Plymouth (2 page)

Authors: Laura Quigley

650-700

THE STONE HOUSE

W

HEN THE SAXONS

invaded the South West of England, sometime in the late seventh century, they discovered a ruined stone house on the shores of Plymouth Sound, on the edges of the salt marshes that once infested that area.

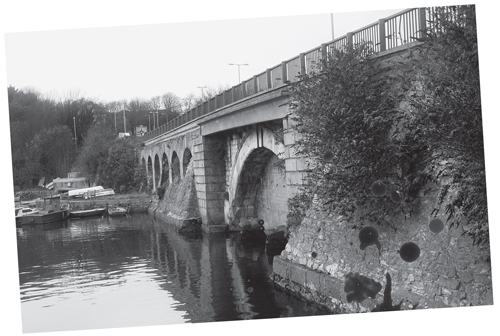

Stonehouse Bridge today, where the Roman remains were found during engineering work.

In 1882 a strange stone building was re-discovered during engineering works to raise Stonehouse Bridge, near Newport Street. The ancient building comprised a series of rectangular chambers or crypts, each containing the burnt remains of human bodies. The stone house was likely to have been a Roman crematorium.

![]()

In

AD

997, Vikings successfully raided Plymouth, stealing precious metals and coin, attacking all who stood in their path. They anchored in Barn Pool, near Mount Edgcumbe, then sailed up the Tamar River systems and ransacked the Anglo-Saxon mint at Lydford, burning, pillaging and slaying. Ordulf’s Minster at Tavistock was burned to the ground before the Vikings made their daring escape. Previously the Vikings had joined the Cornish Celts in the west to attack the Saxon forces in Devon. The victorious Saxons subsequently established the east bank of the Tamar River as the border dividing the Saxons and the Celtic Cornish. The two populations once lived and worked together throughout the south-west peninsula, but the Vikings tore them apart.

![]()

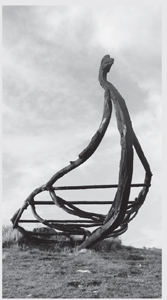

Skeleton of a Viking ship. (Melanie Kuipers, SXC)

Evidence of Roman settlement in Plymouth is sparse. A hoard of Roman coins was found in 1894, probably the pay for soldiers, while small artefacts have been discovered all around the Plymouth Sound, at Plymstock, Mount Batten, Millbay and Sutton Pool, including a small statue of Mercury, the god of trade. What evidence there is suggests a small Roman outpost, administering Celtic tin and copper production. The South West was very muddy back then, and the Romans were renowned for their aversion to mud, so they didn’t venture much past Exeter if they could help it.

Rome fell and the Saxons arrived in Plymouth to discover the strange house made of stone. The Romans built their crematoria like Roman villas – literally a house of the dead built beyond the walls of their settlements. The Saxons found the ruined Roman house of the dead on the edge of the marsh very ominous indeed, a morbid fascination that ultimately led to the founding of the village named Stonehouse on the shores of Plymouth Sound.

![]()

Stonehouse is closely associated with the word Cremyll, with Cremyll Street leading towards Devil’s Point headland, and the opposite headland called Cremyll (sometimes pronounced ‘crimble’, though the origins of the name are obscure).

Cremare

is the Latin for ‘to burn up’; perhaps the grisly crematorium inspired the name?

![]()

![]()

A burial mound from the Bronze Age was discovered in Mount Edgcumbe Country Park, dating back to 1200

BC

, obviously the burial site of someone very important. Bronze mirrors, daggers and coins have been discovered on the opposite headland, at Mount Batten, suggesting a long period of Bronze Age settlement.

![]()

Plymouth from Mount Edgcumbe. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress, LC-DIG-ppmsc-08784)

1348

THE BLACK DEATH AND OTHER AILMENTS

I

N 1066 THE

Normans conquered England and all the Saxon manors around Plymouth changed hands – at the point of a sword. The Norman Barons viciously suppressed a Saxon rebellion, and then established a line of great stone castles along the South West peninsula to control the Saxon population. The Saxons had already established a range of south-facing defences around Plymouth harbour to repel any raids from the sea, extending the previous fortifications of the Britons, the Celts and the Romans. However, the Normans confused the local Saxon lookouts by attacking by land – a cry of ‘they’re behind you!’ might have changed the course of history – and the Normans besieged Exeter before conquering all the lands around Plymouth.

The name Plymouth was then unknown, with Sutton Pool (or South Town Pool) just a small fishing village. The main settlement was then at Plympton, where the Saxons’ Priory governed all tin mining and local administration, and it was probably this ‘plym-town’ that gave the nearby river its name (rather than the other way around).

Observing the substantial wealth of Plympton Priory, the Norman Baron Baldwin de Redvers built his formidable Plympton Castle right next door. His soldiers kept hot oil and coal ready on the castle’s battlements to be hurled down on any rebellious Saxon monks, and so Plymouth fell under the absolute control of the Normans.

Some years later, Baron Baldwin de Redvers made the mistake of supporting Empress Matilda in her battle with her cousin King Stephen over the English throne, and in retaliation King Stephen razed Baldwin de Redvers’ fine castle to the ground. With de Redvers out of the way, another Norman family – the Valletorts, based at Tremarton Castle on the other side of the Tamar – moved in to claim the land around Sutton, which infuriated the monks at Plympton Priory. The Priory’s nearest waterways were silting up with the effluence from tin mining, so the ships chose instead to anchor in Sutton Pool to load their valuable cargoes, and the income to Plympton Priory suffered. Many years were spent arguing with the Valletorts over the growing settlement around Sutton Pool and the influential port that would become Plymouth.