Paul Revere's Ride (42 page)

Read Paul Revere's Ride Online

Authors: David Hackett Fischer

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #United States, #Historical, #Revolutionary Period (1775-1800), #Art, #Painting, #Techniques

Two miles beyond Menotomy, the marching men began to hear the rattle of musketry in the distance. As they approached the village of Lexington the sounds of battle suddenly increased. Percy ordered his brigade to deploy on high ground half a mile east of Lexington Green, near a tavern owned by Sergeant William Munroe. The 4th was sent to the northern side of the road, and the 23rd to the south. The brigade rapidly formed into a line of battle on the hills of Lexington, with commanding views of the countryside. The Royal Artillery unlimbered its two guns on high ground and emplaced them with long fields of plunging fire along the road to the west.

Suddenly, beyond the village, the red uniforms of Colonel Smith’s men came into view. The men of the brigade were shocked

by the scene that unfolded before their eyes. The grenadiers and light infantry were less a marching column than a running mob, pursued by a cloud of angry countrymen on their flanks and rear. A full regiment of New England militia appeared in close formation behind the Regulars. At extreme range, Percy ordered his artillery to open fire. The cannon balls screamed through the air and the militia instantly dispersed, running for cover from a weapon they had not faced before.

The grenadiers and light infantry of Smith’s shattered force ran up to Percy’s line, and dropped exhausted to the earth. Behind them, the New England men also went to ground and began sniping at the brigade from long range. Their fire did little damage, but goaded the Royal Welch Fusiliers on Percy’s left to break ranks and charge forward without orders. A British officer wrote, “Revenge had so fully possessed the breasts of the soldiers that the battalions broke, regardless of every order, to pursue the affrighted runaways. They were, however, formed again, tho’ with some difficulty.” Percy regained control of his troops, but he was beginning to have the same problems of discipline that had dogged Smith and Pitcairn. He made a point of moving among his men with an air of calm and competence.

29

To keep the New England militia at bay, the British commander sent forward a screen of his own skirmishers. He also ordered his men to set fire to three houses that offered cover to marksmen. As the buildings began to burn, a pall of dark smoke rose over the scene. The firing slackened, and then nearly ceased for half an hour, while the New England regiments rested on one side of the village, and the British brigade remained on the other. Behind the line of Percy’s infantry, the Munroe Tavern became a hospital for the many British wounded. Surgeon’s Mate Simms of the 43rd Foot worked among them, digging the soft lead musket balls from shattered bone and torn flesh.

Percy called his officers together in the Munroe Tavern and considered his position. He had no idea that so many men were in the field against him. Later he wrote to a friend that he was amazed to find “the rebels were in great numbers, the whole country having collected for twenty miles around.” Not having known the magnitude of his task, Percy had left Boston with no reserves of ammunition for his infantry beyond the 36 cartridges that each man carried in his kit. The artillery had only a few rounds in side boxes on the guns. The senior gunner in the garrison had strongly advised the brigade to bring an ammunition wagon, but Percy

thought that it would slow his progress, and said that “he did not imagine there would be any occasion for more than there was in the side boxes.”

30

After the brigade had marched, Gage himself intervened, and sent two ammunition wagons with an escort of one officer and thirteen men. This little convoy was intercepted on the road by a party of elderly New England men from the alarm lists, who were exempt from service with the militia by reason of their age. These gray-headed soldiers did not make a formidable appearance, but they were hardened veterans who made up in experience what they lacked in youth, and were brilliantly led by David Lamson, described as a “mulatto” in the records.

With patience and skill these men laid a cunning ambush for the British ammunition wagons, waited until they approached, and demanded their surrender. The British drivers were not impressed by these superannuated warriors, and responded by whipping their teams forward. The old men opened fire. With careful

economy of effort, they systematically shot the lead horses in their traces, killed two sergeants, and wounded the officer in command.

