Paul Revere's Ride (46 page)

Read Paul Revere's Ride Online

Authors: David Hackett Fischer

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #United States, #Historical, #Revolutionary Period (1775-1800), #Art, #Painting, #Techniques

General Gage stopped the admiral from executing his plan, and continued his search for a peaceful solution. He sent a plan of conciliation to Governor Trumbull of Connecticut and came close to negotiating a “cessation of hostilities” with two of Trumbull’s emissaries, until Massachusetts Whigs learned what was happening and put a stop to it. In Boston, Gage refused to impose martial law immediately after the battle, though strongly urged to do so. To prevent bloodshed he persuaded the selectmen to arrange the surrender of all private weapons in the town, in return for a promise that all who wished to leave could do so. He kept his troops inside defensive lines and forbade them to attack the Americans, though many were itching to fight. “We want to get out of this cooped up situation,” Lieutenant Barker wrote in frustration on May 1. “We could now do that I suppose but the General does not seem to want it. There is no guessing what he is at.”

23

While British commanders quarreled among themselves, the Americans went to work with a renewed sense of common purpose. Along the Battle Road they gathered up the wounded and buried the dead. Dedham’s Dr. Nathaniel Ames went to the scene of the fighting. “Dead men and horses strewed along the road above Charlestown and Concord,” he wrote in his diary. In the field, Dr. Ames dressed wounds and “extracted a ball from Israel Everett.”

24

In the town of Lincoln, Mary Hartwell watched with grief as the men of her family “hitched the oxen to the cart and went down below the house and gathered up the dead.” Five British bodies were piled into the cart and carried to Lincoln’s burying ground. She specially remembered “one in a brilliant uniform, whom I supposed to be an officer. His hair was tied up in a cue.”

25

At Menotomy, the dead militiamen from Danvers were heaped on an ox-sled and sent home to their town, while the children looked on. Many years later Joanna Mansfield of Lynn still vividly remembered the terrible image of the American dead piled high on the sled, their legs projecting stiffly over the side as they passed through her village. All of them, she recalled, were wearing heavy stockings of gray homespun.

26

On Lexington Green, the minister’s daughter, eleven-year-old Elizabeth Clarke, watched as the dead were gathered up and laid in plain pine boxes “made of four large boards nailed up.” She wrote long afterward to her niece, “After Pa had prayed, they were put into two large horse carts and took into the graveyard where your grandfather and some of the neighbors had made a large trench as near the woods as possible, and there we followed the bodies of the

first slain,

father and mother, I and the baby. There I stood, and there I saw them let down into the ground. It was a little rainy, but we waited to see them covered up with the clods. And then for fear the British should find them, my father thought some of the men had best cut some pine or oak boughs and spread them on their place of burial so that it looked like a heap of brush.”

27

While these scenes were repeated along the Battle Road, the Whig leaders gathered in Cambridge and began to prepare for the struggle ahead. Once again, Paul Revere was at the center of events. On the morning after the battle he was at the Hastings House in Cambridge, which became the temporary seat of government in Massachusetts. There he was invited to meet with the Committee of Safety, the nearest thing to a functioning executive authority for the province.

28

Rachel Revere remained in Boston, one of Admiral Graves’s female hostages. She was less concerned about her own fate than about the safety of her husband. After the battle he managed to get a message to her, but Rachel continued to worry that he had nothing to live on but the charity of his many friends. She decided to smuggle money to him by Dr. Benjamin Church, who seemed able to pass through British lines with remarkable ease. Somewhere, perhaps from the cash box in the shop, she collected a substantial sum and sent it with a letter of love:

My dear by Doctor Church I send a hundred and twenty-five pounds & beg you will take the best care of yourself & not attempt coming into this towne again & if I have an opportunity of coming or sending out anything or any

of the children I shall do it. Pray keep up your spirits & trust yourself

8c

us in the hands of a good God who will take care of us. Tis all my dependence, for vain is the help of man. Adieu my love. from your

Affectionate R. Revere

The message appears never to have reached its destination. The traitorous Doctor Church delivered even this testament of affection to General Gage, in whose papers it turned up two centuries later. One wonders what happened to the money.

