Pediatric Primary Care Case Studies (66 page)

Read Pediatric Primary Care Case Studies Online

Authors: Catherine E. Burns,Beth Richardson,Cpnp Rn Dns Beth Richardson,Margaret Brady

Tags: #Medical, #Health Care Delivery, #Nursing, #Pediatric & Neonatal, #Pediatrics

You pause for a moment to consider what, if any, diagnostic studies you should do. Based upon a negative history (no complaints of vomiting, heartburn, painful belching, or recurrent pneumonias) and the lack of physical findings (no hoarseness, tenderness, tooth erosion, or masses), you have no evidence that his wheezing is due to gastroesophageal reflux or a tumor. His cardiac examination is normal, making a cardiovascular condition also unlikely. You are comfortable with your diagnosis of asthma. However, James does have a history of multiple episodes of wheezing and no history of having had a chest X-ray which leaves you somewhat uncomfortable. Thus, the healthcare provider may consider obtaining an initial chest radiograph to rule out other pulmonary pathology. Given this child’s history, you decide to order a chest X-ray (PA and lateral), which reveals a normal cardiothymic silhouette, normal orientation of the great vessels, and mild hyperexpansion. Because of the father’s history of dust and pollen allergies, you also order a radioallergosorbent test (RAST) along with a total IgE level.

Making the Diagnosis

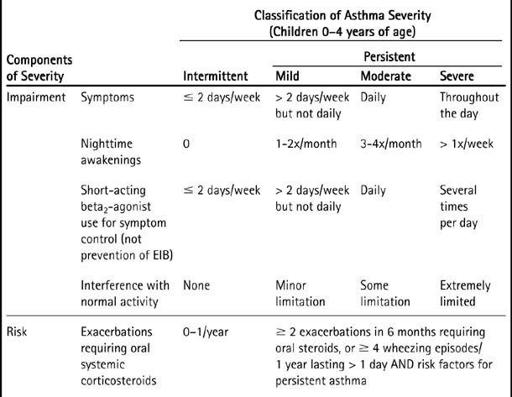

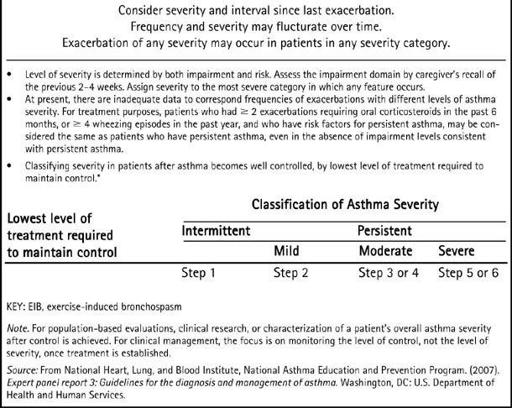

The 2007 guidelines from the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP); National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute; and National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3) are moving away from the initial severity classification to a classification based on disease control. Asthma “severity” refers to the underlying intensity of the disease

before treatment is initiated, and it is important to remember that severity and control are related.

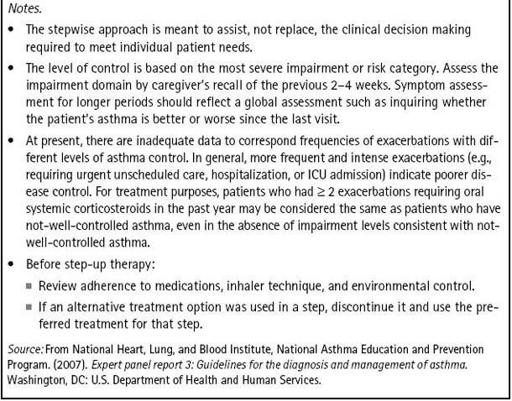

Based on the EPR-3 guidelines, the provider must first determine the severity of the asthma. After the child’s asthma becomes well controlled on medication (plus the elimination of environmental triggers as much as possible), the provider then determines classification based on the lowest level of treatment needed to maintain control. This second classification is made after a period of time in which the provider follows the child. The National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (2007) provides assessment guidelines for the clinician about evaluating components of asthma severity and asthma control (See

Tables 17-2

and

17-3

).

Classification of the Severity of James’ Asthma

Based upon his history, physical examination, and environmental and family risk factors, James was diagnosed with an asthma exacerbation with underlying mild persistent asthma.

Management

Medication Management

Having determined the asthma severity level that James is experiencing based on his history and physical examination findings, you are ready to identify an appropriate medication plan. You prescribe a short burst of oral steroids and an inhaled short acting beta

2

-agonists (SABA) to treat his acute asthma symptoms and this exacerbation. Oral systemic steroids are used to quickly treat the inflammatory response. A SABA provides quick relief of bronchospasm, relaxing airway smooth muscles, which results in a prompt increase in airflow. A spacer is used so that a higher proportion of small, respirable particles are inhaled rather than having particles from the MDI deposited in the oropharynx. This is particularly important for children who receive inhaled medication via MDI devices.

Inhaled corticosteroids are considered long term control medications and are effective agents to block late reactions to allergens and reduce airway hyperresponsiveness. They also act to inhibit the release of key inflammatory agents.