31

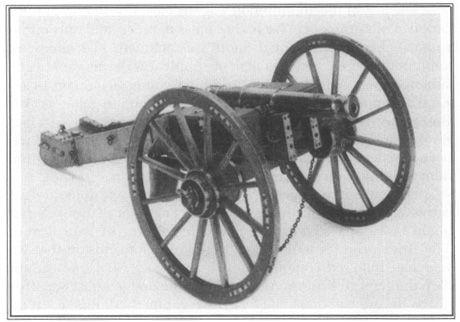

Lord Percy’s brigade marched with two of these six-pounder field guns. They fired a solid iron ball, approximately three inches in diameter. Their presence forced a change in American tactics during the afternoon. Percy refused to take an ammunition wagon with him; the gunners had only the rounds in the small side boxes that are visible between the wheel and barrel. (Museum of Our National Heritage, Lexington)

The surviving British soldiers took another look at these old men, and fled for their lives. They ran down the road, threw their weapons into a pond, and starting running again. They came upon an old woman named Mother Batherick, so impoverished that she was digging a few weeds from a vacant field for something green to eat. The panic-stricken British troops surrendered to her, and begged her protection. She led them to the house of militia captain Ephraim Frost.

32

Mother Batherick may have been poor in material things, but she was rich in the spirit. As she delivered her captives to Captain Frost, she told them, “If you ever live to get back, you tell King George that an old woman took six of his grenadiers prisoner.” Afterward, English critics of Lord North’s ministry used this episode to teach a lesson in political arithmetic: “If one old Yankee woman can take six grenadiers, how many soldiers will it require to conquer America?”

33

The loss of the ammunition wagons gave Lord Percy another problem of arithmetic. “We had 15 miles to retire, and only our 36 rounds,” he wrote. Colonel Smith’s detachment had almost no ammunition at all. The problem of supply was desperate.

34

Percy summoned an aide-de-camp, a dashing young lieutenant of the King’s Own named Harry Rooke, and asked him to gallop back to Boston with an urgent message for the commander in chief. Rooke was ordered to report that Colonel Smith’s command had been rescued, but that the brigade would have to fight its way home, and that further reinforcement might be necessary.

The gallant young officer set off on a hazardous journey across many miles of hostile territory. The saga of Rooke’s ride might be compared with the midnight journey of Paul Revere. The British courier took the same route back to Boston that Revere had followed coming out—Lexington to Charlestown, and then the ferry to Boston. Along the way he dodged hostile patrols just as Revere had done, but by a different method. Rooke left the road, jumping walls and brooks in a wild cross-country gallop. Not knowing the ground, which was very soft in April, he took twice as long to cover the same distance as Revere had done, and did not reach Boston until 4 o’clock in the afternoon, too late to influence the course of events.

35

Even if Rooke had arrived sooner, there was little that General

Gage could have done. Half of his effectives were already in the field. His other regiments were needed to hold Boston against its own inhabitants. Gage ordered his small garrison to remain under arms in barracks, ready for a rising of the population. He asked the navy to send two small armed vessels up the Charles River to cover the bridge at Cambridge. Otherwise, the commander in chief could only sit and wait in suspense for the outcome of events that he had set in motion.

While Gage waited in Boston, Percy was busily reorganizing his forces in Lexington for the long march home. He handled his command differently from Colonel Smith. A larger force was at his disposal, between 1800 and 1900 men, counting the survivors of the Concord expedition.

36

For the march back to Boston, Percy decided not to deploy his men in a single road-bound formation, but to distribute them in three columns, with a strong advanced party and a powerful rear guard. Together its interlocking units made something like a mobile British square. Later he wrote that “very strong flanking parties” were “absolutely necessary, as there was not a stone wall, though before in appearance evacuated, from whence the rebels did not fire upon us.”