29

In Cambridge, Paul Revere had nothing but the clothes he had worn on his midnight ride. He wrote to Rachel, “I want some linen and stockings very much.” Increasingly filthy and probably smelling more than a little ripe, he continued to attend meetings of the Committee of Safety at Hastings House.

30

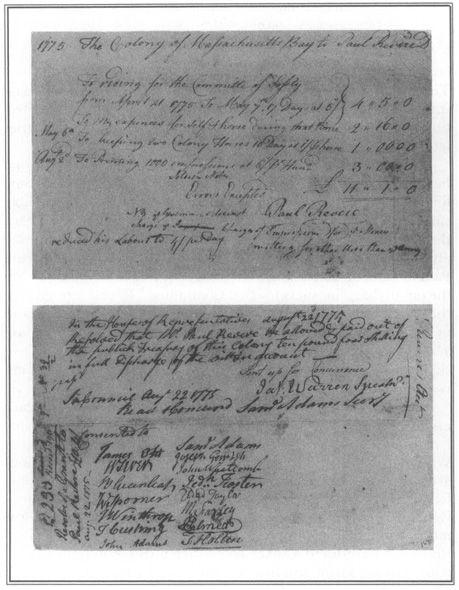

At a session one day after the battle Doctor Warren, perhaps sitting downwind from Paul Revere, turned to him and asked if he might be willing to “do the out of doors business for that Committee.” Revere agreed. For the next three weeks he traveled widely through New England in the service of the committee. Later he submitted an expense account for seventeen days’ service from April 21 to May 7, at five shillings a day, plus “expenses for self and horse” and “keeping two colony horses.”

31

It was common practice in the American Revolution for leaders to be reimbursed for their expenses, and common also for lynx-eyed legislators to pare their accounts to the bone. George Washington himself served without salary during the Revolutionary War, on the understanding that he would be reimbursed only for his expenses. This was thought to be an act of sacrifice, until General Washington’s expense account came in. Then there was much grumbling in Congress. The same thing happened to Paul Revere. A tight-fisted Yankee committee insisted on reducing his daily allowance from five shillings to four, before agreeing to settle his account.

32

No evidence survives to indicate what exactly Paul Revere did for the Committee of Safety in the days after the battle. But in a general way, the activities of the committee are well known. It had much “outdoor work” to be done. The most urgent task was to raise an army. The committee resolved to enlist 8000 men for the siege of Boston, and sent a circular letter to town committees throughout the province.

33

A draft of this document survives, written in Doctor Warren’s flowery style, and heavily revised by the Committee in the meetings that Revere attended. Its impassioned language tells us much about the state of mind among the Whig leaders after the battle:

Paul Revere received no pay or reimbursement for his midnight ride, but like George Washington and many other leaders, he submitted an expense account “for self and horse,” for extended service while “riding for the Committee of Safety” from April 21 to May 7, 1775. The account was approved, but only after his per diem expenses were reduced by one shilling a day, and the bill was signed by sixteen Whig leaders. (Massachusetts Archives)

Gentlemen,—

The barbarous murders committed on our innocent brethren, on Wednesday, the 19th instant, have made it absolutely necessary that we immediately raise an army to defend our wives and children from the butchering hands of the inhuman soldiery, who, incensed at the obstacles they met in their bloody progress, and enraged at being repulsed from the field of slaughter, will, without the least doubt, take the first opportunity in their power to ravage this devoted country with fire and sword. We conjure you, therefore, by all that is dear, by all that is sacred, that you give all assistance possible in forming an army. Our all is at stake. Death and devastation are the instant consequences of delay. Every moment is infinitely precious. An hour lost may deluge your country in blood, and entail perpetual slavery upon the few of your posterity who may survive the carnage. We beg and entreat, as you will answer to your country, to your own consciences, and above all, as you will answer to God himself, that you will hasten and encourage by all possible means the enlistment of men to form the army.…

34

Paul Revere probably carried this document to meetings with town committees throughout the province. The men of New England responded with alacrity, turning out by the thousands to form new regiments which later became the beginning of the Continental Line.