James was started on oral prednisolone (2 mg/kg divided BID for 5 days) and albuterol 5 mg via MDI (2 puffs) with spacer every 4 hours PRN. Based on the NAEPP guidelines, he will start a low-dose inhaled corticosteroid (0.25 mg budesonide BID) as his daily maintenance medication along with a short-acting bronchodilator (5 mg albuterol via MDI [2 puffs] with spacer) as needed.

Control of Environmental Factors and Other Conditions That Can Affect Asthma

EPR-3 describes new evidence for using multiple approaches to limit exposure to allergens and other substances that can worsen asthma; research shows that single steps are rarely sufficient. EPR-3 also expands the section on other common conditions that asthma patients can have and notes that treating chronic problems such as rhinitis and sinusitis, gastroesophageal reflux, overweight or obesity, obstructive sleep apnea, stress, and depression may help improve asthma control.

Table 17–2 Classifying Asthma Severity in Children 0-4 Years of Age Not Currently Taking Long-Term Control Medication

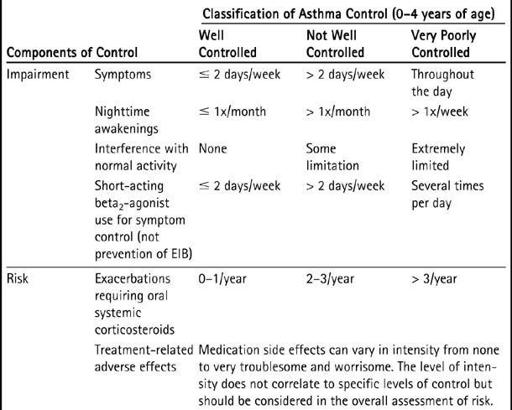

Table 17–3 Assessing Asthma Control and Adjusting Therapy in Children 0-4 Years of Age

What kind of follow-up plan is appropriate for a child with a new asthma management plan?

Follow-up Visit

James returns for a follow-up visit in 4 weeks. According to Mom, he has been sleeping well with no nighttime awakenings and has not had any difficulty keeping up with the other children at daycare.

He continues to take his budesonide as prescribed and after the first week of treatment, James has not needed to use his albuterol. His RAST testing indicated high reactivity to dust mites and ragweed and moderate reactivity to dog epithelium. Total IgE level was 42. (Normal in reference laboratory is < 35.)

Asthma control can be very complicated and should be tailored to the individual’s lifestyle, the individual’s history and risk factors, and daytime and nighttime symptoms; the need for “rescue” medications should be used as the best determinant for adjusting therapy. The history obtained at follow-up visits for patients with asthma is helpful in determining if control is adequate. Some examples of pertinent historical questions include current medications and other therapies, how often a short-acting beta

2

-agonists (SABA) is used, school attendance and performance, and physical activity. You assess that James is well controlled (see

Table 17-3

on p. 262).

Key Points from the Case

1. Asthma is a variable disease that commonly begins in early childhood; healthcare providers must learn to recognize the signs and symptoms of asthma in infants and young children.

2. Along with well-known environmental triggers, genetic factors may play a role in disease severity and individual response to treatment.

3. Establishing a diagnosis of asthma involves thorough history taking and physical examination, as well as the exclusion of other possible causes of wheezing. The history should focus on symptoms (i.e., cough or wheeze), precipitating factors or conditions, and the child’s typical symptom patterns. Additional history should include a history of atopy, family history of asthma, environmental history, and past medical history. The physical exam is generally normal in the absence of an acute exacerbation. Abnormal findings can suggest severe disease, suboptimal control, or associated atopic conditions.

4. When a diagnosis of asthma is established in a child who is not currently on controller medications, asthma severity should be assessed so that appropriate controller therapy can be started. Treatment should be based on the new EPR-3 treatment guidelines and tailored to the individual needs of the patient because responses to treatment often vary. Asthma control is zero or two or fewer times per week of daytime symptoms or need for SABA; zero limitations on daily activities including exercise; zero nocturnal symptoms or awakening due to asthma (think cough in younger patients); normal or near normal lung function results when available; and finally, no exacerbations.

REFERENCES

Akinbami, L., & Schoendorf, K. (2002). Trends in childhood asthma: Prevalence, health care utilization, and mortality.

Pediatrics, 110(2

pt 1), 315–322.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Environmental health. (1997). Environmental tobacco smoke: A hazard to children.

Pediatrics, 99

(4), 539–642.

Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America. (2000).

Cost of asthma: A national study

. Retrieved March 26, 2009, from

http://www.aafa.org/display.cfm?id=6&sub=63

Bush, A. (2007). Diagnosis of asthma in children under five.

Primary Care Respiratory Journal, 1

(1), 7–15.

Busse, W. W., O’Bryne, P. M., & Holgate, S. T. (2006). Asthma pathogenesis. In: N. F. Adkinson Jr, J. W. Yunginger, W. W. Busse, B. S. Bochner, S. T. Holgate, F. E. R. Simons, (Eds.),

Middleton’s allergy: Principles and practice

(6th ed., Chapter 66). St. Louis, MO: Mosby.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2002).

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001–2002 data documentation: Household interview questionnaire

. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.