Pediatric Primary Care Case Studies (67 page)

Read Pediatric Primary Care Case Studies Online

Authors: Catherine E. Burns,Beth Richardson,Cpnp Rn Dns Beth Richardson,Margaret Brady

Tags: #Medical, #Health Care Delivery, #Nursing, #Pediatric & Neonatal, #Pediatrics

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. (2006a).

National Health Interview Survey raw data, 2006

. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. (2006b).

Advance data from vital and health statistics. The state of childhood asthma, United States, 1980–2005

. Number 381.

Gore, C., & Custovic, A. (2005). Can we prevent allergy?

Allergy, 59

, 151–161.

Graham, L. M. (2006). Preschool wheeze prognosis: How do we predict outcome?

Paediatric Respiratory Review

, 7(Suppl 1), S115–S116.

Hopp, R. J., Bewtra, A. K., Biven, R., Nair, N. M., & Townley, R. G. (1988). Bronchial reactivity pattern in nonasthmatic parents of asthmatics.

Annals of Allergy, 61

, 184–186.

King, M. E., Mannino, D. M., & Holguin, F. (2004). Risk factors for asthma incidence.

Panminerva Medicine, 46

, 97–110.

Kraft, M. (2000). The role of bacterial infections in asthma.

Clinics in Chest Medicine, 21

, 301–313.

Martin, R. J., Kraft, M., Chu, H. W., Berns, E. A., & Cassell, G. H. (2001). A link between chronic asthma and chronic infection.

Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 107

, 595–601.

Martinati, L. C., & Boner, A. L. (1995). Clinical diagnosis of wheezing in early childhood.

Allergy, 50

(9), 701–710.

McDonald, D. M., Schoeb, T. R., & Lindsey, J. R. (1991). Mycoplasma pulmonis infections cause long-lasting potentiation of neurogenic inflammation in the respiratory tract of the rat.

Journal of Clinical Investigation, 87

, 787–799.

McDonnell, W. F., Abbey, D. E., Nishino, N., & Lebowitz, M. D. (1999). Long-term ambient ozone concentration and the incidence of asthma in non-smoking adults: The AHSMOG study.

Environmental Research, 80

(2 pt 1), 110–121.

National Center for Health Statistics. (2002).

National Health Interview Survey

. Hyattsville, MD: Author.

National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. (2007).

Expert panel report 3: Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma

. Washington, DC: Author.

Sandford, A., Weir, T., & Pare, P. (1996). State of the art: The genetics of asthma.

American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 153

, 1749–1765.

Scirica, C. V., & Celedon, J. C. (2007). Genetics of asthma: Potential implications for reducing asthma disparities.

Chest

, 132(5 Suppl), 700S–781S.

Sibbald, B., & Turner-Warwick M. (1979). Factors influencing the prevalence of asthma among first degree relatives of extrinsic and intrinsic asthmatics.

Thorax, 34

, 332–337.

Simon, P. A., Zeng, Z., Wold, C. M., Haddock, W., & Fielding, J. E. (2003). Prevalence of childhood asthma and associated morbidity in Los Angeles County: Impacts of race/ethnicity and income.

Journal of Asthma, 40

, 535–543.

Smith, L. A., Hatcher-Ross, J. L., Wertheimer, R., & Kahn, R. S. (2005). Rethinking race/ethnicity, income, and childhood asthma: Racial/ethnic disparities concentrated among the very poor.

Public Health Reports, 120

(2), 109–116.

Strachan, D. P. (1989). Hay fever, hygiene, and household size.

British Medical Journal, 299

, 1259–1260.

Strachan, D. P., Butland, B. K., & Anderson H. R. (1996). Incidence and prognosis of asthma and wheezing illness from early childhood to age 33 in a national British cohort.

British Medical Journal, 312

, 1195–1199.

Strachan, D. P., & Cook, D. G. (1998). Parental smoking and childhood asthma: Longitudinal and case control studies.

Thorax, 53

, 204–212.

Weitzman, M., Gortmaker, S., Walker, D. K., & Sobol, A. (1990). Maternal smoking and childhood asthma.

Pediatrics, 85

, 505–511.

Chapter 18

The Overweight Child with High Blood Sugar

Arlene Smaldone

A child may receive a life-altering diagnosis of a chronic health condition at the time of an acute hospitalization. At follow-up, the primary care provider must review the hospitalization course and laboratory data, perform a history and physical examination, consider family preferences for ongoing care and alternative treatment options, and, perhaps, refine a diagnosis. Most important, the primary care provider can be instrumental in assisting children and families to positively adapt to the new demands imposed by the chronic condition and promoting parent/adolescent shared responsibility for care.