The next “out of doors” job was to supply this army, the largest that New England had ever seen. Some “carcasses of beef and pork, prepared for the Boston market” were found in the hamlet called Little Cambridge. A supply of ship’s biscuit, baked for the Royal Navy, was discovered in Roxbury. The kitchen of Harvard College was converted to a mess hall, and the militia were fed by a brilliantly improvised supply service. The army was successfully maintained in the field, but then another problem arose. Within weeks an epidemic (or polydemic) that was collectively called the Camp Fever broke out among the New England troops, and spread rapidly through the general population. The Camp Fever took a horrific toll. Rates of mortality surged to very high levels in many New England towns, spreading outward from the communities between Concord and Boston.

35

The most important part of the committee’s “out of doors work” was to rally popular support for the Whig cause, in the face of these many troubles. Within a few hours of the first shot, it began to fight the second battle of Lexington and Concord—a

struggle for what that generation was the first to call “public opinion.”

36

The Whig leaders in New England had none of our modern ideas about image-mongering or public relations, and would have felt nothing but contempt for our dogmas about the relativity of truth. But long experience of provincial politics had given them a healthy respect for popular opinion, and they were absolutely certain that truth was on their side. With evangelical fervor they worked to spread what Doctor Warren called “an early, true and authentick account of this inhuman proceeding.”

37

The news of the battle was already racing through America as fast as galloping horses could carry it. A citizen of Lexington wrote that the report of the fighting “was spreading in every direction with the rapidity of a whirlwind.” It was said that on April 19 Concord’s Reuben Brown rode “more than 100 miles on horseback to spread the alarming news of the massacre at Lexington. This process of communication was not left to chance. From the start, the Committee of Safety worked actively to spread the news, and even to shape it according to their beliefs.

38

As early as ten o’clock on the morning of April 19, when the Regulars had barely arrived in Concord, the committee sent out postriders with reports of the the first shots in Lexington. One of these hasty dispatches survives. It summarized what was known at that early hour, and was signed by Paul Revere’s friend Joseph Palmer “for the committee.” A postscript added that “the bearer Mr. Israel Bissel is charged to alarm the country quite to Connecticut & all persons are desired to furnish him with fresh horses as they may be needed.”

39

Israel Bissell, twenty-three years old, of East Windsor, Connecticut, was a professional postrider who regularly traveled the roads between Boston and New York. On the morning of April 19, Bissell was in Watertown, ten miles west of Boston. The Committee of Safety recruited him to carry an early report of the fighting at Lexington. He left about ten o’clock, and galloped west on the Boston Post Road, spreading his news to every town along the way. According to legend, Bissell reached Worcester about noon (more likely a little later), shouting, “To Arms! To Arms! The War has begun!” So hard had he ridden that as he approached Worcester’s meetinghouse his horse fell dead of exhaustion. The men of Worcester remounted him and he galloped on, carrying his message “quite to Connecticut,” as the committee had asked.

40

Bissell made rapid progress on the road. He was in the Connecticut town of Brooklyn by 11 o’clock on the morning of April

20, Norwich by 4 o’clock in the afternoon, and New London by 7 o’clock that evening. From New London, the news traveled west on Long Island Sound. It arrived in New Haven (150 miles from Boston) by noon on the 21st, and New York City (225 miles) by 4 p.m. on the 23rd. Another messenger continued through the night from New York to Philadelphia, and arrived at 9 o’clock in the morning of the 24th—ninety miles in seventeen hours. Baltimore heard the news by April 26, Williamsburg by the 28th, New Bern by May 3, and Charleston by May 9. In the second week of May, the first reports were carried across the mountains to the Ohio Valley. When news of the fighting reached a party of hunters in Kentucky, they called their campsite Lexington. It is now the city of the same name.

41