaoled for preaching against the established Church. Just after the trial he wrote a book,

Hell Open’d, or the Infernal Sin of Murther Punished, Being a True Relation of the Poysoning of a Whole Family in Plymouth, Whereof Two Died in a Short Time

. He was a devout man, firmly believing in the redemptive powers of confession and adamant that the two girls confess their crimes, for ‘it was as easie going to heaven from the stake and gallows as from their beds; and when their souls were departing from their bodies, God’s holy angels would convey them into Paradise’. But Philippa Carey remained defiant, insisting on her innocence.

![]()

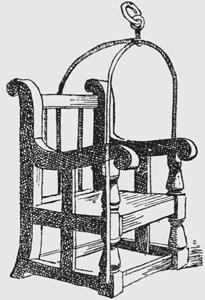

The ducking stool was awarded to Plymouth as part of its incorporation as a town, and was in regular use in the punishment of women. The equipment was set on the edge of Sutton Pool and guilty women would be strapped and girdled into the seat – the ‘cage’ – and then lowered by rope into the filthy, freezing water below. In 1598 Mrs Cook and Mrs Coyt were both ducked for being scolds, and in 1607 Joseph Gubbs was paid to duck another wicked wife. Illegally selling wares directly to the ships was enough to get a woman ducked in 1657 – she would be fined, strapped into the stool and then hauled up three times.

![]()

A typical ducking stool of the era, showing the loop which was used to lower the chair into the water.

As the prisoners were brought from Exeter on horseback, thousands joined the procession at Plymouth. Quick tells us that the nurse exchanged ribald and obscene jests with the spectators.

Quick was gravely concerned for the morality of Plymouth. In the 1670s, Plymouth seemed populated with wicked sinners, undeterred by severe punishments. Malefactors were hanged in chains in public view, or branded and hanged, and the prisons were over-crowded with men and women locked in together in stinking cells.

In 1676 one John Codmore was hanged for admitting twenty-eight offences including horse stealing and the sale of his wife to a miller for £5. He was one of many hangings. As the ministers prayed, the condemned convicts either wept and pleaded for a quick death on the gallows, or angrily cursed the ministers and the spectators as they sang Psalms to strike the devil from the town. Executions were a public display of exorcism. Everywhere he looked, Quick saw sin and debauchery, and he was determined to turn this Sodom of Plymouth into a new Jerusalem – starting with the souls of Anne Evans and Philippa Carey.

The execution was anticipated as a rare spectacle, for there had not been a burning at Plymouth before. While the girls remained in Plymouth gaol, their gaolers were selling tickets to the leering crowd. Quick advised Anne Evans not to fear the fire: she had confessed, and therefore God would carry her through the ordeal; the flames, he said, would hurt her body but not her soul. In contrast, he advised the defiant Carey that she had made a terrible deal with the Devil and would go to hell. Angry with Carey’s refusal to confess, he described her in the most memorable of terms: ‘[her] brow is of brass, she is impudent and hath a whore’s forehead. If there were a very daughter of Hell, this was one in her proper colours.’

As he counselled and admonished the prisoners, a gallows and a stake were being erected on Prince Rock, the highest point of Plymouth, near the Cattewater.

![]()

By today’s standards, the punishments in early Plymouth seem unduly harsh. In the fifteenth century, a thief would be hanged. Women thought to be whores or of ill-repute were whipped, many then exiled from the town. In 1590, Thomas Payne was paid to whip six whores. A woman’s fidelity was paramount, and in the 1540s Joanne Collins brought a suit against John Meyow for apparently forcing her to have sexual relations with him on promise of marriage and then reneging on his promise, leaving her unmarried, with child and in disgrace. Joanne’s fidelity was her main defence: ‘she being an honest maid and replete with the many honest and womanly qualities as well as the gifts of nature as of grace and fortune’.

She then added that he ‘provoked her to consent unto his filthy lust of the flesh... abusing her body so that he hath begotten her with child’ by force of arms, threatening her with a dagger. To avoid a whipping, Joanne had to prove she had been raped at knifepoint.

![]()

On the appointed day, all of Plymouth was on or around Prince Rock: at least 10,000 people were waiting, eager for the spectacle. The mayor, the under-sheriff and the executioner were barely able to make it through the crowd. Anne Evans was carried on a wicker sledge from Plymouth gaol to the stake. She lay curled up on her left side, her Bible under her arm, shocked into immobility as though she was already dead. She was then pinned to the stake by an iron hoop, while Carey was positioned downwind, standing on a ladder beneath the hanging rope. Quick said prayers and the crowd and poor Evans joined in, singing a Psalm. Evans was offered strong drink to support her ‘in her last agonies with Death and conflicts with the Devil’.

A rope was wrapped around Anne Evans’ neck, but the executioner was all for setting the wood alight beneath her before she was strangled. The crowd, in pity, demanded that the rope be tightened first, and the block taken from beneath her feet, and soon she fell, strangled to death. It took a further fifteen minutes before the executioner could get the wood to light and the first smoke blew into the face of Philippa Carey, forced to watch the burning for two hours before she too was executed.

![]()

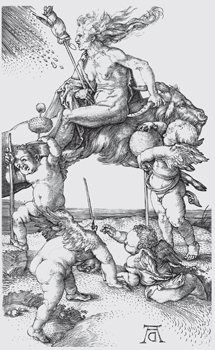

There are very few reports of witchcraft in Plymouth, though Bracken (1931) and Whitfield (1900) were adamant that it was being secretly practised in Plymouth.

Scores of women and men were hanged in Devon in the last half of the seventeenth century, suspected of practising the dark arts. Fear of witches gave the constables the authority to drive any unsavoury characters out of the town, usually accompanied by a beating. In 1801, Peter and Grace Steel were accused of being fortune tellers and committed to the ‘house of correction’. In 1804, Deborah Tanner suspected her neighbour, Ann Raddon, of being a witch – and stuck a pin in her to test her theory. Ann Raddon complained about this, and Deborah was forced by the court to apologise. Plymouth refused to countenance witchcraft in any form – but in the meantime, those wishing to consult with a practising witch just had to cross the Tamar into Cornwall.

![]()

Early engraving of a witch, pictured riding backwards upon a goat. Magical powers could often be detected – well, according to Witch-Finder General Matthew Hopkins, anyway – by a spot upon the body that was impervious to pain. Deborah Tanner was trying to detect this spot when she thrust a pin into Ann Raddon. (LC-USZ62-123495)