Educational Objectives

1. Apply current guidelines for diagnosis and management of type 2 diabetes to an African American teen.

2. Identify common comorbidities of type 2 diabetes and screening guidelines.

3. Apply appropriate laboratory testing guidelines for an adolescent with type 2 diabetes.

4. Understand the need for a team approach in the delivery of care for a child with type 2 diabetes.

5. Consider developmental and sociocultural factors that may impact the diabetes management plan.

Case Presentation and Discussion

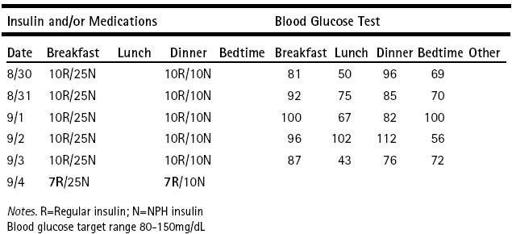

You first meet Mary Smith, a 14-year-old African American female, when she comes to your rural community health center for “follow-up.” Three weeks ago while visiting her aunt in another city during summer vacation, she became ill and was hospitalized for 3 days. She was diagnosed with diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), required intensive care for 2 days, and was told she has diabetes. She was discharged from the hospital on a two injection per day regimen of combined short- and intermediate-acting insulin. During the hospitalization, she and her aunt met with a nutritionist and a diabetes educator. Mary is currently monitoring her blood glucose levels four times per day. She complains of feeling very hungry before lunch and at bedtime. Mary does not bring her blood glucose records but does bring her glucose meter to the visit. Review of blood glucose values stored in the glucometer memory demonstrate readings in the range of 80–100 mg/dL before breakfast and dinner and readings in the range of 60–80 before lunch and at bedtime (

Figure 18-1

).

Figure 18-1 Blood glucose diary highlighting pattern of hypoglycemia before lunch and at bedtime and recommended insulin adjustment.

You obtain a family history and discover that Mary’s maternal grandmother and uncle have type 2 diabetes. Mary’s uncle receives dialysis for diabetes-associated end stage renal disease. Mary has two younger siblings, an 11-year-old brother and a 5-year-old sister.

You ask Mary’s mother to wait in the waiting room while you talk to Mary and complete her physical examination.

What further data do you need to work with Mary and her diabetes diagnosis?

History

Your conversation with Mary reveals the following: Menarche occurred 2 years ago; her menstrual periods are irregular and occur every 2 to 3 months. She denies sexual activity, smoking, or drug use. Mary administers all insulin injections and talks about how hard it is to resist eating “junk food.” She plays softball on a school team 2 days per week but is inactive on other days. She is in the ninth grade and is a “B” student. She has several friends but has not told anyone about her diabetes. She asks you, “Will I always need to take insulin?” You respond by saying that for now, she needs to continue with injectable insulin to control her hyperglycemia, and that you need additional information before you can answer her question.

Physical Examination Findings

You go on to complete her physical examination before deciding on your plan of care for this long-term diagnosis.

Height: 63 inches (50th percentile); weight 150 pounds (90–95th percentile); body mass index (BMI) 26.6 kg/m

2

(90–95th percentile); blood pressure 132/86 (> 95th percentile for age and height) (Frazier & Pruette, 2009; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group, 2004); heart rate 78 beats per minute; respirations

14 per minute; office urinalysis pH 7.0, specific gravity 1.010; glucose, protein, and ketones negative. Mary’s physical examination is positive for the presence of moderate acanthosis nigricans on the back of her neck and at her axillae.

Diabetes: but what type?

Before you can set up the appropriate long-term plan for Mary, you need to have more information about the diabetes diagnosis Mary brings to you. Sometimes it is difficult to distinguish between type 1 and type 2 diabetes in adolescents at the time of diagnosis. Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), although a more common presentation of type 1 diabetes, does not exclude a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes (Gahagan & Silverstein, 2003). In one sample of urban youth with type 2 diabetes, 8% presented in DKA at diagnosis (Zdravkovic, Daneman, & Hamilton, 2004). It is important to differentiate between the types of diabetes because treatment options, education approaches, and screening recommendations will differ. The incidence of type 2 diabetes during childhood and adolescence is rising, particularly among adolescents in minority populations. This increase, largely attributed to the rising rate of obesity in childhood, has long-term implications from a public health perspective.

You need to set up a plan for today’s visit pending more information, so you ask Mary’s mother to authorize release of Mary’s hospital records in order to review her hospital record and laboratory evaluation at the time of diagnosis. Today, you note that Mary’s blood pressure is elevated and that she is having frequent episodes of hypoglycemia before lunch and at bedtime.

Figure 18-1

illustrates the patterns of Mary’s blood glucose values. As you await data that will help to clarify Mary’s type of diabetes, you decide to decrease Mary’s short-acting insulin dose at breakfast and dinner by 10%, and review target blood glucose ranges and identification, as well as treatment of hypoglycemia with Mary and her mother. You also give them a handout from Children’s Hospital and Regional Center, Seattle, Washington, entitled “What Is Low Blood Sugar? Hypoglycemia for Children and Families” (this can be accessed online at

http://cshcn.org/sites/default/files/webfm/file/WhatIsLowBloodSugar-English.pdf

). You also provide information about diabetes for them to give to school personnel (see

Table 18-1

). You ask Mary to return for follow-up in 2 weeks. In the interim, you instruct Mary to continue to monitor her blood glucose level four times a day and to call you if her blood glucose levels are below 80 mg/dL on two consecutive readings or if her blood glucose levels fall below 80 mg/dL more than four times per week.