37

Percy expected that the pressure would be comparatively weak against the front of his column, but strong on his flanks, and strongest at his rear. He arranged his forces on that assumption. At the front of the formation he placed a small vanguard of fifty men whose task was to clear the road ahead. Behind them came the surviving light infantry of Smith’s command, then the grenadiers, a convoy of carriages bearing wounded officers, and ten or twelve prisoners “taken in arms,” several of whom would be killed by “friendly fire” on the march.

38

To protect his right flank, Percy ordered five companies of the King’s Own to march overland on high ground south of the road. On his exposed left flank, he sent a strong force of the 47th to the north side of the road. For his rear guard he selected the Royal Welch Fusiliers. Supporting the Fusiliers was the artillery. The Marines were his reserve, in a position to reinforce any side of the formation that might be threatened. Percy was prepared to fight in any direction, and could move his guns to the front or rear as need be. His deployment gave him the tactical advantage of interior lines. He could shift his reserves from one side to another more speedily than the Americans could move around the outside of the formation.

39

Percy also made a change in march discipline. Colonel Smith,

despite his reputation for lethargy, had driven his column so rapidly from Concord to Lexington that the flankers could not keep up. Percy decided to march more deliberately, and carefully regulated his pace, so that his flanking parties could keep abreast of the central column as they picked their way over unfamiliar ground. He also gave his men a long rest in Lexington, and planned another stop at Cambridge, halfway home.

40

The terrain posed special problems, but also gave him an opportunity. In Menotomy a rocky ridge ran three miles along the south shoulder of the road, rising as high as 100 feet. Percy’s right flanking column was ordered to secure the ridge; if they could do so, the south side of the formation was protected. To the north of the road were open fields and pastures. Further east the country became more thickly settled, so much so that Lieutenant Evelyn called it “a continued village” from the Lexington line to Boston. The advance guard was ordered to clear the houses close by the highway. Percy’s deliberate pace was designed to leave time for that work.

While Percy reorganized his force, the American commanders were busy with their own arrangements. The regiments that had fought Smith’s column had reached Lexington in some disorder. One regiment had been broken by Percy’s artillery. The others had become somewhat intermingled after the morning’s long pursuit. More companies were arriving from every direction. So well had the midnight riders done their work that elements of twelve New England regiments were in the field by early afternoon. Four of them were the Middlesex regiments (commanded by Colonels Barrett, Bridge, Green, and Pierce) that had fought at Concord. These units were now at full strength, perhaps more than full strength, with their many volunteers. Four other regiments (Colonels Davis, Gardner, Greaton, and Prescott) were at half strength, but rapidly increasing as other companies appeared. Four more regiments were just beginning to arrive from Essex and Norfolk Counties (Colonels Fry, Johnson, Robinson, and Pickering). In addition to these twelve, another eight regiments were gathering in Worcester County to the west. Altogether, no fewer than forty-seven regiments would muster throughout New England that day, perhaps as many as fifty-five. So rapid was their mobilization that several British officers believed they must have assembled several days before.

At Lexington, a general of Massachusetts militia assumed command. He was Brigadier William Heath, a gentleman farmer

from Roxbury, then a beautiful green country town next to Boston. General Heath did not make a martial appearance. He looked the image of the contented country squire that he was—thirty-eight years old, fat, bald, jolly, affable. Sometimes he could be a little pompous; in his autobiography he always referred to himself as “our general.” But he was much beloved by those who knew him well.

41

Most of Heath’s soldiering had been done on militia training days with Boston’s Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company. He had not been in battle before, and had never commanded a large force in the field. But behind his country manner was a Yankee brain of high acuity. As early as 1770, William Heath had become convinced that the people of New England might be forced to fight in defense of their ancestral ways. He began to write for the local gazettes, publishing essays signed “a military countryman,” which urged his neighbors to prepare for the test that lay ahead.

In Boston, William Heath haunted Henry Knox’s bookstore, with its large stock of works on military subjects. By day he studied the Regulars at their drill on the Common. By night he toiled over his books in his Roxbury farmhouse, and made a serious study of war as he thought it might develop in America.

42